New research reveals how the vaginal microbiome can sabotage antibiotic treatment, explaining why bacterial vaginosis keeps coming back, and what it will take to finally stop it.

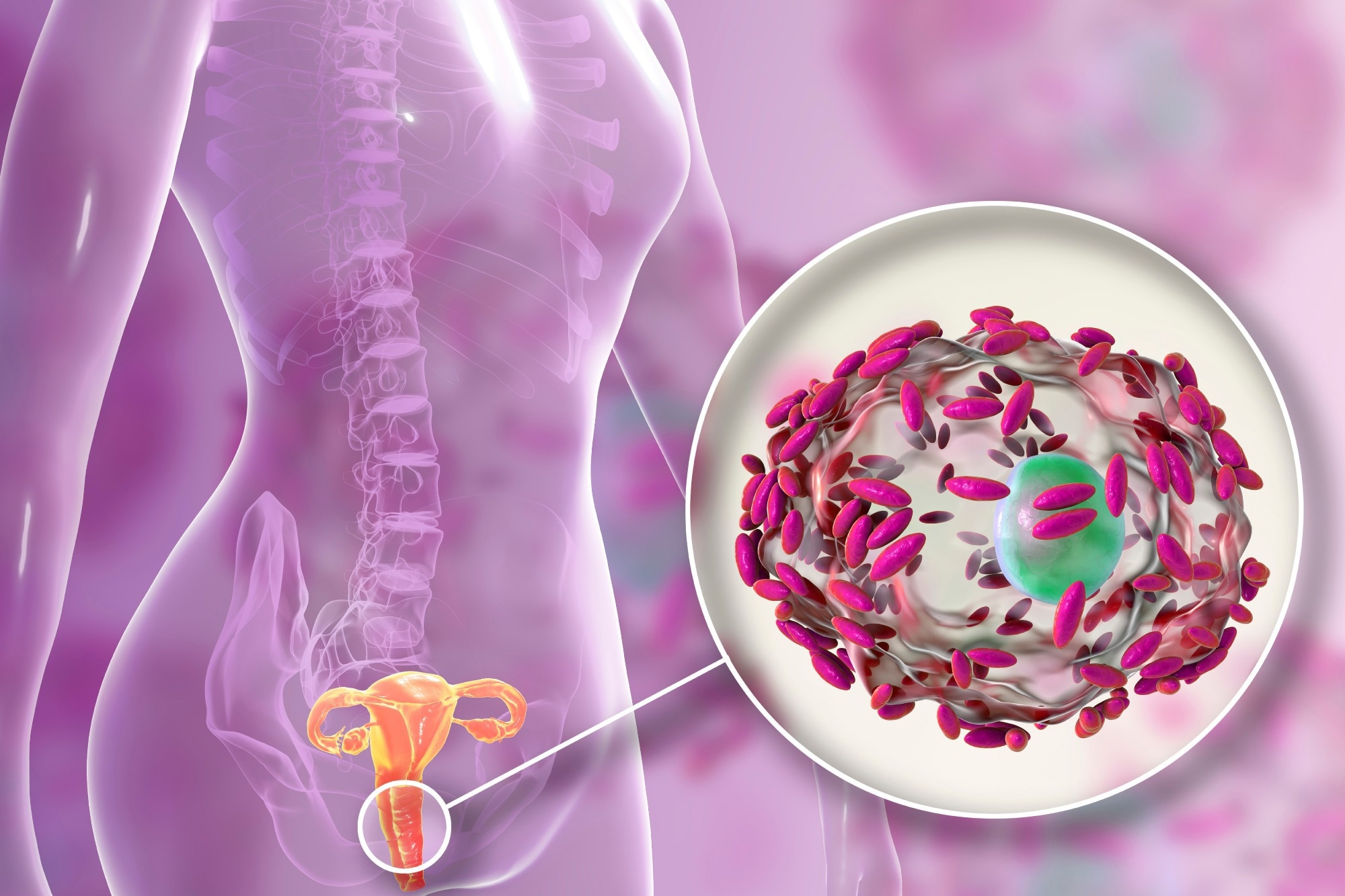

Study: Vaginal pharmacomicrobiomics modulates risk of persistent and recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Image credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Study: Vaginal pharmacomicrobiomics modulates risk of persistent and recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Image credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Scientists have reviewed the available literature to document the effect of vaginal microbiome-drug interactions on the efficacy of antibiotics against recurrent bacterial vaginosis (BV). This review has been published in Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes.

Bacterial vaginosis: Prevalence, symptoms, and diagnosis

BV is a common infection occurring in women of reproductive age causing discomfort and pain in the vagina. Although the majority of BV patients experience no symptoms, some women may have a prominent vaginal discharge with a fishy odor, along with burning and itching sensation.

BV is characterized by vaginal bacterial dysbiosis, particularly a loss of Lactobacillus, which may pose severe health threats. For instance, it increases the risk of sexually transmitted infection (STI), pelvic inflammatory disease, preterm birth, and preeclampsia in pregnant women.

Global prevalence of BV varies significantly. A recent survey estimated that approximately 30% of US women of reproductive age have BV, and this number increases to more than 50% in sub-Saharan African women.

Since no single causative agent of BV is known, it is diagnosed using the Nugent Score. It is also diagnosed clinically through nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) or by identifying the presence of at least three Amsel criteria, including a pH greater than 4.5, characteristic homogeneous milk-like vaginal discharge, a fishy odor, and 20% clue cells.

However, the authors emphasize that routine screening for asymptomatic BV is not generally recommended, as treatment may not significantly reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes.

High recurrence rate of bacterial vaginosis

Although antibiotic therapy, such as metronidazole, tinidazole, or clindamycin, is recommended to treat BV, a high recurrence rate within one to six months of treatment has been recorded in approximately 20% to 70% of women.

Key contributing factors, rather than a single cause, to high BV recurrence rates are the persistence of protective bacterial biofilm, and antibiotic resistance within the bacterial biofilm and vaginal canal. Other factors that contribute to this recurrence include non-adherence to multidose therapy, continual exchange of pathogenic bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria (BVAB) between sexual partners pre or post treatment, and inability to restore optimal levels of Lactobacillus in the vaginal microbiome.

How vaginal pharmacomicrobiomics affect the efficacy of antibiotic therapy?

Pharmacomicrobiomics involves the interaction between drugs and microbes, which is crucial for enhancing the scope of precision medicine. It focuses on understanding how microbiome variations affect drug disposition, toxicity, and efficacy. The microbiome present in various anatomic sites, such as the mouth, gut, skin, lungs, and vagina, may either improve or hinder the efficacy of drugs.

Overexpression of a DNA repair protein (RecA) in Bacteroides fragilis, a common gut and vaginal commensal bacterium, elevates resistance to metronidazole. Previous studies have indicated that oral metronidazole only temporarily reinstates healthy vaginal microbiota in patients with recurrent BV. A higher prevalence of Prevotella before treatment and Gardnerella post-treatment has been associated with enhanced risk of BV recurrence.

Many scientists have hypothesized that vaginal microbial dysbiosis is associated with modifications in drug disposition, activity, and toxicity, which contributes to antibiotic resistance and adverse reproductive outcome due to genital infection. For instance, the metabolism of the anti-HIV drug, tenofovir (TFV), by Gardnerella vaginalis has been linked to reduced HIV prevention efficacy. TFV reduced HIV incidence by only 18% in African women with G. vaginalis-dominated (BV-like) microbiota and 61% in women with Lactobacillus-dominant microbiota.

Host-specific and drug-specific factors determine the systematic distribution of drugs in different body parts. Multiple studies have shown that a dysbiotic female genital tract causes BV to increase the local pH by trapping ions that reduce the effectiveness of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). It also promotes alterations in other factors essential for the drug compound to migrate across the female genital tract compartment to treat BV.

Previous studies have also shown that T-cell uptake of TFV is influenced by alterations in vaginal microbiota and pH, contributing to the drug's inconsistent efficacy in BV-positive individuals. An abundance of specific microbes, such as Lactobacillus, may alter the movement of drugs across the genital tract by modifying local drug transporters in a pH-dependent or independent manner. Bacteroides and Prevotella are two common BVAB highly resistant to metronidazole by altering pyruvate fermentation.

The importance of vaginal pH on drug efficacy has also been shown in labor induction for term or preterm birth. It has been speculated that vaginal microbiota could indirectly influence the effectiveness of drugs by altering host drug metabolism and producing bacterial metabolites that compete with the drug receptor.

Reproductive hormones directly regulate the composition and abundance of the vaginal microbiome during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, which may influence how drugs are absorbed and metabolized, particularly when using vaginal inserts or pessaries.

Transporters recognize and export various antibiotics, including β-lactams, macrolides, and aminoglycosides, to their target sites. Multiple studies have shown that G. vaginalis, a renowned BVAB, upregulates efflux pumps and ABC transporters, which significantly contribute to bacterial colonization and infection of host tissues and multidrug resistance by actively eliminating various antibiotics and metabolites from bacterial cells.

The authors hypothesize that transport proteins expressed on vaginal epithelial cells and bacteria may be exchanged via extracellular vesicles. This speculative but plausible mechanism could further contribute to resistance and drug clearance. In addition to resistance, transporter proteins may influence how efficiently antibiotics reach and accumulate in vaginal tissues, potentially explaining some cases of treatment failure due to insufficient local drug exposure.

Conclusions

The current study hypothesized that the efficacy of recommended antibiotics for treating BV is reduced by vaginal microbiota-associated factors including pH and metabolism, leading to antibiotic resistance. Therefore, to improve therapeutic outcomes and decrease the incidence of persistent and recurrent BV, it is essential to consider the vaginal microbiome-drug interactions and efficacy of antibiotics against recurrent BV.

The authors emphasize exploring novel strategies to enhance treatment, including probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, and bacteriophage therapies. They also suggest investigating the potential of transporter/enzyme inhibitors and new drug delivery systems to improve local drug exposure in the vaginal tract.

They conclude that future research should leverage experimental models such as vaginal organ-on-chip systems and personalized metagenomic profiling to better understand these interactions and guide individualized treatment approaches.

Download your PDF copy now!

Journal reference:

- Amabebe, E. et al. (2025) Vaginal pharmacomicrobiomics modulates risk of persistent and recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. 11(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00748-0. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41522-025-00748-0