The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes COVID-19, and that is spreading throughout the world is causing panic in almost all countries. With a death rate ranging from 1% to 2% in young patients but about 5%-8% in elderly and sick patients, it is capable of ravaging multiple organ systems in the human body.

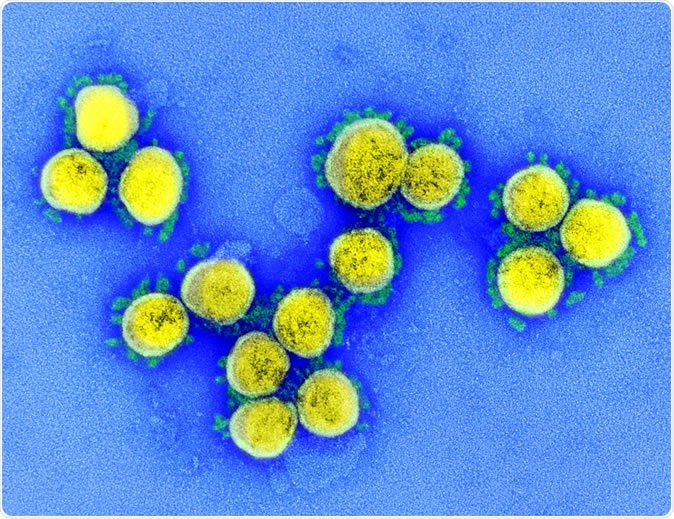

SARS-CoV-2 - Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, isolated from a patient. Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

The lungs

In most patients, COVID-19 is primarily a lung disease since the virus is a respiratory virus, just like other coronaviruses. It is typically transmitted from one person to others via respiratory droplets, often produced during coughing. The first sign is a fever and a cough. This may worsen to become pneumonia. Over 80% of infected people are thought to have a mild infection only, with the rest developing the severe or critical disease.

During early infection, the virus attacks the lung cells, both the mucus-producing and the ciliated cells. The former produces mucus to keep the lung tissue moist and protect the surface of the lung epithelium from harmful organisms. The cilia clear out foreign particles and organisms.

.jpg)

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round gold objects) emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes COVID-19. The virus shown was isolated from a patient in the U.S. Credit: NIAID-RML

Like SARS, it seems that the virus causing COVID-19 also targets ciliated cells, which are subsequently shed to fill the airways with inflammatory fluid and debris, causing bilateral pneumonia and shortness of breath.

At this stage, the immune system is activated, sensing the presence of the virus. The lung fills with immune cells that remove the damaged cells and repair the lung tissue. This is usually a carefully regulated process that keeps the damage localized to the areas that are infected. However, occasionally a hyperactive immune system causes more harm than good, and the lungs become still more congested with fluid.

The third stage begins with increasing lung damage and eventually, respiratory failure in some patients or residual lung injury in some survivors. The characteristic honeycomb appearance of the lungs in a person with severe COVID-19 infection closely resembles that produced by the SARS virus. This is thought to be due to ‘holes’ in the lung tissue caused by excessive immune activity, resulting in scars that protect the lungs from further damage but also increase lung stiffness.

The stiff lungs no longer support adequate gas exchange between the body and the atmosphere, which the accompanying inflammation causes the thin membranes to separate the blood vessels from the lung alveoli and to become leaky, pouring more fluid into the lungs and making them still less able to carry out oxygenation. As Friedman says, “In severe cases, you basically flood your lungs, and you can’t breathe. That’s how people are dying.”

The gut

Like the SARS virus, the novel coronavirus binds to receptors on the gut epithelium, to thrive within these cells, causing damage and diarrhea. Two studies have detected the virus within the stool samples of infected patients, which could perhaps indicate feco-oral transmission is occurring, and definitely could account for the gastrointestinal symptoms.

The SARS-CoV-19 virus also binds to ACE2 receptors which appear to be plentiful in the mouth, and could perhaps be responsible for aerosol transmission of the virus.

Blood

The hyperactivation of the immune system could result in a full-scale turmoil within the body, with high liver enzymes, a low blood cell and platelet count, and a decrease in the blood pressure. Some patients have even developed severe hypotension resulting in cardiac arrest and acute cessation of kidney function. The question that virologists would like to answer is whether this is due to the virus itself or due to the off-target effects of the cytokines released during the intense inflammatory process. Cytokines are chemicals released by the immune cells to attract more immune cells to the site of inflammation or injury. Their role is to destroy the infected cells and thus stop the advance of the invading virus by preventing its proliferation within these cells.

With a severe coronavirus infection, the cytokine release can get out of hand, resulting in a disordered and wild killing of cells, infected or not. This can cause severe inflammation due to the release of intracellular components from the killed or dying cells. This results in the weakening of pulmonary blood vessels, which literally bleed into the lung alveoli or air sacs.

The cytokines also affect the heart and other blood vessels, causing decreased blood supply to multiple organs, which in turn results in severe damage across the board. The final outcome in the most critical cases is multi-organ failure, caused by excessive cytokine activity and weakened heart action that compromises the blood supply to the rest of the body. Thus the cytokines are as or more important than the virus itself in generating tissue damage to the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys.

The liver

The abundant blood supply to the liver ensures easy entry for the novel coronavirus. Once infected, the liver function is impaired. The liver is among the busiest and most essential of all organs apart from the brain and the heart, taking care of detoxifying thousands of substances from our food, building up various nutrients for the body’s needs, and creating bile to help fat absorption.

Liver injury is quickly compensated for by the regeneration of new liver cells, which makes the liver extremely tough and resilient to injury. With novel coronavirus infection, the liver damage that causes liver enzymes to spill over into the blood could be direct or collateral damage caused by the violent immune response. Liver failure has never been the only cause of death in patients with SARS infection, according to experts.

The kidneys

As in the previous SARS and MERS epidemics, the current novel coronavirus also causes acute kidney injury in some patients, though this is rare. However, the consequences are almost always fatal. The virus seems to attack the kidney tubules, not selectively, but by causing low blood pressure, sepsis, or metabolic disruption. Some drugs may also precipitate renal injury, while in more severe cases, the cytokine storm caused by intense inflammation is responsible. The multi-organ damage, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and antibiotics could also be potential factors triggering kidney failure.

One area which remains relatively untouched is vertical transmission, which has never been found to happen with either the novel coronavirus or the earlier viruses.

What happens when you're infected with the COVID-19 coronavirus? | DW News

Sources:

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print 10 March 2020]. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0504

- Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, et al. Histopathologic Changes and SARS–CoV-2 Immunostaining in the Lung of a Patient With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print 12 March 2020]. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0533

- McKeever, A., (2020). Here’s what coronavirus does to the body. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/02/here-is-what-coronavirus-does-to-the-body/

- Mole, B., (2020). Don’t Panic: The comprehensive Ars Technica guide to the coronavirus. https://arstechnica.com/science/2020/03/dont-panic-the-comprehensive-ars-technica-guide-to-the-coronavirus/

- Beusekom, M., (2020). Study highlights ease of spread of COVID-19 viruses. http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/03/study-highlights-ease-spread-covid-19-viruses