Researchers tested the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children up to 21 years old and found the microbiome changes with age. Specific bacteria, whose abundance also changes with age, are associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection susceptibility and severity.

SARS-CoV-2 has infected hundreds of millions across the globe, but children seem to be less susceptible to this infection, contrary to other respiratory infections. The infected children also seem to have milder disease compared to adults. In addition, the infection severity even among children appears to increase with age.

The microbes in the upper respiratory system have increasingly been shown to influence virus infection susceptibility and the symptoms experienced. The microbes present in the nose and throat seem to alter the severity of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in young children. Intranasal administration of live bacteria altered immune response to influenza virus and RSV in animal models. Another study suggested that the bacteria in the nose and throat may also affect symptoms of respiratory virus infection, presumably by modulating the host immune response.

Previous studies have shown that at least a third of infected children and adolescents are asymptomatic, and if symptoms do develop, they are usually mild respiratory symptoms. Another report found only 576 hospitalizations and 208 deaths among children less than 18 years during the first six months of the pandemic in the United States.

This suggests there may be biological or immunological factors that vary with age, which alter susceptibility and severity to SARS-CoV-2. The microbiome in the upper respiratory tract undergoes significant changes in early childhood and is thought to play a role in how respiratory infections affect the host.

Difference in some bacteria between uninfected and infected children

So, researchers from Duke University and Duke University School of Medicine investigated the throat and nose microbiomes of 274 children and adolescents less than 21 years old who were in close contact with a SARS-CoV-2 infected individual to see if there is an association between the microbiome and infection susceptibility. They published their results on the medRxiv* preprint server.

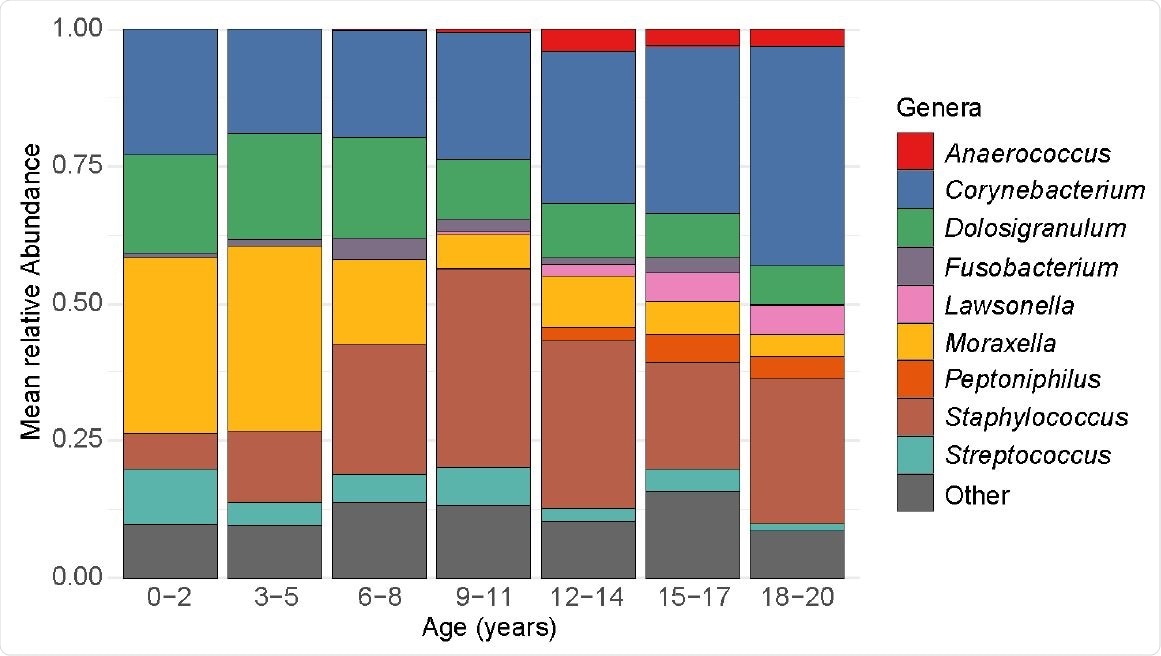

Relative abundances of highly abundant genera by age. Each bar depicts the mean relative abundances of highly abundant genera in nasopharyngeal samples from participants in a specific age category. Only the nine most highly abundant genera within nasopharyngeal samples from the entire study population are shown.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

In addition to collecting swab samples, the team also collected exposure and socioeconomic information via questionnaires. Based on the data collected, the study participants were categorized into uninfected, infected without respiratory symptoms, and infected with respiratory symptoms. Bacterial community composition in the swab samples was determined using 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing.

Of the 274 participants included in the analysis, 27% were uninfected, 32% were infected but had no respiratory symptoms, and 41% were infected and had respiratory symptoms, and they were older than the children in the other categories. A higher proportion of the infected individuals identified as Latino or Hispanic-American compared to uninfected children.

The authors found that the microbiome diversity in the throat and nose measured using the Shannon diversity index increased with age, while the microbiome richness using another index, the Chao1 index, decreased with age. The microbiome composition also changed with age.

There was no difference in the microbiome diversity between infected and uninfected individuals. However, the microbiome richness was higher in the individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. In addition, two amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) of the genus Corynebacterium were more abundant in the infected children than in uninfected children. These two ASVs also increased with age irrespective of whether the children were infected or not.

Comparing the microbiomes of infected children with and without respiratory symptoms, the team found that the microbiome was different between them. The two Corynebacterium associated with infected individuals were also higher in those with symptoms and there was a decrease in the abundance of D. pigrum in those with symptoms.

Changing microbiome alters infection susceptibility

Previous studies have shown the interaction of Corynebacterium and D. pigrim with the human nasopharynx is important. Greater Corynebacterium amounts have been negatively associated with Streptococcus pneumonia in infants and children.

The researchers also found two other bacteria of this genus that were higher in those with symptoms along with bacteria from other genera. These were positively associated with increasing age and a few were found only in children older than 12 years.

Thus, the results show that the nasopharyngeal microbiome changes continue to develop through childhood, and these changes are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and its symptoms. The changing microbiome in children likely plays a role in the susceptibility and severity of SARS-CoV-2. Thus, manipulating the upper respiratory microbiome could be a potential method of treatment of respiratory viruses.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Hurst, J. H. et al. (2021) Age-related changes in the upper respiratory microbiome are associated with SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and illness severity. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.20.21252680, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.20.21252680v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Hurst, Jillian H, Alexander W McCumber, Jhoanna N Aquino, Javier Rodriguez, Sarah M Heston, Debra J Lugo, Alexandre T Rotta, et al. 2022. “Age-Related Changes in the Nasopharyngeal Microbiome Are Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection and Symptoms among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 75 (1): e928–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac184. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/75/1/e928/6542968.