Introduction

What is postpartum hair loss?

Hair growth cycle basics

Hormonal changes and postpartum hair loss

Nutritional and metabolic factors

Stress and physical recovery

Timing and duration

When to see a healthcare provider

Practical tips for management

References

Further reading

Postpartum hair shedding is a common, typically self-limited, diffuse hair-loss pattern that typically begins a few months after delivery, as follicles shift back toward telogen. Perceived severity varies, and evaluation is important when shedding is prolonged, severe, or suggests an overlapping hair disorder.

Image Credit: BaLL LunLa / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: BaLL LunLa / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Postpartum hair loss is a common dermatologic concern after childbirth. Although often physiologic, sudden and visible shedding can be emotionally distressing and may occur alongside postpartum sleep disruption and mood symptoms. In a questionnaire-based study, a greater amount of postpartum hair loss was independently associated with postpartum anxiety (e.g., adjusted odds ratio ~4.6 for “very much” hair loss vs none on the GAD-2 anxiety subscale).1

What is postpartum hair loss?

Postpartum hair loss is often described as postpartum telogen effluvium (a diffuse, non-scarring shedding pattern) that typically begins several months after childbirth as follicles shift through the hair cycle following pregnancy-related physiologic changes.3

However, some authors have questioned whether “postpartum telogen effluvium” is a distinct, well-defined entity because objective studies have not consistently shown a statistically significant difference in shedding between pregnant and postpartum women.5

Diffuse shedding usually affects the entire scalp and is typically self-limited. Gradual improvement often occurs within the first postpartum year as normal cycling resumes, although the timing and perceived severity vary widely across individuals and studies.2

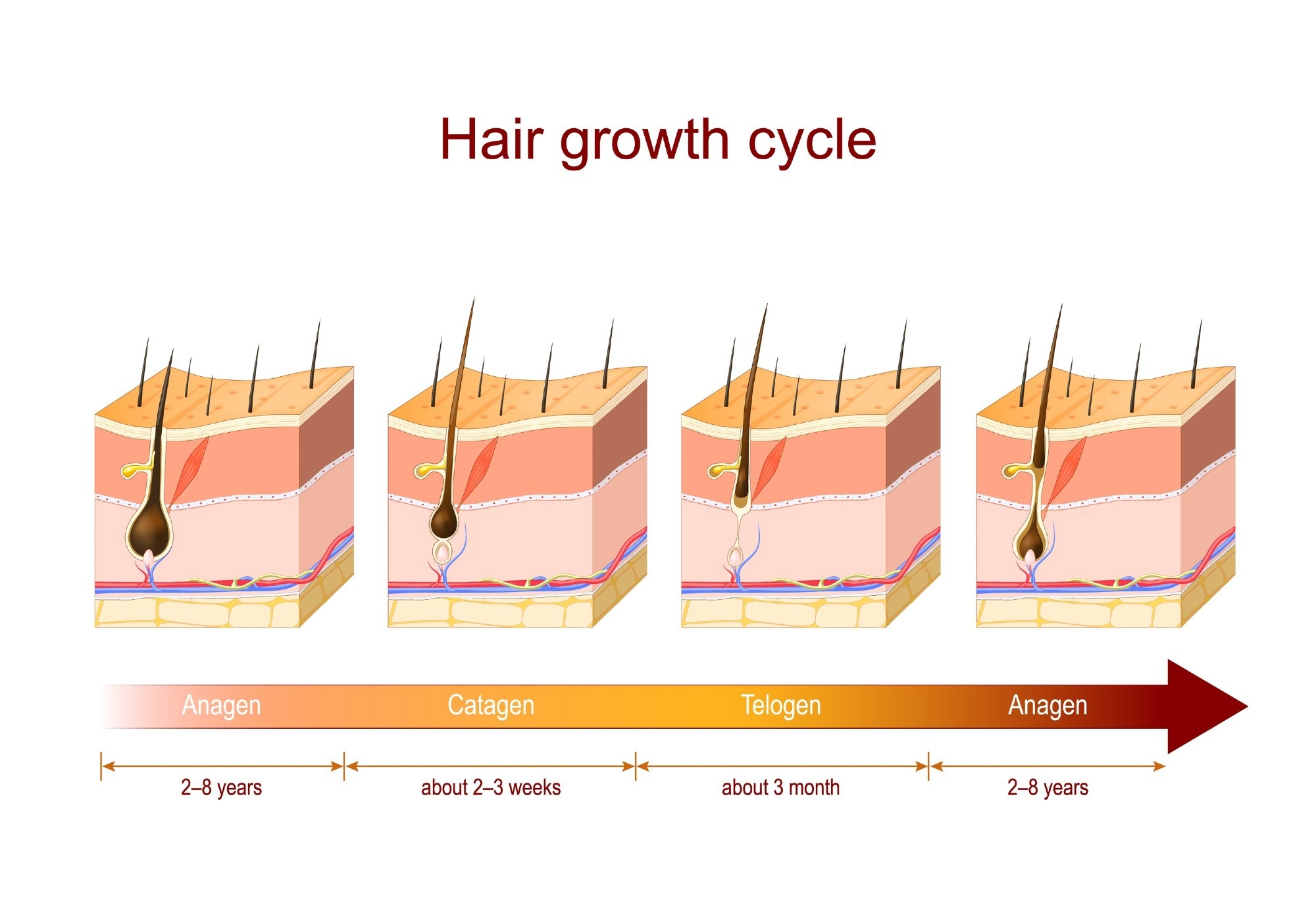

Hair growth cycle basics

The hair growth cycle comprises the anagen, catagen, and telogen phases, characterized by periods of active growth, transition, and rest, respectively. Under normal conditions, most scalp hair remains in the anagen phase, whereas a smaller proportion is in the telogen phase. Regular shedding of about 100-150 telogen (club) hairs per day is considered physiologically normal.2

During pregnancy and the postpartum period, hormonal and physiologic changes can shift this balance. After delivery, many follicles move toward catagen/telogen over subsequent months, which can increase visible shedding.11

In general populations, the scalp contains approximately 85-90% anagen and 10-15% telogen hair. In telogen effluvium, a higher proportion of follicles may be in telogen (often cited up to ~30%), contributing to diffuse shedding.4

Physiological or emotional stressors (including childbirth) can trigger telogen effluvium, and shedding often becomes apparent about 2-3 months after a trigger, with regrowth expected once cycling normalizes.3

Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock.com

Hormonal changes and postpartum hair loss

During pregnancy, many women report fuller hair and reduced shedding, consistent with a higher proportion of anagen hairs. After delivery, hormonal and physiologic changes are associated with a shift toward telogen and increased shedding in some women.11

Breastfeeding status may also be associated with measured anagen/telogen ratios in some cohorts (e.g., differences observed at about the 4th postpartum month), although findings are not uniform across time points.11

The metabolic demands of pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period can affect nutrients essential for hair follicle function. Hair follicle matrix cells divide rapidly, which may increase sensitivity to nutritional inadequacies.

Iron deficiency is a common postpartum consideration (e.g., after blood loss during delivery), but evidence linking ferritin/iron status to telogen effluvium is inconsistent across studies, and routine broad supplementation without evidence of deficiency is not supported.6,7

More broadly, micronutrients (including iron, vitamin D, and zinc) may be important when deficiency is present, but high-quality evidence for supplementation in individuals without documented deficiency is limited, and excessive intake of certain nutrients can exacerbate hair loss or cause toxicity.6,7

Stress and physical recovery

Childbirth and the transition to caring for a newborn involve significant physical and emotional change. Stress can be a trigger for telogen effluvium, and postpartum sleep disturbance is common and is longitudinally associated with postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms in some populations.10

In addition, postpartum anxiety (screened with the GAD-2) was associated with the perceived amount of postpartum hair loss in one study, and higher insomnia scores (Athens Insomnia Scale) were also independent predictors of anxiety.1

Mind-body approaches (e.g., guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, tai chi, yoga) have been studied as low-cost, generally safe interventions that may reduce stress and improve related symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period.9

Altered steroid profiles measured in hair have also been reported in postpartum depression, highlighting links between endocrine regulation and postpartum mental health, though these findings do not establish that hormone changes directly cause postpartum shedding in any given individual.8

Image Credit: KieferPix / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: KieferPix / Shutterstock.com

Timing and duration

Postpartum hair loss is commonly reported as beginning a few months after delivery. In a large questionnaire-based study, the average durations of the onset, peak, and cessation of hair loss were approximately 2.9, 5.1, and 8.1 months, respectively.3 This timing is also summarized in a related analysis describing postpartum hair loss as diffuse alopecia that begins around 3 months after delivery and lasts around 8 months.1

Reported prevalence varies markedly by study design and population: one cross-sectional clinic-based study reported postpartum hair loss in 68.4% of participants within the prior six months postpartum,2 while a questionnaire-based study reported postpartum hair loss in 91.8% of respondents (noting potential participation and recall biases).3

Some studies have reported associations between longer breastfeeding duration and postpartum hair loss; however, results differ across cohorts and time points, and causality cannot be assumed.3,11

When to see a healthcare provider

Although postpartum shedding is often self-limited, medical evaluation is appropriate if hair loss is very severe, patchy, accompanied by scalp pain/inflammation, or persists beyond about a year postpartum.

Postpartum shedding can also “unmask” other hair loss disorders (for example, androgenetic alopecia and/or traction alopecia), so persistent thinning or patterned loss warrants assessment, often including scalp examination and dermoscopy/trichoscopy.4

Cross-sectional studies have reported associations between postpartum hair loss and conditions such as anemia, hypothyroidism history, gestational diabetes, and stress measures, though these associations do not prove causation.2

Practical tips for management

Supportive strategies can reduce breakage and traction while waiting for cycling to normalize. Gentle hair care is important; avoiding tight hairstyles (tight ponytails, buns, braids, extensions) can reduce traction and scalp discomfort.

Traction-related practices can contribute to reversible early traction alopecia and, if persistent, to potentially permanent loss; therefore, loosening tension, varying styles, and using lower-tension accessories are practical preventive steps.12

For nutrition, focus on a balanced diet and correct only documented deficiencies. Reviews emphasize that supplementation without clear deficiency has limited evidence and may pose risks (including hair loss from excess vitamin A/selenium and other adverse effects).6,7

When iron deficiency is identified, monitoring and treatment goals should be clinician-guided; some expert approaches aim for ferritin targets in the ~50–70 µg/L range in selected patients, while avoiding unmonitored supplementation that can cause iron overload.7

Women are advised to consult a clinician before starting supplements, as targeted correction of documented deficiencies is essential, and excess intake of certain nutrients may be harmful or interfere with laboratory testing.6,7

References

- Hirose, A., Terauchi, M., Odai, T., et al. (2024). Postpartum hair loss is associated with anxiety. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 50(12); 2239-2245. DOI: 10.1111/jog.16130. https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jog.16130

- Ebrahimzadeh-Ardakani, M., Ansari, K., Pourgholamali, H., & Sadri, Z. (2021). Investigating the prevalence of postpartum hair loss and its associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study. Iranian Journal of Dermatology 24(4); 295-299. DOI: 10.22034/ijd.2020.248619.1217. https://www.iranjd.ir/article_143893.html

- Hirose, A., Terauchi, M., Odai, T., et al. (2023). Investigation of exacerbating factors for postpartum hair loss: A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Women's Dermatology 9(2). DOI: 10.1097/JW9.000000000000008. https://journals.lww.com/ijwd/fulltext/2023/06000/investigation_of_exacerbating_factors_for.9.aspx

- Galal, S. A., El-Sayed, S. K., & Hasan Henidy, M. M. (2024). Postpartum Telogen Effluvium Unmasking Additional Latent Hair Loss Disorders. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology 17(5); 15. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11107900/

- Mirallas, O. & Grimalt, R. (2016). The Postpartum Telogen Effluvium Fallacy. Skin Appendage Disorders 1(4); 198-201, DOI: 10.1159/000445385. https://karger.com/sad/article-abstract/1/4/198/291322/The-Postpartum-Telogen-Effluvium-Fallacy?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Almohanna, H. M., Ahmed, A. A., Tsatalis, J. P., & Tosti, A. (2018). The Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Hair Loss: A Review. Dermatology and Therapy 9(1); 51. DOI: 10.1007/s13555-018-0278-6. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13555-018-0278-6

- Guo, E. L. & Katta, R. (2017). Diet and hair loss: Effects of nutrient deficiency and supplement use. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual 7(1); 1. DOI: 10.5826/dpc.0701a01. https://dpcj.org/index.php/dpc/article/view/dermatol-pract-concept-articleid-dp0701a01

- Jahangard, L., Mikoteit, T., Bahiraei, S., et al. (2019). Prenatal and Postnatal Hair Steroid Levels Predict Postpartum Depression 12 Weeks after Delivery. Journal of Clinical Medicine 8(9); 1290. DOI: 10.3390/jcm8091290. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/8/9/1290

- Oyarzabal, E. A., Seuferling, B., Babbar, S., et al. (2021). Mind-Body Techniques in Pregnancy and Postpartum. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 64(3); 683-703. DOI: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000641, https://journals.lww.com/clinicalobgyn/abstract/2021/09000/mind_body_techniques_in_pregnancy_and_postpartum.23.aspx

- Okun, M. L. & Lac, A. (2023). Postpartum insomnia and poor sleep quality are longitudinally predictive of postpartum mood symptoms. Biopsychosocial Science and Medicine 85(8); 736-743. DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001234. https://journals.lww.com/bsam/abstract/2023/10000/postpartum_insomnia_and_poor_sleep_quality_are.9.aspx

- Gizlenti, S, & Ekmekci, T. R. (2014). The changes in the hair cycle during gestation and the postpartum period. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 28(7); 878-881. DOI: 10.1111/jdv.12188. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.12188

- Mayo, T. T. & Callender, V. D. (2021). The art of prevention: It’s too tight - Loosen up and let your hair down. International Journal of Women's Dermatology 7(2); 174. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352647521000216

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 10, 2026