Stem cells are a hot new area of intensive research in almost every field of medical science. These cells are characterized by their property of self-renewal and ability to differentiate into many different types of cells. They have long been thought to stimulate tissue repair and regeneration by differentiating into the native tissue cells that were injured in the given organ or tissue.

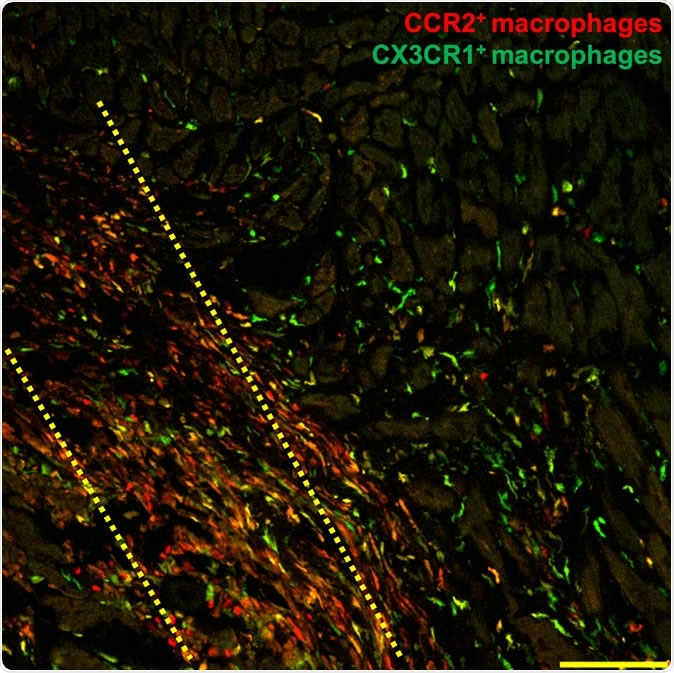

In this microscopic histology image, macrophage immune cells (shown in red and green) flock to the injured region of a damaged mouse heart three days after researchers injected adult heart stem cells within the yellow dotted area. Researchers report Nov. 27 in Nature that stem cell therapy helps hearts recover from heart attack by triggering an innate immune response that alters cell activity around the injured area so that it heals with a more optimized scar and improved contractile properties.

How it happens

Stem cells cause inflammation which is due to macrophage activation. Macrophages are the early warning system of the immune response. They tell the body when stem cells are seen where they are normally absent, in this case. The resulting inflammation causes secondary wound healing that ends in a slight improvement in heart function after a heart attack. The CCR2+ and CX3CR1+ macrophages cause acute inflammation.

The macrophages, along with other nonspecific immune cells, are part of the innate immune response which is the first to react to an antigen or invader. Once this response sets in, the cells around the injured area begin to show a new pattern and level of activity. This eventually causes the scar that is forming to become healthier, resulting in better contractility of the heart tissue in the damaged part.

The study

Earlier research in 2014 by the same team, published in the same journal, provided the basis for the current study. In the prior study, the scientists injected c-kit positive stem cells into the damaged heart. They expected that these cells would replace cardiomyocytes – but it did not happen. This made the researchers ask how actually stem cell therapy worked. To answer this question, they designed a new way of looking at stem cells used as treatment.

They used 2 commonly used types of heart stem cells, namely, mononuclear cells from the bone marrow and cardiac progenitor cells. They looked at the data they had on these cells, testing it and revalidating it, under several different conditions. They were surprised to see that the heart grew stronger if either of the two stem cells were injected, but also if dead stem cells or an inert chemical called zymosan was injected. Zymosan is chemically inert but can provoke innate immunity.

The results

The researchers found that whatever injection was used, the acute sterile immune response that set in caused a difference in the formation of the connective tissue that makes up the extracellular matrix, an important component of the extracellular environment. As a result, the border zone extracellular matrix is reduced. In addition, this inflammation also improved the scar’s mechanical strength. Cardiac fibroblasts became more active. This was observed because “injected hearts produced a significantly greater change in passive force over increasing stretch, a profile that was more like uninjured hearts.”

To achieve this healing the chemical or stem cells must be injected straight into the heart, right around the damaged area. In most cases of previous stem cell research for ischemic heart damage, the injections have been into the circulation, citing patient safety. This could be the reason why so many trials have shown inconsistent results – they were badly designed. Researcher Jeffery Molkentin sums it up: “Our results show that the injected material has to go directly into the heart tissue flanking the infarct region. This is where the healing is occurring and where the macrophages can work their magic.”

And in the case of zymosan, they were interested to note that the beneficial effect produced by injecting this chemical into the damaged area was a little greater and lasted a little longer than when stem cells (dead or alive) were used.

Implications

The researchers say, “The implications of our study are very straight forward and present important new evidence about an unsettled debate in the field of cardiovascular medicine.” They plan to find new and better ways to harness this healing potential of these stem cells and molecules, or even the macrophages themselves. For instance, looking at the intense inflammation triggered by the injection of any of the three agents, the team would like to test the possibility of polarizing macrophages, or forming a biological queue of macrophages that will be able only to heal – thus exploiting the healing resources of this immune cell type.

If they succeed, it could change the way heart disease is treated in the future.

Journal reference:

Vagnozzi, R.J., Maillet, M., Sargent, M.A. et al. An acute immune response underlies the benefit of cardiac stem-cell therapy. Nature (2019) doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1802-2, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1802-2