A new Europe-wide study reveals that acute flaccid myelitis, a polio-like illness striking children, is slipping through the cracks in national surveillance, just as viral outbreaks may be driving case surges.

Study: Acute flaccid myelitis in Europe between 2016 and 2023: indicating the need for better registration. Image Credit: rob9000 / Shutterstock

Study: Acute flaccid myelitis in Europe between 2016 and 2023: indicating the need for better registration. Image Credit: rob9000 / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal Eurosurveillance, a large team of researchers from various institutions across Europe examined the incidence, causes, and national surveillance strategies for acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) across European countries from 2016 to 2023.

Background

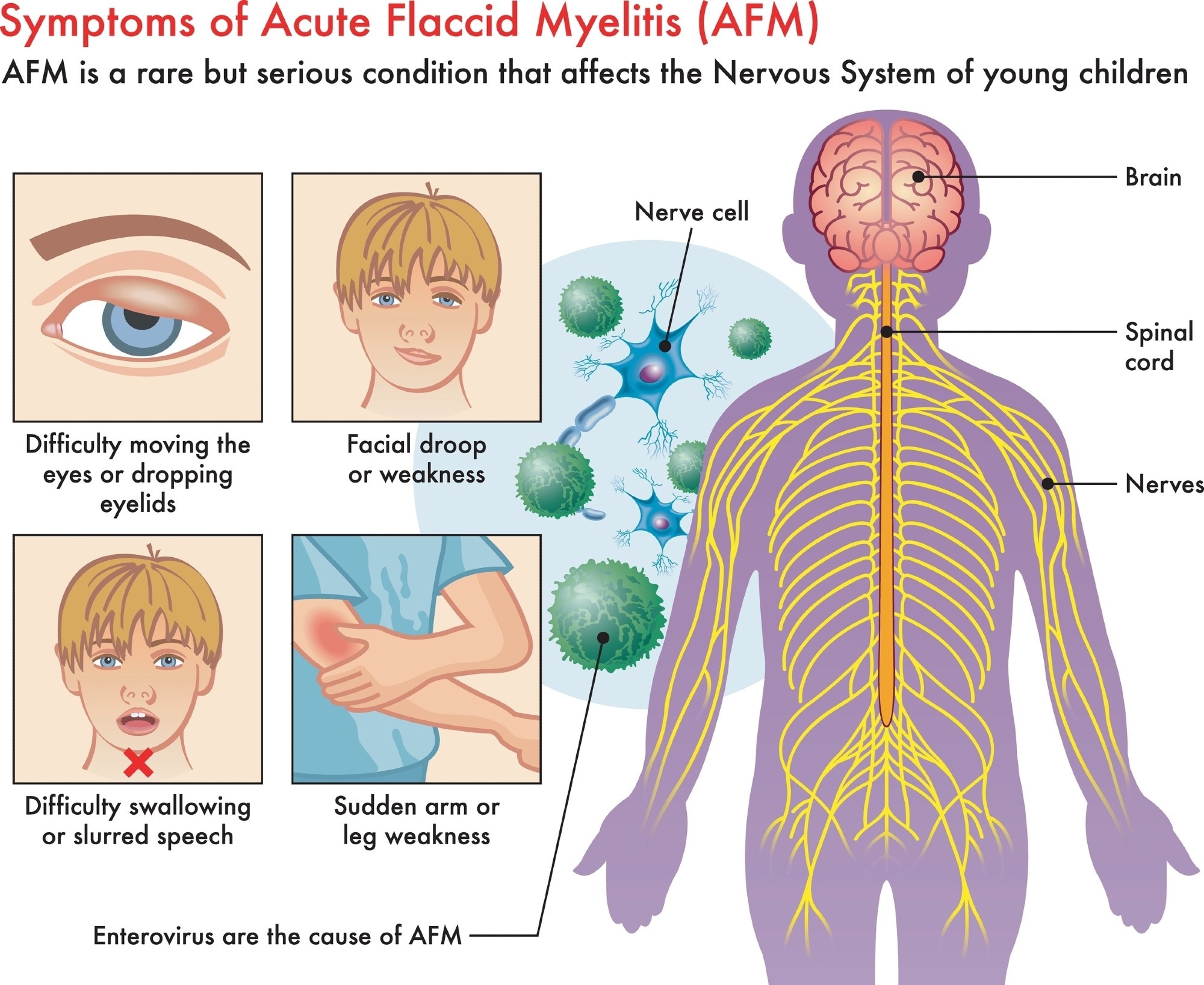

Imagine your child suddenly losing the ability to move their arms or legs. This frightening reality is the hallmark of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a rare but serious neurological condition that primarily affects the spinal cord in children under the age of 10. Its symptoms mimic those of polio, though it is caused by other viruses. I

n recent years, spikes in AFM cases have coincided with outbreaks of enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), raising concerns about a possible association. Despite the risk of paralysis and long-term disability, AFM remains largely underreported in Europe. Better surveillance is needed to understand its impact and improve preparedness. The exact triggers, natural history, and mechanisms of AFM are still being investigated. Further research is urgently needed to accurately determine the true incidence of AFM, clarify its viral triggers, and develop effective surveillance systems that can support timely diagnosis, treatment, and outbreak response.

About the study

A cross-national survey was distributed to members of the European Non-Polio Enterovirus Network (ENPEN), which includes clinicians and laboratory experts from 28 countries. These professionals were asked to describe how AFM was monitored in their countries between 2016 and 2023. The survey included questions on surveillance strategies, any changes since the 2016 case surge, institutions responsible for virological testing, and annual case counts, including those confirmed as EV-D68.

Participants were also asked to specify whether the data were nationally or regionally sourced. Although the survey did not directly request figures on acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), a syndrome involving sudden limb weakness, some countries volunteered these numbers. Information on the type of virological testing was not systematically collected but was occasionally shared by respondents.

Responses were received from 22 institutions in 16 countries, and 18 institutions were able to provide AFM case data. Case counts, including those with confirmed EV-D68 infection, were compiled for each year from 2016 to 2023. The goal was to assess patterns in incidence and identify gaps in monitoring systems across Europe, as well as to explore the temporal relationship between EV-D68 circulation and AFM spikes.

Study results

The survey identified 130 confirmed cases of AFM across 15 European countries between 2016 and 2023. Most cases, 91 in total or 70%, were clustered in 2016, 2018, and 2022, which were years known for increased EV-D68 circulation. Among the 130 total cases, 48 (37%) were laboratory-confirmed as EV-D68-positive.

Only Norway maintained a structured surveillance system dedicated specifically to AFM. In contrast, eight countries (Austria, Belgium, Poland, Spain, Italy, Norway, Switzerland, and Türkiye) still operated legacy AFP surveillance programs that were initially created for poliomyelitis tracking. However, these systems mainly focus on excluding poliovirus and typically did not include follow-up investigations for causes like EV-D68. In Norway, respiratory samples were routinely collected from AFP cases since 2014, allowing for more precise viral identification.

Overall, surveillance approaches were inconsistent. In 12 of the 16 countries, testing for suspected AFM was done locally, while four countries relied on national reference centers. Some participants based their responses on personal experience or regional data rather than national registries, further limiting reliability.

Data from four countries, namely Spain, Poland, Norway, and Switzerland, also included AFP counts, totaling 751 cases. However, these numbers did not always correlate with reported AFM figures, suggesting that AFP surveillance alone is not sufficient to track AFM accurately. This may reflect that most AFP cases are due to other conditions, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, or possible underdiagnosis or misclassification of AFM, especially in the absence of routine viral testing.

The three peak years for AFM cases (2016, 2018, and 2022) matched global patterns, particularly in the United States (US), where the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) operates a dedicated AFM monitoring system. The consistency of European and US peaks supports the temporal association between EV-D68 and AFM surges. Still, the absence of a similar structured clinical surveillance system across most of Europe means many cases likely go undetected or unreported.

It remains unclear whether increases in reported AFM cases during periods of high EV-D68 circulation are due to actual spikes in incidence or heightened clinical awareness and reporting.

Conclusions

To summarize, this study highlights significant gaps in how AFM is tracked across Europe. Only Norway has implemented a national surveillance system focused on this disabling neurological condition. The finding that 70% of reported cases occurred during known EV-D68 outbreak years reinforces a temporal association between the virus and disease spikes. However, the inconsistent data collection and lack of routine testing mean true case numbers are probably higher. To improve detection and preparedness, a European AFM repository is being developed. This shared network aims to standardize reporting, increase awareness, and ultimately reduce the burden of this rare but potentially devastating illness in children.