Introduction

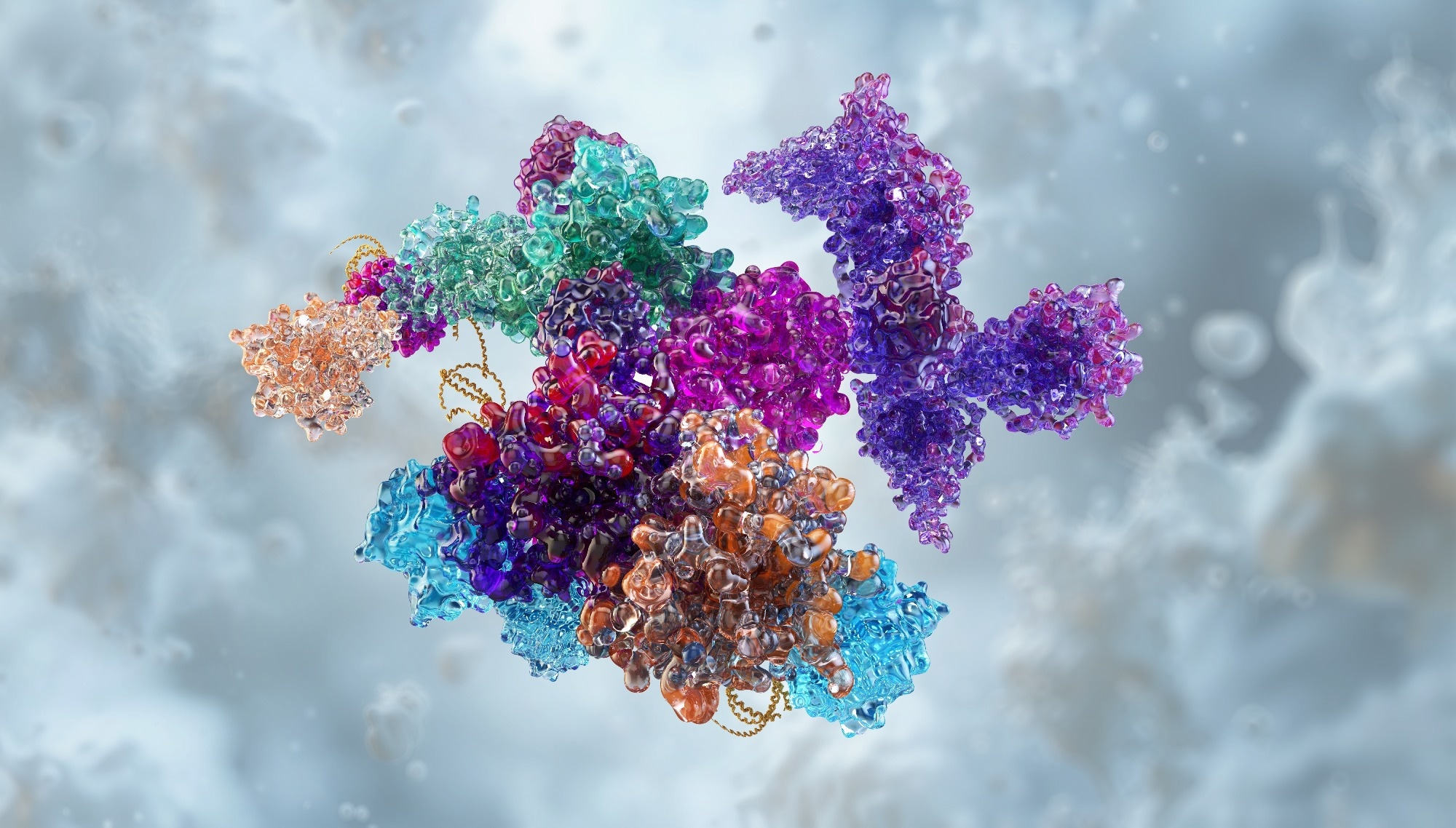

What Is the Spliceosome?

Retroelements and Mobile Genetic Elements

The Retroelement Origin Hypothesis

Evidence Supporting a Retroevolutionary Origin

Implications for Eukaryotic Genome Evolution

Alternative Views and Open Questions

Conclusions

References

Further Reading

What if the defining machinery of eukaryotic life began as a genomic parasite, and its domestication unlocked the regulatory power that shapes complex organisms today?

Image credit: Corona Borealis Studio/Shutterstock.com

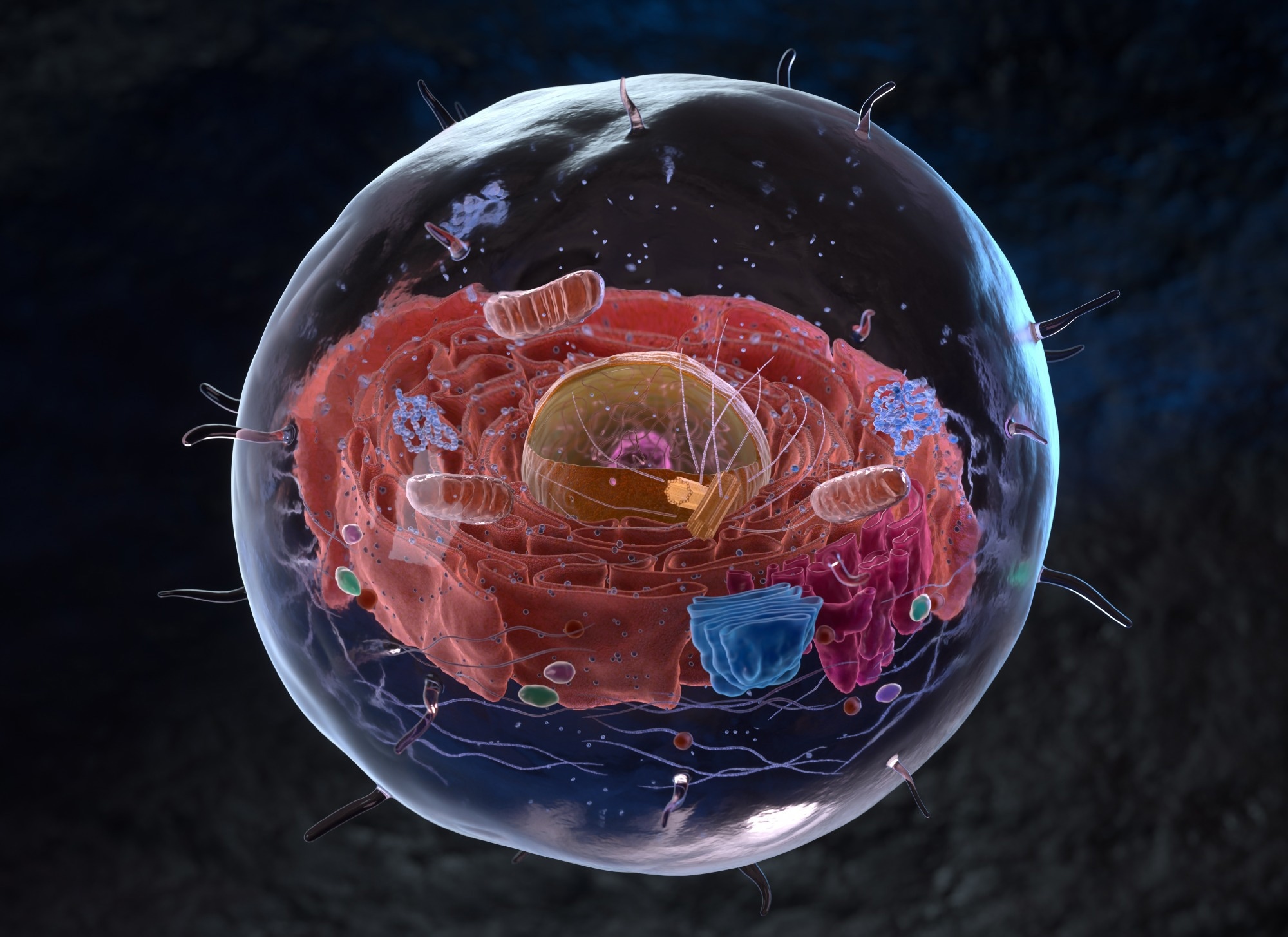

Image credit: Corona Borealis Studio/Shutterstock.com

The eukaryotic spliceosome is a multi-megadalton ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found in eukaryotic nuclei that catalyzes the removal of introns (non-coding regions) from pre-mRNA and splices exons to form mature mRNA (messenger RNA).

Its emergence is now recognized as one of the most pivotal events in eukaryogenesis, coinciding with the transition from prokaryotic to eukaryotic cellular organization.

Researchers currently favor the “retroelement hypothesis,” which assumes that spliceosomal introns and core spliceosomal components evolved from ancestral group II self-splicing introns that invaded the proto-eukaryotic genome during early eukaryogenesis.1,7

This article collates the latest scientific literature on this hypothesis to illustrate how molecular invaders were repurposed to facilitate alternative splicing and proteomic diversification. It synthesizes structural, phylogenetic, and mechanistic evidence, including comparative analyses of group II introns and the spliceosomal catalytic core, and recent evolutionary reconstructions of the spliceosome in the Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestor (LECA).2,3

Introduction

The discovery of “split genes” in 1977 challenged the longstanding linear model of genetic information by revealing that coding exons are interrupted by non-coding introns. This finding initiated decades of investigation into the origin and functional significance of spliceosomal introns.4

Modern consensus supports a model in which spliceosomal introns arose during eukaryogenesis from group II self-splicing introns, most likely introduced via the α-proteobacterial ancestor of mitochondria.1,7

Several evolutionary reconstructions suggest that intron proliferation preceded or coincided with the emergence of a complex spliceosome, indicating that intron spread was an early and transformative event in proto-eukaryotic genomes.3

What Is the Spliceosome?

The spliceosome is a dynamic assembly comprising five small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and over 100 associated proteins in its core machinery, with expanded proteomes in higher eukaryotes. This collective machinery edits the vast majority of multi-exon genes in humans and enables alternative splicing, whereby a single gene can generate multiple protein isoforms.3,5,9

Spliceosome assembly follows a highly ordered pathway: U1 recognizes the 5′ splice site, U2 binds the branch point, and the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP joins to form the pre-catalytic spliceosome. Catalytic activation involves extensive RNA rearrangements in which U6 pairs with U2 to form the catalytic core.5

Direct experimental evidence demonstrates that U6 snRNA coordinates divalent metal ions that catalyze both transesterification reactions, confirming that the spliceosome is an RNA-based metalloenzyme.1

RNA Splicing

Video credit: DNALearningCenter/Youtube.com

Retroelements and Mobile Genetic Elements

Retroelements are mobile genetic elements that replicate via an RNA intermediate, which is converted into DNA by reverse transcriptase. They comprise approximately 45% of mammalian genomes.2

Group II introns are self-splicing ribozymes that encode a multifunctional maturase protein containing reverse transcriptase and endonuclease domains. They are capable of retrohoming and target-primed reverse transcription, enabling insertion into DNA sites.2

The Retroelement Origin Hypothesis

This hypothesis proposes that the spliceosome evolved through fragmentation and functional redistribution of ancestral group II introns. Catalytic RNA domains are proposed to have evolved into trans-acting snRNAs, while intron-encoded proteins gave rise to core spliceosomal proteins.1,3

Phylogenetic analyses indicate that at least 145 spliceosomal proteins were already present in LECA, suggesting rapid expansion through gene duplication and recruitment following initial intron invasion.3

Evidence Supporting a Retroevolutionary Origin

High-resolution cryo-electron microscopy has revealed structural parallels between spliceosomal active sites and group II introns. Both systems utilize a two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism and share homologous RNA architectural motifs.1,2

Structures of group II intron reverse-splicing complexes reveal dynamic movement of domain VI during branch-site exchange, closely paralleling spliceosomal branch-helix rearrangements.2

The largest spliceosomal protein, Prp8 (PRPF8), exhibits structural homology to group II intron maturases, including reverse transcriptase-like domains that envelop the catalytic RNA core.3

Implications for Eukaryotic Genome Evolution

Comparative genomic analyses indicate that LECA possessed an intron-rich genome and a complex spliceosome. Subsequent evolution involved lineage-specific intron loss and gain.3,4

The invasion of introns may have driven the emergence of defining eukaryotic features, including nuclear compartmentalization and separation of transcription from translation.7 Alternative splicing later expanded regulatory and proteomic complexity in multicellular lineages, contributing to tissue-specific expression patterns and phenotypic diversification.9

ImagIma Image credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

Alternative Views and Open Questions

Although the retroelement hypothesis is strongly supported, questions remain regarding the precise timing and cellular context of intron invasion. Some models emphasize mitochondrial origin, whereas others consider contributions from archaea during early symbiogenesis.4,7

Additionally, spliceosomal catalytic steps are reversible under experimental conditions, further underscoring mechanistic continuity with group II introns.5

Conclusions

The spliceosome’s evolution from ancestral retroelements represents a striking example of molecular exaptation. Structural, biochemical, and phylogenetic evidence converges on a shared evolutionary origin between group II introns and the spliceosome.1–3

Understanding these origins not only clarifies a central event in eukaryogenesis but also informs modern biomedical research, as defects in splicing underlie numerous human diseases and are increasingly targeted by RNA-based therapeutics.9

References

- Koonin, E. V. (2006). The origin of introns and their role in eukaryogenesis: a compromise solution to the introns-early versus introns-late debate? Biology Direct, 1(1), 22. DOI:10.1186/1745-6150-1-22, https://biologydirect.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6150-1-22

- Irimia, M., & Roy, S. W. (2014). Origin of Spliceosomal Introns and Alternative Splicing. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 6(6), a016071–a016071. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a016071, https://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/6/6/a016071

- Will, C. L., & Luhrmann, R. (2010). Spliceosome Structure and Function. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 3(7), a003707–a003707. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a003707, https://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/3/7/a003707

- Parker, M. T., Fica, S. M., & Simpson, G. G. (2025). RNA splicing: a split consensus reveals two major 5′ splice site classes. Open Biology, 15(1), 240293. DOI:10.1098/rsob.240293, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsob.240293

- Haack, D. B., et al. (2019). Cryo-EM Structures of a Group II Intron Reverse Splicing into DNA. Cell, 178(3), 612–623.e12. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.035, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009286741930738X

- Fica, S. M., et al. (2013). RNA catalyses nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. Nature, 503(7475), 229–234. DOI:10.1038/nature12734, https://www.nature.com/articles/nature12734

- Hunter, C. E., & Xing, Y. (2026). The splice of life: how alternative splicing shapes regulatory and phenotypic evolution. The EMBO Journal. DOI:10.1038/s44318-025-00666-z, https://www.nature.com/articles/s44318-025-00666-z

- Vosseberg, J., Stolker, D., von der Dunk, S. H. A., & Snel, B. (2023). Integrating Phylogenetics With Intron Positions Illuminates the Origin of the Complex Spliceosome. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 40(1), msad011. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msad011, https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/40/1/msad011/6985000

- Soni, K., et al. (2025). Structures of aberrant spliceosome intermediates on their way to disassembly. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 32(5), 914–925. DOI:10.1038/s41594-024-01480-7, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41594-024-01480-7

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 16, 2026