Introduction

What is selenium, and why is it important?

Selenium-rich foods

Health benefits of selenium

Recommended intake and deficiency risks

Safety and excess intake

Conclusions

References

Further reading

Selenium-rich foods, from Brazil nuts to tuna, help maintain thyroid hormone balance, antioxidant defenses, and immune function when consumed in safe amounts. Balancing intake matters: too little impairs selenoproteins and immunity, while excess raises toxicity risk, so food-first strategies beat high-dose supplements.

Image Credit: Peter Hermes Furian / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Peter Hermes Furian / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Selenium is an essential trace mineral that plays a critical role in maintaining human health through its incorporation into selenoproteins, which regulate antioxidant defenses, thyroid hormone metabolism, immune response, and reproduction. Although required only in microgram quantities, selenium has a narrow safe range; both deficiency and excess can lead to significant health issues.

Deficiency has been linked to impaired thyroid function, weakened immunity, and increased risk of viral infections and cardiovascular disorders, while excess intake may result in selenosis and metabolic disturbances.

Selenium’s biological effects are mainly exerted through enzymes such as glutathione peroxidases, thioredoxin reductases, and iodothyronine deiodinases, which together maintain redox balance and regulate energy metabolism. Because selenium concentrations in soil vary widely by geography, its availability in food differs across regions, leading to global disparities in selenium status.

Populations living in low-selenium regions of Europe, Asia, and parts of Africa are particularly vulnerable to deficiency-related disorders, including Keshan disease and Kashin–Beck disease. Conversely, areas with high soil selenium, such as certain regions in South America and the United States, may experience toxicity from excessive dietary intake. Therefore, achieving optimal selenium status through balanced consumption of selenium-rich foods like Brazil nuts, seafood, meats, eggs, and grains is essential for supporting endocrine, cardiovascular, neurological, and immune health.1,4,5

What is selenium, and why is it important?

Selenium serves as a cofactor for selenoproteins, including glutathione peroxidases (GPx), thioredoxin reductases (TrxR), and iodothyronine deiodinases D1, D2, and D3. These enzymes are crucial for regulating thyroid hormone levels, protecting against oxidative stress, modulating the immune system, and maintaining reproductive health.1

The thyroid gland is particularly rich in selenium, wherein deiodinases convert thyroxine (T4) into its active form triiodothyronine (T3), thereby regulating metabolism at both systemic and cellular levels. Selenium deficiency is often associated with thyroid dysfunction, such as hypothyroidism and autoimmune thyroiditis, while supplementation has been shown to reduce thyroid autoantibodies in autoimmune thyroiditis and may improve thyroid function in some patients. 3,2,10

As a key component of GPx, selenium neutralizes reactive oxygen species (ROS), which limits lipid peroxidation by free radicals and lowers oxidative stress-induced cellular damage and inflammation. These antioxidant effects reduce the risk of developing various chronic diseases and neurodegenerative disorders.4,5

Optimal selenium levels enhance the activity of macrophages, natural killer cells, and T-lymphocytes, thereby strengthening immune defenses. Selenium-containing agents modulate inflammatory pathways relevant to antiviral defense (including those discussed in COVID-19 literature).13

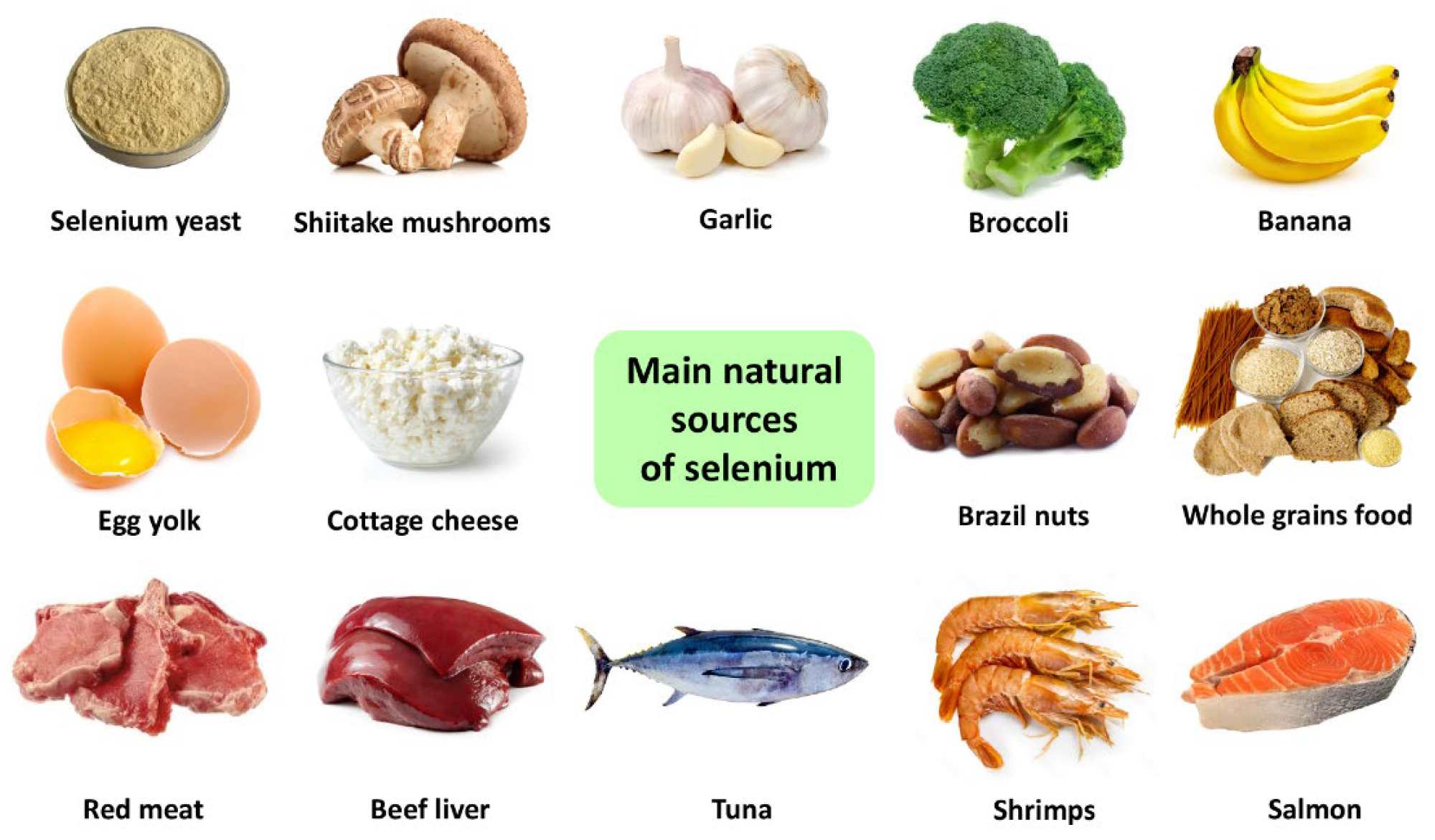

Selenium-rich foods

Dietary selenium occurs as selenocysteine (SeCys) and selenomethionine (SeMet), with content varying widely across foods and regions. Brazil nuts contain exceptionally high levels of selenium, ranging from 0.03-512 µg/g, primarily in the form of SeMet. Even a single nut can exceed daily requirements, thus making them a potent but potentially excessive source if consumed regularly.5

The key sources of Selenium from food. 4

Seafood, including tuna, sardines, salmon, oysters, and shrimp, provides up to five µg/g. Offal including beef kidney (4.5 µg/g), liver (0.93 µg/g), and heart (0.55 µg/g) is also abundant in selenium, whereas poultry, pork, eggs, and dairy products provide moderate amounts.5,6

The selenium content of whole grains, legumes, and mushrooms is primarily dependent upon soil composition. Garlic, onion, and other Allium plants, as well as Brassica vegetables like broccoli and cabbage, accumulate selenium in detoxifying forms such as Se-methyl-selenocysteine.5

Selenium levels in soil range from deficient, with less than 0.1 mg/kg in parts of Finland and Scotland, to seleniferous, as observed in dry regions of the United States, China, and South America, that will contain up to three mg/kg selenium. Factors like pH, organic matter, and redox conditions influence selenium bioavailability. Crops grown in soils with poor selenium content yield lead to selenium-deficient diets, whereas those in rich soils or fertilized with selenium accumulate higher concentrations.1,5

Selenium Content of Selected Foods

| Food |

Micrograms (mcg) per serving |

Percent DV* |

| Brazil nuts, 1 ounce (6–8 nuts) |

544 |

989 |

| Tuna, yellowfin, cooked, 3 ounces |

92 |

167 |

| Sardines, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 ounces |

45 |

82 |

| Shrimp, cooked, 3 ounces |

42 |

76 |

| Pork chop, bone-in, broiled, 3 ounces |

37 |

67 |

| Beef steak, bottom round, roasted, 3 ounces |

37 |

67 |

| Spaghetti, cooked, 1 cup |

33 |

60 |

| Beef liver, pan fried, 3 ounces |

28 |

51 |

| Turkey, boneless, roasted, 3 ounces |

26 |

47 |

| Ham, roasted, 3 ounces |

24 |

44 |

| Cod, Pacific, cooked, 3 ounces |

24 |

44 |

| Chicken, light meat, roasted, 3 ounces |

22 |

40 |

| Cottage cheese, 1% milkfat, 1 cup |

20 |

36 |

| Beef, ground, 25% fat, broiled, 3 ounces |

18 |

33 |

| Egg, hard-boiled, 1 large |

15 |

27 |

| Baked beans, canned (plain or vegetarian), 1 cup |

13 |

24 |

| Oatmeal, regular and quick, unenriched, cooked with water, 1 cup |

13 |

24 |

| Mushrooms, portabella, grilled, ½ cup |

13 |

24 |

| Rice, brown, long-grain, cooked, 1 cup |

12 |

22 |

| Bread, whole-wheat, 1 slice |

8 |

15 |

| Yogurt, plain, low-fat, 1 cup |

8 |

15 |

| Milk, 1% fat, 1 cup |

6 |

11 |

| Lentils, boiled, 1 cup |

6 |

11 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice |

6 |

11 |

| Spinach, frozen, boiled, ½ cup |

5 |

9 |

| Spaghetti sauce, marinara, 1 cup |

4 |

7 |

| Pistachio nuts, dry roasted, 1 ounce |

3 |

5 |

| Corn flakes, 1 cup |

1 |

2 |

| Green peas, frozen, boiled, ½ cup |

1 |

2 |

| Bananas, sliced, ½ cup |

1 |

2 |

| Potato, baked, flesh and skin, 1 potato |

1 |

2 |

| Peanut butter, smooth, 2 tablespoons |

1 |

2 |

| Peach, yellow, raw, 1 medium |

0 |

0 |

| Carrots, raw, ½ cup |

0 |

0 |

| Lettuce, iceberg, raw, 1 cup |

0 |

0 |

*DV = Daily Value. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed DVs to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The DV for selenium is 55 mcg for adults and children aged 4 years and older. The FDA does not require food labels to list selenium content unless selenium has been added to the food. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet. USDA’s FoodData Central lists the nutrient content of many foods and provides a comprehensive list of foods containing selenium arranged by nutrient content and by food name.

Health benefits of selenium

Selenium is essential for thyroid function, particularly the conversion of T4 into T3 by deiodinase enzymes. As a result, selenium deficiency increases the risk of hypothyroidism, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and nodular disease. Short-term selenium supplementation (e.g., 4–6 months) has restored euthyroidism in a subset of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism due to autoimmune thyroiditis, although antibody and chemokine levels may not change.7

In Graves’ disease (GD), newly diagnosed patients tend to have lower serum selenium than controls, and selenium used alongside antithyroid drugs improved FT4/FT3/TSH at 3–6 months and reduced TRAb at 6 months; effects were not maintained at 9 months.8,9

Selenium has increased vaccine-induced immunity in experimental animals, with these effects attributed to increased T-cell proliferation and natural killer (NK) cell activity. In human viral disease, a randomized trial in HIV reported that 200 μg/day selenium supplementation slowed CD4+ T-cell decline over 24 months but did not improve viral suppression or a composite clinical endpoint. Across COVID-19 studies, lower selenium/SELENOP levels are generally associated with worse outcomes, and cautious supplementation has been proposed, though high-quality RCTs are still needed.11,12,13

ROS neutralization also maintains deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and cell membranes, thereby preventing chronic inflammation and age-related cognitive decline. Selenoproteins like selenoprotein P protect neurons in the brain against oxidative damage, with pilot clinical evidence indicating that supranutritional sodium selenate can raise CSF selenium and may relate to less MMSE decline in responsive Alzheimer’s patients 14

Selenium supports fertility, as several studies have reported a relationship between selenium deficiency and both miscarriage and male infertility.6 Moreover, in cardiovascular health, observational data suggest lower CVD risk within a limited selenium status range, but randomized trials overall show no CVD benefit from selenium alone; however, a Swedish trial in older adults with low selenium intake found reduced long-term cardiovascular mortality with combined selenium (200 μg/day) and coenzyme Q10.16,15

Recommended intake and deficiency risks

Selenium requirements vary by age, sex, and physiological status. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests 26 µg/day for women and 34 µg/day for men between 19 and 65 years of age based on glutathione peroxidase activity.1

In February 2015, the German, Austrian, and Swiss nutrition societies revised selenium intake recommendations based on achieving plasma selenoprotein P (SePP) saturation. The daily reference values included 70 μg for men and 60 μg for women, with an increased demand of 75 μg/day during lactation.17

For infants, 10 μg/day and 15 μg/day are recommended for those between zero and four months of age and four to 12 months, respectively. Children should consume 15 μg/day (1-4 years), 20 μg/day (4-7 years), 30 μg/day (7-10 years), 45 μg/day (10-13 years), and 60 μg/day (13-19 years), with slightly higher requirements of 70 μg/day in teenage boys (15-19 years).17

Selenium deficiency, which is defined as intake levels below 40 µg/day, is primarily driven by low selenium in soil. Deficiency can impair thyroid hormone metabolism, increase the risk of infections, and contribute to cardiomyopathy (Keshan disease), skeletal abnormalities (Kashin-Beck disease), and chronic inflammation. Patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, including newly diagnosed GD, often present with reduced selenium levels.1,8

At-risk groups include those dependent on selenium-poor soils, strict vegans, and individuals with gastrointestinal disorders that impair absorption. Thus, maintaining adequate intake through diet is critical for thyroid function, immune defense, and long-term health.1

Safety and excess intake

Selenium exhibits a U-shaped relationship with health: insufficient status impairs selenoproteins, while excess raises toxicity risk; intakes >~400 µg/day have been associated with adverse effects. At nutritional doses, selenium acts as an antioxidant, whereas high doses of selenium can lead to pro-oxidant effects.1,4,5

Excessive selenium intake causes selenosis, a condition characterized by hair and nail brittleness, gastrointestinal upset, garlic breath odor, irritability, tremors, and, in severe cases, liver and lung damage or neurological impairment. Endocrine functions like thyroid hormone synthesis may also be disrupted, with chronic overexposure increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes.1,4

Due to variability in selenium content, particularly in Brazil nuts, which can provide extremely high doses from a single serving, moderation is essential. While supplementation may benefit populations at risk of deficiency, excessive intake must be avoided, as toxic effects can arise from both dietary sources and supplements.1

Conclusions

Achieving optimal selenium status is safest through food-based sources, including Brazil nuts, seafood, meats, eggs, and whole grains, rather than high-dose supplements. Ensuring dietary diversity by incorporating various selenium-rich foods into a balanced diet provides sufficient intake, maximizes physiological benefits, and maintains selenium within safe limits to support metabolic, endocrine, and immune health while minimizing the risk of toxicity.

References

- Gorini, F., Sabatino, L., Pingitore, A., & Vassalle, C. (2021). Selenium: An Element of Life Essential for Thyroid Function. Molecules 26(23); 7084. DOI:10.3390/molecules26237084, https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/23/7084.

- Kryczyk-Kozioł, J., Zagradzki, P., Prochownik, E., et al. (2021). Positive effects of selenium supplementation in women with newly diagnosed Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in an area with low selenium status. International Journal of Clinical Practice 75(9). DOI:10.1111/ijcp.14484, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijcp.14484.

- Hu, Y., Feng, W., Chen, H., et al. (2021). Effect of selenium on thyroid autoimmunity and regulatory T cells in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A prospective randomized-controlled trial. Clinical and Translational Science 14, 1390–1402. DOI:10.1111/cts.12993, https://ascpt.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cts.12993.

- Bjørklund, G., Shanaida, M., Lysiuk, R., et al. (2022). Selenium: An Antioxidant with a Critical Role in Anti-Aging. Molecules, 27(19), 6613. DOI:10.3390/molecules27196613, https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/19/6613.

- Sun, Y., Wang, Z., Gong, P., et al. (2023). Review of the health-promoting effect of adequate selenium status. Frontiers in Nutrition 10. DOI:10.3389/fnut.2023.1136458, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1136458.

- Mojadadi, A., Au, A., Salah, W., et al. (2021). Role for Selenium in Metabolic Homeostasis and Human Reproduction. Nutrients 13. DOI:10.3390/nu13093256, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/9/3256.

- Pirola, I., Rotondi, M., Cristiano, A., et al. (2020). Selenium supplementation in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism affected by autoimmune thyroiditis: Results of the SETI study. Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrición 67; 28–35. DOI:10.1016/j.endinu.2019.03.018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2530016419301168.

- Pedersen, I. B., Knudsen, N., Carle, A., et al. (2013). Serum selenium is low in newly diagnosed Graves’ disease: A population-based study. Clinical Endocrinology, 79, 584–590. DOI:10.1111/cen.12185, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cen.12185.

- Zheng, H., Wei, J., Wang, L., et al. (2018). Effects of Selenium Supplementation on Graves’ Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. DOI:10.1155/2018/3763565, https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2018/3763565.

- Wichman, J., Winther, K. H., Bonnema, S. J., & Hegedüs, L. (2016). Selenium Supplementation Significantly Reduces Thyroid Autoantibody Levels in Patients with Chronic Autoimmune Thyroiditis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 26; 1681–1692. DOI:10.1089/thy.2016.0256, https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2016.0256.

- Kamwesiga, J., Mutabazi, V., Kayumba, J., et al. (2015). Effect of selenium supplementation on CD4+ T-cell recovery, viral suppression and morbidity of HIV-infected patients in Rwanda: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS 29; 1045–1052. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000673, https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/fulltext/2015/06010/effect_of_selenium_supplementation_on_cd4__t_cell.9.aspx.

- Fakhrolmobasheri, M., Mazaheri-Tehrani, S., Kieliszek, M., et al. (2022). COVID-19 and Selenium Deficiency: A Systematic Review. Biological Trace Element Research 200; 3945–3956. DOI:10.1007/s12011-021-02997-4, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12011-021-02997-4.

- Mal’tseva, V. N., Goltyaev, M. V., Turovsky, E. A., & Varlamova, E. G. (2022). Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Selenium-Containing Agents: Their Role in the Regulation of Defense Mechanisms against COVID-19. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23. DOI:10.3390/ijms23042360, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/4/2360.

- Cardoso, B., Roberts, B. R., Malpas, C. B., et al. (2019). Supranutritional sodium selenate supplementation delivers selenium to the central nervous system: results from a randomized controlled pilot trial in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 16; 192–202. DOI:10.1007/s13311-018-0662-z, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13311-018-0662-z.

- Alehagen, U., Aaseth, J., Alexander, J., & Johansson, P. (2018). Still reduced cardiovascular mortality 12 years after supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 for four years: a validation of previous 10-year follow-up results of a prospective randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial in the elderly. PLoS One, 13:e0193120. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0193120, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193120.

- Zhang, X., Liu, C., Guo, J., & Song, Y. (2016). Selenium status and cardiovascular diseases: meta-analysis of prospective observational studies and randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70; 162–169. DOI:10.1038/ejcn.2015.78, https://www.nature.com/articles/ejcn201578.

- Kipp, A., Strohm, D., Brigelius-Flohe, R., et al. (2015). Revised reference values for selenium intake. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 32, 195–199. DOI:10.1016/j.jtemb.2015.07.005, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0946672X15300195.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 4, 2025