A new global review uncovers why many low- and middle-income countries struggle to produce up-to-date, evidence-based antibiotic guidelines, and how adopting WHO-backed strategies could be the key to turning the tide against resistant microbes.

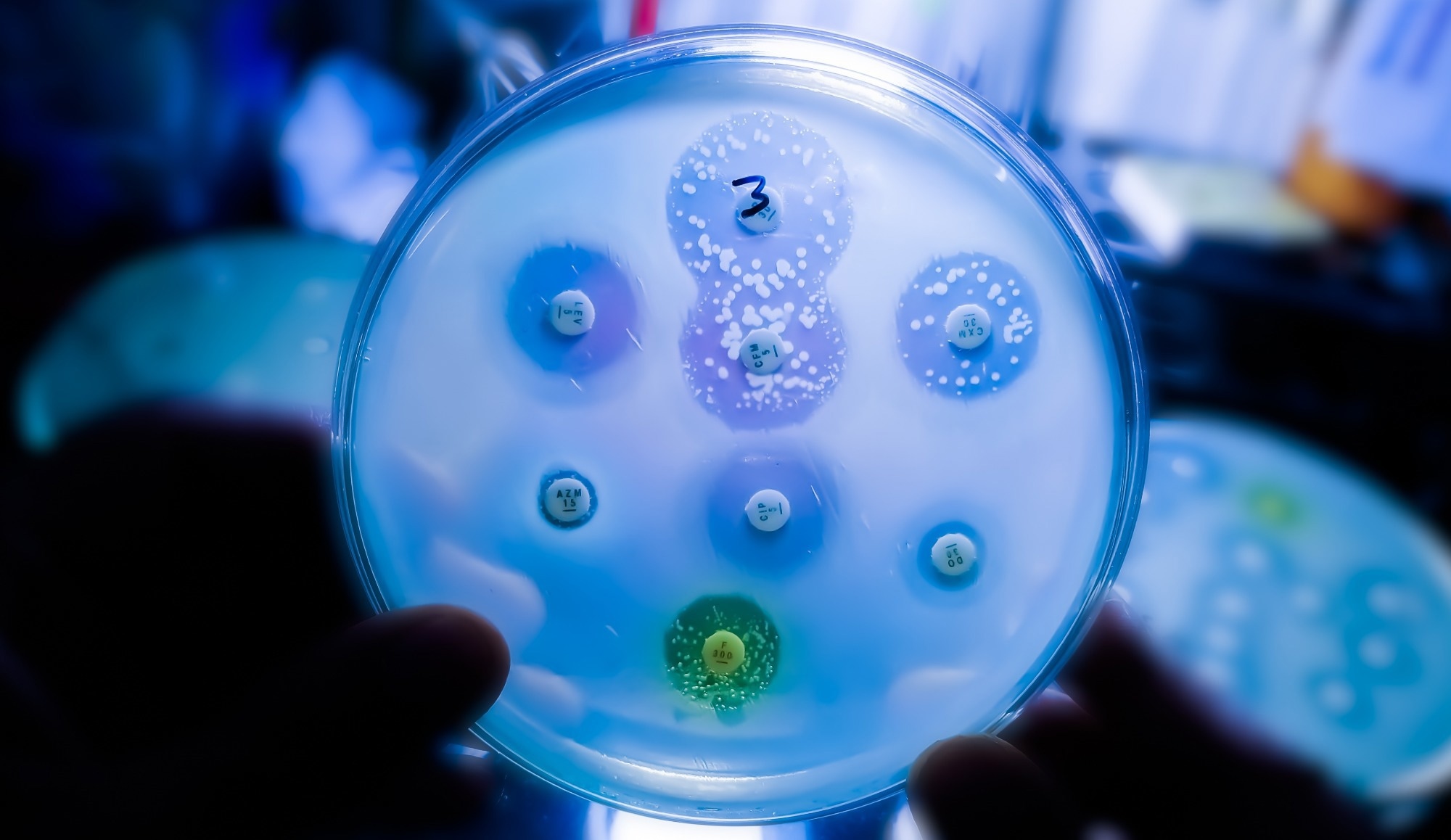

Study: Global variation in antibiotic prescribing guidelines and the implications for decreasing AMR in the future. Image credit: Saiful52/Shutterstock.com

Study: Global variation in antibiotic prescribing guidelines and the implications for decreasing AMR in the future. Image credit: Saiful52/Shutterstock.com

As antimicrobial resistance (AMR) continues to be a threat worldwide, antibiotic prescribing guidelines are essential. These must be evidence-based and updated regularly. A study published on Frontiers in Pharmacology looked at the variation in current local, national, and international prescribing guidelines, focusing on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs, including low-, lower-middle-, and upper-middle-income countries).

Introduction

The improper use of antibiotics is a significant reason for the emergence of AMR, which leads to nearly 1.17 million deaths a year. Without significant changes, this number could more than double by 2050.

The danger posed by AMR is increased in LMICs for multiple reasons. The number of infections is higher, and patients are typically uninsured or poorly insured against healthcare costs, limiting their ability to obtain appropriate antibiotics. Using unsuitable antibiotics pushes up healthcare costs and the duration and severity of illness. In addition, such infections are likely to spread more widely, and new AMR may emerge.

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed its Global Action Plan (GAP) on AMR to tackle this issue. The spin-off was the formation of National Action Plans (NAPs) for each country to promote the creation and implementation of good antibiotic stewardship policies and reduce AMR rates. Again, this is more difficult in LMICs, where training and resources are scarce.

One of the NAP's aims is to develop antibiotic prescribing guidelines in each country. These documents are tools that recommend appropriate antibiotics in various clinical situations. They are especially valuable when the evidence is limited or when there is more than one treatment option, as they make clinical care more uniform.

Publishing an antibiotic prescribing guideline is both technically challenging and expensive. For this reason, high-income countries (HICs) are more likely to have consistently relevant, evidence-based guidelines with higher healthcare demand and better resources. Top national guidelines today include the UK’s NICE, the IDSA of the USA, and the SWAB of the Netherlands.

However, this is often not the case for those from LMICs.

Physicians in LMICs are encouraged to follow published guidelines as part of their continuing education, since evidence-based recommendations can improve antibiotic prescribing quality across healthcare facilities. Such practices are often part of antimicrobial stewardship programs at all levels of healthcare and may be quality indicators. These programs are key to tracking guideline adherence and minimizing inappropriate antibiotic use.

Stewardship programs are challenging in low-resource settings like LMICs, where electronic health records (EHRs) have not yet been adopted. EHRs archive patient data and link up with other systems to guide clinical decisions. They help monitor antibiotic stewardship programs, audit institutions, and ensure guideline adherence.

LMICs also often lack effective AMR surveillance programs, hindering the development of evidence-based guidelines. Unlike wealthy countries, LMICs usually frame their policies based on expert opinion or international guidelines. These could be ill-adapted to the culture or local health needs, often predicting low adherence to published guidelines.

The current review sought to compare guidelines from various countries to see if they agree with WHO AWaRe recommendations, such as patient education and AMR stewardship. AWaRe principles prioritize Access over Watch antibiotics and avoid unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use. A United Nations General Assembly target calls for 70% of all antibiotic use to come from the AWaRe “Access” group, highlighting this global policy focus.

About the study

The scientists examined 181 guidelines, mostly from wealthy countries, with LMICs making up about 40%.

The analysis showed vast differences in how guidelines were developed, modified, and implemented across regions. It confirmed that guidelines originating from LMICs are more likely to be unstandardized, over 10 years old without updates, and leave more gaps.

Only one in five used the standard Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, almost always from high-income countries. Three other notable areas more commonly included in HIC guidelines were education, AMR surveillance, and antimicrobial stewardship strategies.

Many guidelines, especially those from LMICs, did not stress the importance of patient education. The same trend was seen in the lack of implementation strategies, including audit, feedback, or performance indicators. This gap is probably due to constraints on digital health infrastructure and spending.

Most guidelines mentioned patient communication, but modern strategies were not incorporated into LMIC guidelines, which, unlike those from HICs, generally had minimal patient-targeting material.

While HIC guidelines typically integrated AMR data, LMIC guidelines often did not, partly due to outdated surveillance systems. Robust surveillance would require nationwide data collection in a standardized format, timely data submission, and incorporation into updated guidelines. Without locally representative data, antibiotic prescribing is likely to follow broad-spectrum patterns.

Some LMICs are now working to make their AMR surveillance more effective and their national guidelines more locally relevant. Examples include empiric prescribing based on local susceptibility trends in Rwanda and formulary mapping in Kenya. These developments illustrate that progress is possible even in resource-limited settings, although challenges remain.

Conclusions

Countries at different income levels do not all have the same opportunity to publish rigorously researched antibiotic prescribing guidelines. The WHO AWaRe framework and Book could help advance antimicrobial stewardship, especially for LMICs, but this requires equitable reforms.

Thus, “advancing the development and implementation of standardized, context-specific guidelines aligned with the WHO AWaRe framework—and supported by equity-focused reforms—can significantly strengthen antimicrobial stewardship and help address the public health challenge of AMR.”

Increased investment in EHR systems, rapid diagnostic tools, and interdisciplinary research is essential to improve antibiotic stewardship. Cross-border application of guidelines from HICs is often attempted. However, the authors note that their review was limited to English-language, publicly accessible guidelines, which may overrepresent HIC contexts. The often-overburdened healthcare in LMICs, low research funding, and technical obstacles limit its assessment.

If the threat of AMR is to be successfully addressed, antimicrobial stewardship programs must be appropriately funded via global partnerships. Patients and practitioners must be educated to reduce pressure and expectations, especially during self-limiting viral infections.

Download your PDF copy now!