Scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, have reported, in the journal Cell Reports, the mechanism of how the very early precursor or stem cells which eventually give rise to the germ cells, eggs and sperm, are formed over the course of development. This could help create eggs and sperms under laboratory conditions to help infertile people who don’t have sperms, or eggs, for instance.

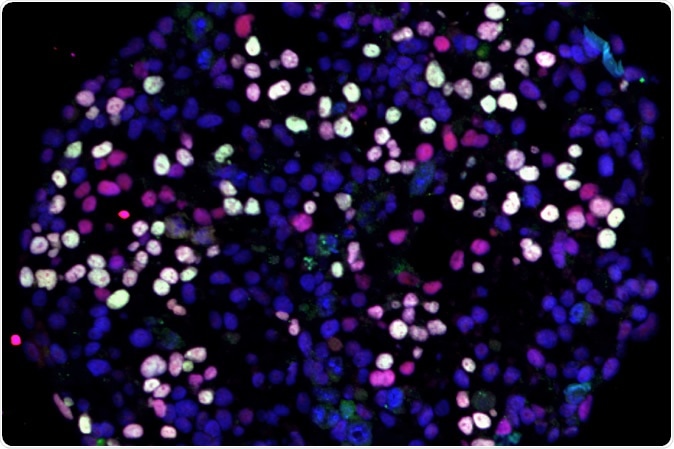

UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center/Cell Reports - Differentiating human pluripotent stem cells (blue) turning into human germ cells (pink and white).

Infertility is a problem for 1 in 10 of the population in the US, and shows an increasing trend over the last few decades because of the later time of first pregnancy. In many of these cases, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and more advanced techniques like intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are successfully used to begin a pregnancy. In IVF, the male and female germ cells are joined outside the body and the resulting conceptus is later inserted back into the uterus. With ICSI, the sperm nucleus is injected directly into the egg cell.

However, both of these techniques require sperm and eggs to be present. When it comes to people who lack these germ cells, other therapies must be looked for. The lack of sperm or eggs could be a result of genetic abnormalities, chemotherapy or radiation, or sometimes unknown causes.

One option is to use donor eggs or sperm, or both. However, as researcher Amander Clark says, “With donated eggs and sperm, the child is not genetically related to one or both parents. What we want to do is use stem cells to be able to generate germ cells outside the human body so that this kind of infertility can be overcome.”

The beginning

All embryos develop from a set of undifferentiated cells are present that is capable of developing in many different directions to make almost any kind of cell in the body. These are the pluripotent stem cells, the cells that can also give rise to sperms and eggs.

Scientists have already discovered how to make cells very similar to these from already differentiated adult skin or blood cells, by reversing the developmental timetable and un-differentiating them. These are called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

The process

The current study made use of technology to measure the genes that were active in over 100,000 embryonic stem cells and iPSCs as they gave rise to sperm and egg cells. This huge amount of information was then analyzed, using newly developed algorithms from their colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to discern the pattern of development.

The scientists were thus able to come up with a high-definition picture of the process by which germ cells are formed. The first step occurred at 24-48 hours, when the stem cells begin to differentiate into the different types of cells that continue to develop into all the distinctive and highly specialized cells of the adult human body.

At the 12th day after fertilization, around the time of implantation but before the earliest formation of embryonic parts like the primitive streak or the gastrula, it is possible to recognize the earliest stem cells that are differentiating into the germ cell production line, called the human primordial germ cells (hPGCs). At this point the hPGC-like cells (hPGCLCs) are specified, or set apart, by a change in their gene expression towards a transitional state. At this point they share the characteristics of the pre-implantation stem cell as well as the post-implantation embryonic stem cell, which is described as naïve and primed, respectively. They then turn into the pathway to become germ cell progenitors, by the regulation of the sex-determining chromosome area SOX17 that is responsible for hPGCLC specification.

At this point, the hPGCLCs can no longer differentiate into somatic cells – this is called crossing Weismann’s barrier, after the legendary German biologist who proposed the existence of the hereditary factor within germ cells, today known to be DNA. This is the key point in achieving the in vitro production of gametes, or sex cells (eggs and sperms).

Implications

In the current experiment, the primed hPGCLCs are turned back to become transitional germinal pluripotent cells and thus begin to differentiate into germ cells. The researchers now know when to intervene so that they can maximize the number of germ cells formed by diverting more of the differentiation process into this stream.

Another interesting finding was that germ cells arise from stem cells originating in the amnion, the thin translucent membrane containing the fluid surrounding the embryo, as well as the gastrula-forming cells that belong to the baby proper.

Finally, they found that the gene activation patterns leading to germ cell formation are nearly the same, whether it is an embryonic stem cell or an iPSC. This proves they are using the right technique to form the germ cells.

Clark says, “Now we’re poised to take the next step of combining these cells with ovary or testis cells.” These germ cells are not yet decided on whether to develop into sperm or egg cells, and this depends on the molecular signals they receive, whether from the ovary or the testis.

The researchers say, “Through this work, we uncovered the human germline trajectory and discovered the identity of potential peri-implantation progenitors for hPGCs.”

The researchers hope they will eventually be able to coax the iPSCs formed from the patient’s own skin cells to differentiate into germ cells and into ovarian or testicular tissue. This could be used to let each person have his or her germ cells created in the laboratory. The process, however, is a long-drawn-out one and will require intensive research and work.

A step too far?

These techniques have been restricted to laboratory use, and are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in humans, nor have they undergone human testing.

It is obvious that such experiments involve the abundant use of human pre-implantation embryos. Though ethical approval norms are fulfilled, such testing nonetheless raises numerous other ethical issues. Again, the true motivation of the research remains in doubt since the lack of value for potential human life shown by such experiments makes it difficult to believe that making it possible for infertile couples to have babies is the real incentive.

Finally, the potential for misapplication of this technology is obvious, just one example being its use to allow both sperm and egg cells to be created from the same patient, nurtured by both ovarian and testicular tissue derived from that patient, and eventually giving rise to a single-parent zygote. One hopes that scientists will not allow their curiosity to run rampant but rein it in within appropriate bounds rather than ruin human life with unnecessary technology -simply because they can.

Source:

Journal reference:

Human Primordial Germ Cells Are Specified from Lineage-Primed Progenitors Chen, Di et al. Cell Reports, Volume 29, Issue 13, 4568 - 4582.e5, https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)31574-8