The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in many frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) being infected with the causative agent of this disease, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In a study available on the preprint server medRxiv*, a team of researchers in Victoria, Australia, performed state-wide SARS-CoV-2 genomic epidemiological investigations to recognize health care worker transmission dynamics and support optimizing healthcare system readiness for similar future outbreaks.

Study: State-wide Genomic Epidemiology Investigations of COVID-19 Infections in Healthcare Workers – Insights for Future Pandemic Preparedness. Image Credit: Halfpoint/ Shutterstock

Study: State-wide Genomic Epidemiology Investigations of COVID-19 Infections in Healthcare Workers – Insights for Future Pandemic Preparedness. Image Credit: Halfpoint/ Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Genomic sequencing was performed on all COVID-19 cases in Victoria, Australia. The team combined genomic and epidemiologic data to investigate the source of HCW infections across multiple healthcare facilities (HCFs) in the state. Phylogenetic analysis and fine-scale hierarchical clustering were performed for the entire Victorian dataset, including community and healthcare cases. Facilities provided standardized epidemiological data and putative transmission links.

A preprint version of the study is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

The study

The study was conducted between March and October 2020. It was identified that approximately thousand two hundred and forty healthcare workers were infected with SARS-CoV-2. However, only seven hundred and sixty-five were included in this study. The genomic sequencing was successful for six hundred and twelve cases from this genetic pool, around 80% of the cases. Thirty-six investigations were initiated across twelve healthcare facilities.

Moreover, the genomic analysis showed that the multiple source introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into facilities was more common than the single-source introduction. Nonetheless, the major contributors to healthcare worker's acquisitions included the movement of staff and patients between wards and facilities. Also, the characteristics and behaviors of individual patients included the super-spreading events.

There were key limitations at the healthcare facility level that were identified. Firstly, a common finding from the healthcare facilities was that many infections emerged from the movement of staff or patients. These included individuals while pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic. At one particular facility, a single patient was discovered to have spread infections in two wards due to movement while asymptomatic. The identification of such cases allows the facility to make better screen tests available and limit individuals' movement from one ward to another.

Secondly, during this study, it was found that the elderly patients with degraded mental states were exhibiting behaviors that increased the spread of COVID-19 infections. The patients who had delirium or dementia were often found wandering with the infections and coughing, sneezing, shouting, or singing around the facilities. Because of these behaviors and the additional need for medical care, they were found to be spreading the infection rampantly.

Thirdly, only the inputs from various settings will lead to a proper conclusion of transmission of the infection. When the investigations were limited to a single ward, it was found to have a limited utility compared to when performed at large facilities with high numbers of positive cases. It is thus important to conduct further such studies in various settings to conclude transmission.

Finally, the study showed that multiple collaborative meetings with healthcare facilities provided a chance to educate clinicians about the efficacy and barriers of genomic analyses. This was enabled by sharing initial findings from the genomic analysis and adding additional important epidemiological data to aid with interpretation. Another data set missing in this study was the spread of infection amongst the healthcare workers when they are in a gathering or when they share housing. This brings scope for further studies in this area.

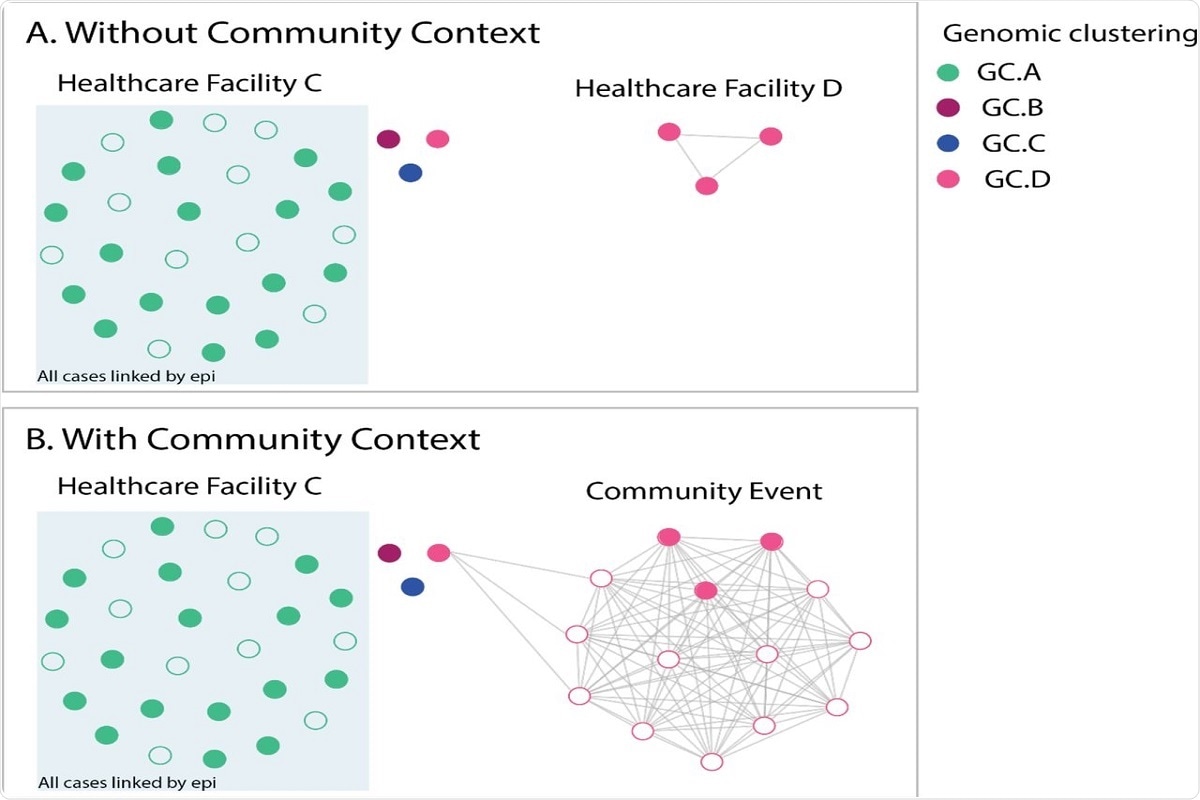

Fig 3. Comparison of genomic epidemiological analyses analysed with and without genomic data for community cases. Filled circles indicate HCWs, unfilled circles indicate non HCWs, colour indicates genomic cluster. Panel A shows analysis of cases from facility C (mostly linked by epidemiology and genomics with dominant genomic cluster GC A (green), and three additional HCW cases from different genomic clusters (genomic clusters GC B, GC C and GC D), plus three cases at facility D (related to each other) from genomic cluster GC D. In isolation, this suggests possible cryptic transmission between the two healthcare facilities. Addition of community sequences into the analysis (Panel B) demonstrated that the HCWs at both facility C and facility D likely acquired infection from a social event in the community that was attended by these cases.

Fig 3. Comparison of genomic epidemiological analyses analysed with and without genomic data for community cases. Filled circles indicate HCWs, unfilled circles indicate non HCWs, colour indicates genomic cluster. Panel A shows analysis of cases from facility C (mostly linked by epidemiology and genomics with dominant genomic cluster GC A (green), and three additional HCW cases from different genomic clusters (genomic clusters GC B, GC C and GC D), plus three cases at facility D (related to each other) from genomic cluster GC D. In isolation, this suggests possible cryptic transmission between the two healthcare facilities. Addition of community sequences into the analysis (Panel B) demonstrated that the HCWs at both facility C and facility D likely acquired infection from a social event in the community that was attended by these cases.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the scientists concluded that this study improved the understanding of HCW infections, revealing unsuspected clusters and transmission networks. In addition, they recommended the combined analysis of all HCWs and patients in an HCF and for that to be supported by high rates of sequencing coverage for all cases in the population. They further suggested that having multiple established systems for integrated genomic epidemiological studies in healthcare environments will improve healthcare worker's safety in any future pandemic.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Watt, A. et al. (2021) "State-wide Genomic Epidemiology Investigations of COVID-19 Infections in Healthcare Workers – Insights for Future Pandemic Preparedness". medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2021.09.08.21263057.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Watt, Anne E., Norelle L. Sherry, Patiyan Andersson, Courtney R. Lane, Sandra Johnson, Mathilda Wilmot, Kristy Horan, et al. 2022. “State-Wide Genomic Epidemiology Investigations of COVID-19 in Healthcare Workers in 2020 Victoria, Australia: Qualitative Thematic Analysis to Provide Insights for Future Pandemic Preparedness.” The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific 25 (August). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100487. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanwpc/article/PIIS2666-6065(22)00102-X/fulltext.