Single-cell sequencing enables researchers to examine molecular material at the individual cell level. Unlike standard bulk sequencing methods, which average data across cell populations, single-cell sequencing reveals individual cells' distinct genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic characteristics.

Image Credit: INTEGRA Biosciences

Single-cell sequencing is useful for a number of applications. For example, it can reveal cellular heterogeneity inside complex tissues, such as tumors.

It can also provide information about how different cell types or cellular states function, interact, and respond to environmental signals or disease processes.

This article explains what single-cell sequencing is and how it works, gives examples of applications, and advises you on when to use single-cell sequencing over bulk sequencing.

What is single-cell sequencing?

Single-cell sequencing is a fast-expanding discipline that encompasses a range of techniques for isolating and analyzing genomic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic material information from individual cells.

Tang et al. released the first single-cell sequencing study in 2009, sequencing the mRNA molecules of a manually selected single mouse cell.1 Since then, the technology has grown in popularity.

Today, more than one-third of all RNA sequencing papers use single-cell sequencing rather than bulk sequencing.2

Traditional bulk sequencing approaches can obscure differences between cells by using population averages, whereas single-cell sequencing reveals cell-to-cell diversity.

Think of it like a smoothie versus a fruit salad. A smoothie is made by blending all the components together, resulting in a single flavor. Similarly, traditional bulk sequencing examines a mixture of cells, yielding average molecular information about the original sample.

Single-cell sequencing, on the other hand, allows you to analyze each cell individually. It is similar to a fruit salad in that you can readily tell which flavor is coming from which fruit and how much of each fruit variety is in the salad.

How single-cell sequencing works

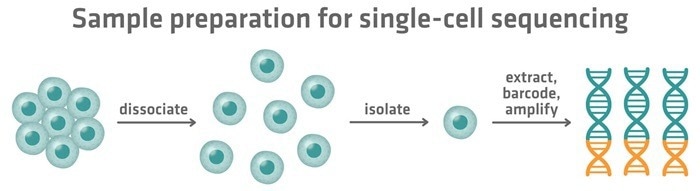

Single-cell sequencing has a similar workflow to standard bulk sequencing, which consists of sample preparation, library creation, sequencing, and data interpretation.

However, it includes additional procedures for the disassociation of biological samples to form single-cell suspensions, isolation of single cells, and handling and tracking of the molecular material extracted from the individual cells.3

Sample preparation

The process begins with conversion of biological material into a single-cell suspension. This is accomplished by dissociating cells using a combination of mechanical and enzymatic techniques.

Table 1. Common mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion protocols.

| Mechanical dissociation |

Enzymatic digestion |

| Mincing with a scalpel |

Typsin/TrypLE™ |

| Dounce homogenization |

Collagenase |

| Scraping/aspirating and dispensing with a pipette |

Elastase |

| Bead beating/milling |

Papain |

| |

Subtilisin A |

Source: INTEGRA Biosciences

The dissociated cells can then be filtered to remove clumps and prevent congestion, which could interfere with single-cell isolation later.

When a single-cell suspension is created, the sample will have a mixed population of cells. Before proceeding, cells can be sorted, enriched, or depleted to increase the quality and relevance of the sequencing data.

-

Sorting isolates the cell population of interest, allowing subsequent sequencing to target relevant cell types.

-

Enrichment involves raising the fraction of desired cells, which is particularly beneficial when the target population is scarce.

-

Depleting involves removing unneeded cells that may dilute or conceal crucial signals.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting, and density gradient centrifugation are three commonly used methods for sorting, enriching, or depleting cells.

For example, LevitasBio provides equipment that enriches samples by removing dead cells. The company suggests using INTEGRA’s ASSIST PLUS pipetting robot for automated sample preparation.

The cells in the suspension must then be isolated from each other. This isolation can be accomplished by dividing cells into individual wells of a microplate, sorting them into microwells on a chip, or encapsulating them in droplets using microfluidic technologies.

Once isolated, the molecular material from each cell is removed and amplified, as the amount from a single cell is usually insufficient for sequencing.

To minimize the cost of sequencing cells individually, each cell's DNA or RNA is assigned a unique molecular barcode. This barcode serves as an ID tag, allowing material from different cells to be combined into a single sequencing library while maintaining traceability back to the cell of origin.

Figure 1. Steps in single-cell sequencing: tissues are dissociated into individual cells, cells are isolated, and their genetic material is extracted, barcoded, and amplified for analysis. Image Credit: INTEGRA Biosciences

Library preparation

The pooled library, which includes barcoded material from various cells, must then be processed for sequencing.

Typically, a second round of barcoding is performed, with sequencing platform-specific adapters added to all nucleic acid fragments.

Sequencing

Once the pooled library is ready, it is sequenced. This stage utilizes the same sequencing platforms as bulk sequencing, with Illumina sequencing being the most widely used technology.

Data analysis

After sequencing, bioinformatics tools use the barcodes placed during sample preparation to deconvolute the data and recreate each cell's molecular profile. This allows downstream analyses to be performed, such as mutation detection, cell type identification, and comparison of gene expression patterns across tissues.

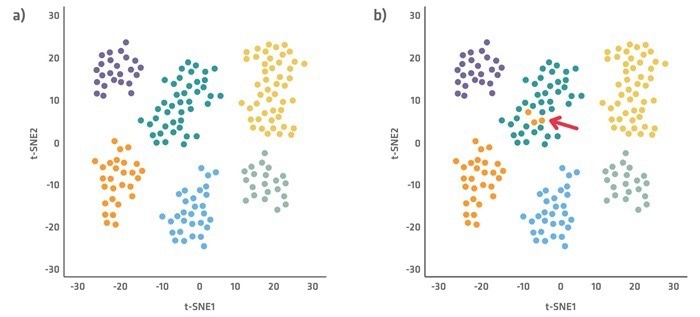

Single-cell sequencing results are frequently depicted in dimensionality reducing plots (Figure 2), with the x and y axes displaying the most important distinguishing parameters.

These charts can be created using a variety of approaches, including t-SNE (t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding) and PCA (principal component analysis), which reduce complexity and improve data visualization.

Each dot in the plot represents a cell and depicts how the key variables define it. The more similar the cells are, the closer they will appear on the plot. Examining what separates clusters and cells within a cluster can help you obtain a thorough understanding of what connects or differentiates cell types or states.

Figure 2. Example cell cluster plots using t-SNE, with each color representing a different cell type cluster. Plot a demonstrates clearly defined cell clusters, and plot b shows outlier cells. Image Credit: INTEGRA Biosciences

It is worth noting that flow cytometry and mass cytometry can both be used to quantify heterogeneity between individual cells. However, they are confined to evaluating a few dozen pre-selected markers, whereas single-cell sequencing can profile all genes present in a cell, offering a much more comprehensive picture.

Single cell sequencing applications

Single-cell sequencing has numerous applications across various fields.

Sequencing the genomes of different cells can be helpful in oncology. Tumors are genetically diverse, and even within the same tumor mass, cells can exhibit distinct mutations or copy number variations, which can influence how a tumor develops, spreads, and responds to treatment.

Single-cell sequencing can reveal the tumor's cellular heterogeneity and composition, enabling individualized and targeted therapy approaches.

Single-cell genome sequencing is also widely used in microbiome and environmental assessments. It enables researchers to determine the composition of complex microbial communities, and the genetic differences within species, by isolating and sequencing the genomes of individual cells without the need for cell growth – which is especially useful for non-culturable species.

Sequencing the epigenome, transcriptome, or proteome of individual cells is useful for understanding cellular diversity and regulation in complex systems and tissues.

For example, single-cell epigenetic, transcriptomic, or proteomic data can reveal the identification, status, and activity of numerous immune cell types, enabling researchers to gain a deeper understanding of immune responses and dysfunctions.

In oncology, these approaches can reveal epigenetic changes and gene expression patterns that differentiate various cell types present in the tumor microenvironment.

These sequencing approaches are also frequently used in developmental biology, to track the differentiation of stem cells into specialized cells, as well as in disease research to find cell-specific markers, identify therapeutic targets, or understand regulatory changes that contribute to disease.

Multi-omics applications that sequence multiple molecular layers simultaneously are also available. For example, single-cell nucleosome, methylome, and transcriptome sequencing (scNMT-seq) provides concurrent insights into nucleosome occupancy, methylome, and transcriptome at the single-cell level.

Another example of a multi-omics single-cell sequencing approach is BioSkryb Genomics' ResolveOME technology, which can amplify both the genome and the transcriptome within each cell.

Pros and cons of single-cell sequencing

Although single-cell sequencing has several advantages over bulk sequencing, it also has a few drawbacks.

Bulk sequencing is typically faster and less expensive than single-cell techniques. The protocols are simpler, allowing you to achieve better throughput at a lower cost and in a shorter time frame.

Bulk approaches can simplify the pre-processing of cell culture or tissue biopsy samples, as they eliminate the need for single-cell isolation, streamlining the workflow.

Bulk sequencing has also been used for decades, and is the most popular approach. As a result, protocols are generally well-established and precise, making them capable of producing reproducible findings.

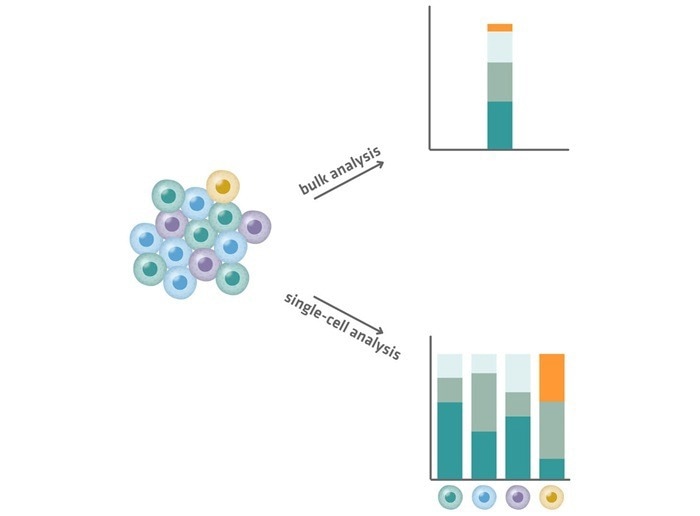

However, information from individual cells is lost during bulk sequencing, and information from rare molecular species is diluted in the average signal of the total cell population, as illustrated in Figure 3.

In a bulk RNA sequencing experiment, a small fraction of transcripts (the orange segment in Figure 3 below) may appear inconsequential due to their low quantity. In a single-cell experiment, these transcripts may be identified as important markers of a small but significant cell population (yellow cells in Figure 3 below).

The yellow cells, for example, could be cancer stem cells from a tumor sample, while the orange segments could encode a resistance factor to specific medicines, which only single-cell sequencing can detect.

Figure 3. Comparison of bulk analysis (top) and single-cell analysis (bottom). Single-cell analysis reveals cell-to-cell variability and identifies rare transcripts (yellow). Image Credit: INTEGRA Biosciences

Single-cell techniques are also better suited to spatial transcriptomic investigations, which aim to connect transcriptional patterns with their physical position within the tissue's original structure.

Spatial information is significantly lost during bulk sequencing. Researchers can slice a tissue, isolate a tiny portion of interest, and sequence it as a homogenized sample to gain gene expression data that can be linked to a specific tissue location. However, they cannot generate a fine-grained map of where specific transcripts originated.

In contrast, single-cell spatial transcriptomics approaches retain positional context. One such technique involves placing a tissue segment on a slide with barcoded capture areas. Each spot collects mRNA molecules from surrounding cells, labels them with a unique positional barcode, and reverse transcribes them. Following sequencing, these barcodes enable each read to be traced back to its exact location on the slide, resulting in a high-resolution spatial map of gene expression throughout the tissue.

Conclusion

Single-cell sequencing is a significant departure from typical bulk sequencing methods, providing new insights into cellular diversity and function.

Bulk sequencing examines pooled data from many cells and produces average signals that can obscure uncommon and distinct cell types. In contrast, single-cell sequencing examines individual cells separately to expose cell-to-cell variability and detect even the rarest cellular populations.

This basic distinction makes single-cell approaches particularly useful for obtaining precise cellular insights, tracking cell lineages, and investigating differentiation that would be unachievable with bulk methods.

Ultimately, your research aims and available resources will determine whether you utilize bulk or single-cell sequencing.

Bulk sequencing remains a viable solution for general profiling applications where population-level averages are sufficient, offering a simpler and more cost-effective workflow with established procedures.

When your research demands greater resolution at the single-cell level, sensitivity to cellular heterogeneity, or spatial transcriptomic analysis with intact positional information, single-cell sequencing becomes essential, despite its increased complexity and cost.

Table 2. Comparison of Bulk and single-cell sequencing

| Bulk sequencing |

Single-cell sequencing |

| Analyzes pooled data from many cells |

Analyzes individual cells separately |

| Provides average signal |

Reveals cell-to-cell variability |

| Masks rare and unique cell types |

Identifies rare and unique cell types |

| Used for general profiling |

Used for detailed cellular insights |

| Cannot track cell lineage |

Can track cell lineage and differentiation |

| Workflow is simpler and more affordable |

Workflow is more costly and complex |

| Limited resolution |

High resolution at single-cell level |

| Less sensitive to heterogeneity |

Highly sensitive to heterogeneity |

| Spatial information is largely lost |

Ideal for spatial analyses |

Source: INTEGRA Biosciences

References

- Tang, F., et al. (2009). mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nature Methods, 6(5), pp.377–382. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1315

- Pierre, L.T. (2023). Writing a Successful Single Cell RNA Sequencing Grant Proposal. [online] Parse Biosciences. Available at: https://www.parsebiosciences.com/blog/successful-single-cell-grant-proposals

- iBiology Techniques (2021). Single Cell Sequencing - Eric Chow (UCSF). (online) Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9VFNLLQP8c.

About INTEGRA Biosciences

INTEGRA provides innovative solutions for liquid handling and media preparation applications that serve the needs of its customers in research, diagnostics and quality control laboratories.

INTEGRA provides innovative solutions for liquid handling and media preparation applications that serve the needs of its customers in research, diagnostics and quality control laboratories.

The company’s instruments and plastic consumables are developed and manufactured in Zizers, Switzerland and Hudson, NH USA. In order to remain close to its customers, the company maintains a direct sales and support organization in North America, the UK, France and Germany, as well as a network of over 100 highly trained distribution partners worldwide.

In recent years INTEGRA has focused on developing a new and technologically advanced range of handheld electronic pipettes which are simple to use and meet the ergonomic needs of their customers. Today, the company is proud to offer the widest range of electronic pipettes in the market spanning a range from single channel pipettes up to 384 channel bench-top instruments.

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.Net, which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices, and treatments.