Introduction

An overview of the circadian rhythm

Why nighttime eating matters

Best foods to eat at night

Foods to limit or avoid in the evening

Effects on cardiometabolic health

Practical guidelines

References

Further reading

Late-night meals can quietly derail glucose control and cardiovascular health. Here’s what chrononutrition research and clinical evidence suggest you should eat, avoid, and shift earlier to protect metabolic function.

Image Credit: New Africa / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: New Africa / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Chrononutrition examines how the timing of food intake interacts with circadian biology to influence metabolic function and long-term health. Growing research in this field suggests that aligning eating behaviors with intrinsic circadian rhythms may support cardiometabolic health and reduce disease risk.2

An overview of the circadian rhythm

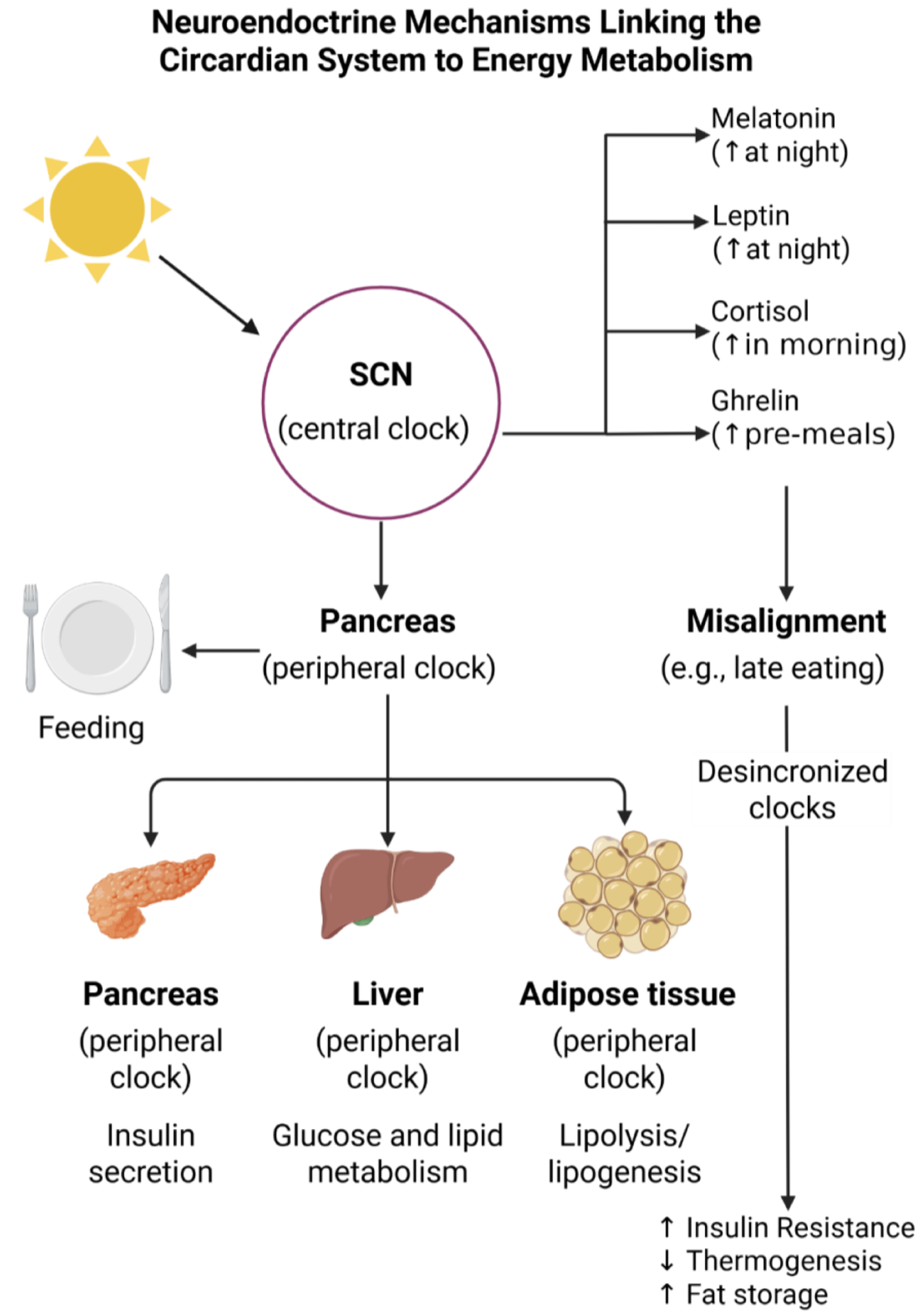

The circadian system comprises a central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and multiple peripheral clocks in metabolic tissues. Together, these clocks coordinate 24-hour rhythms in glucose regulation, lipid metabolism, blood pressure, and hormonal activity.

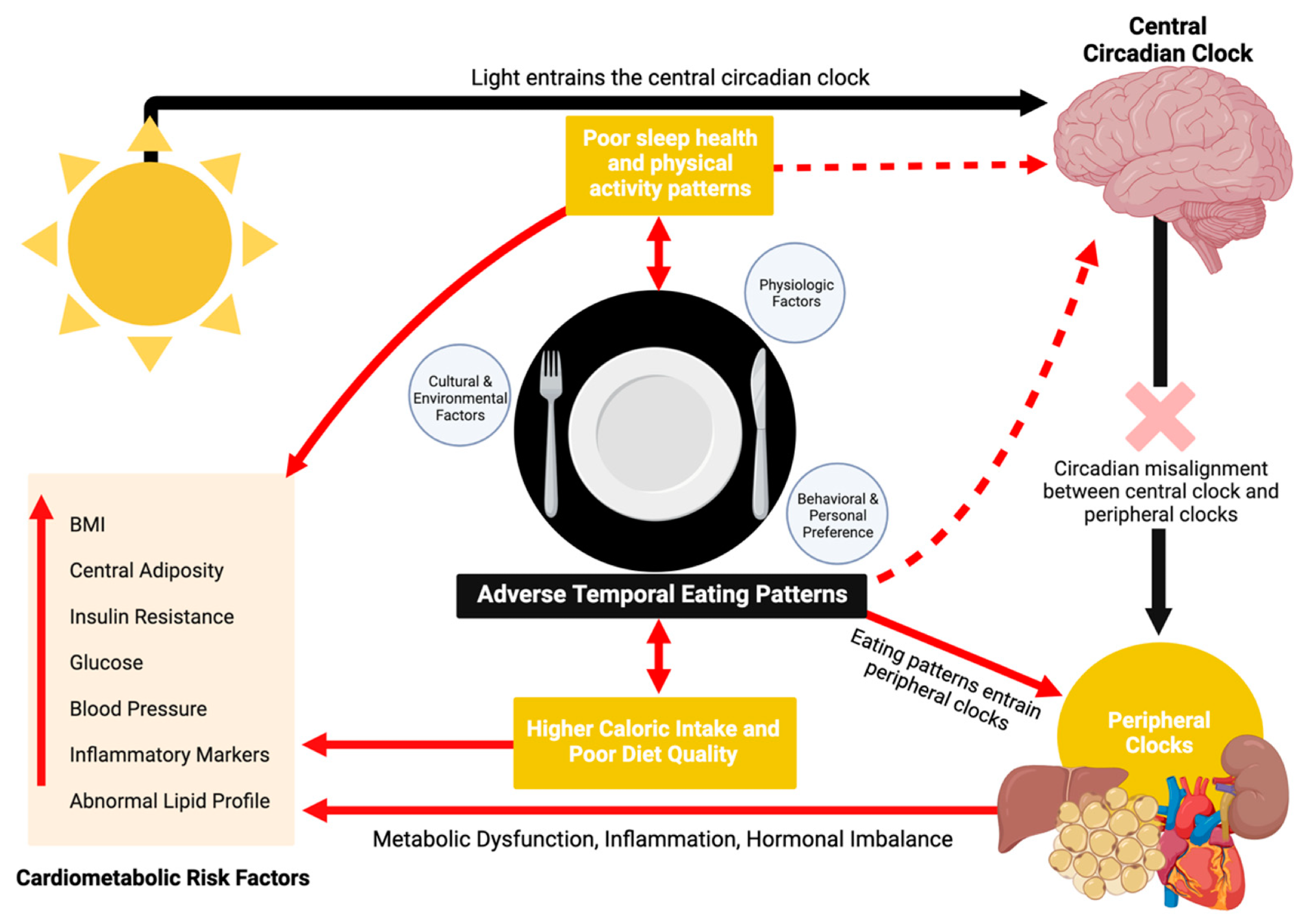

Light primarily entrains the central clock, whereas feeding patterns act as potent synchronizing signals for peripheral clocks.1 In modern environments characterized by irregular schedules, late eating, and nighttime activity, internal clocks can become desynchronized. Circadian misalignment disrupts metabolic homeostasis and is associated with impaired glucose control, reduced insulin sensitivity, and adverse cardiometabolic outcomes.12

Mechanisms linking temporal eating patterns to cardiometabolic disease. Created with BioRender.com1

Why nighttime eating matters

When meals are consumed at night, when glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity are typically reduced and circulating melatonin is higher, postprandial glucose and insulin responses can become exaggerated.2 Controlled laboratory studies show that late eating can impair glucose handling during the biological evening/night, contributing to higher nocturnal glucose excursions.3

Illustration of the bidirectional relationship between the circadian system and metabolic regulation. It emphasizes how feeding behavior and light exposure interact with the master clock in the SCN and peripheral clocks in metabolic tissues. Disruption of this network, particularly through inappropriate meal timing, contributes to metabolic dysregulation, including impaired insulin sensitivity, altered lipid metabolism, and increased risk for obesity. Abbreviations: SCN = suprachiasmatic nucleus.2

Digestive and metabolic efficiencies also weaken at night. Gastric emptying is significantly slower at night, accompanied by declining lipid oxidation levels, which delay the transition to overnight fat mobilization.

A randomized crossover trial comparing dinner at 18:00 to 22:00 found that late-night eating increased blood glucose levels, delayed triglyceride peaks, reduced free fatty acid mobilization, and reduced dietary fatty acid oxidation, without altering sleep architecture. These effects were particularly evident among individuals with earlier chronotypes, suggesting increased vulnerability.3

Cortisol is typically lower overnight, but a late dinner increased cortisol in this laboratory study, and together these circadian, metabolic, and hormonal changes may shift substrate use toward greater fat storage when late eating recurs chronically.3

Best foods to eat at night

Fiber-rich vegetables, fruits, and legumes are particularly suitable for consumption at night because they promote steady glucose absorption, minimize two-hour post-meal glycemic spiking, and enhance satiation. Legumes provide carbohydrates, protein, and soluble fiber with a low glycemic index (GI) while reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels and improving cellular insulin response. Fermented fibers in legumes also support a healthy gut microbiome, further contributing to cardiometabolic benefits.4

Low-GI proteins like fish, tofu, and fermented dairy stabilize evening glucose responses and provide tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin and melatonin, which are neurotransmitters that regulate sleep and appetite. Other tryptophan-rich foods, such as soy products, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and legumes, may support healthy sleep patterns by increasing the availability of these neural messengers.

Melatonin-rich foods like tart cherries, tomatoes, walnuts, and kiwifruit have been associated with improved sleep onset and efficiency. Magnesium-rich foods like leafy greens, legumes, seeds, and nuts also promote neuromuscular relaxation and support parasympathetic activation, which complements evening physiological wind-down.4

Caffeine-free herbal teas with chamomile, hibiscus, and peppermint may facilitate relaxation through anxiolytic, antioxidant, or digestive effects. Other botanicals including lavender, lemon balm, passionflower, and valerian have calming properties and may modestly improve sleep quality.5

Image Credit: ajie kuncoro / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: ajie kuncoro / Shutterstock.com

Foods to limit or avoid in the evening

Energy-dense evening meals high in saturated fats and added sugars can impair sleep and glucose regulation. Although isolated trials report that high-GI meals may reduce sleep-onset latency, broader epidemiological data show that high added sugar and refined grain intake are associated with poor sleep quality and an increased risk of insomnia.

Dietary habits increase the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII), with higher DII scores correlating with poor sleep quality and a greater risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Inadequate sleep increases cravings for sweets and fatty foods, which perpetuates a cycle that elevates this risk.4

Caffeine antagonizes adenosine receptors, and in controlled trials, caffeine intake reduces total sleep time and increases sleep-onset latency.6 Separately, caffeine can also reduce glucose tolerance in acute testing.7

Alcohol initially induces drowsiness but subsequently fragments sleep by delaying REM onset and reducing REM sleep duration, with a dose-response relationship observed even at lower doses.8 In real-world monitoring, moderate evening alcohol intake has also been associated with a transient increase in nocturnal resting heart rate, even when objective sleep-stage distributions show minimal change.9

Late eating can impair glycemic control and may increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Laboratory studies demonstrate that identical meals can produce higher postprandial glucose elevations later in the day, consistent with circadian regulation of glucose metabolism and reduced glucose tolerance during circadian misalignment.12

The combination of circadian misalignment and sleep restriction further reduces peripheral insulin levels and increases inflammation, with some individuals exhibiting glucose responses in the prediabetic range. Meal timing also correlates with eating behavior, as individuals who consume most of their energy after 20:00 are more likely to consume fat and alcohol, in addition to being at a greater risk of T2DM.10,11

Observational studies correlate later eating patterns with dyslipidemia, visceral adiposity, and metabolic syndrome. In a large NHANES analysis (2015–2018), longer eating duration (>12 h) and later last-meal timing were associated with a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity, and later eating midpoints were associated with a higher prevalence of elevated fasting glucose.15

Leptin-ghrelin imbalances from circadian misalignment reduce the feeling of fullness, thereby promoting hunger and contributing to weight gain, regardless of caloric intake. Studies conducted in humans and animals indicate that caloric intake during the biological rest phase shifts metabolism toward increased lipid deposition as compared with the active phase.12-14

According to the NutriNet-Santé study, each 1-hour delay in first-meal timing was associated with higher overall cardiovascular disease risk, and point estimates for later first/last meal categories suggested higher risk (with stronger patterns reported in women), although some categorical comparisons did not reach conventional statistical significance.16

Early time-restricted eating (TRE) improves insulin responsiveness, enhances fat oxidation, and increases 24-hour energy expenditure. Studies comparing early- and late-eating patterns demonstrate that consuming meals earlier in the day may improve β-cell function and lower mean glucose levels.16

Shift work forces sleep-wake and eating-fasting cycles to occur at biologically inappropriate times, thereby increasing the risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Night workers often exhibit suppressed melatonin and altered cortisol rhythms, which disrupts circadian activity and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

Eating at night further impairs metabolism, as late meals reduce resting energy expenditure, worsen glucose tolerance, and increase postprandial glycemia. At the molecular level, chronic shift schedules limit clock-gene expression to attenuate β-cell activity.2,16

How to kick those late-night food cravings

Practical guidelines

A recent meta-analysis of 30 randomized controlled trials confirms that TRE reduced body weight and fat mass, including in trials with isocaloric controls, but also observed small average reductions in fat-free mass.18 These findings are consistent with the possibility that circadian-aligned eating patterns contribute modest metabolic benefits beyond calorie reduction in some settings.18

Consuming the largest meals and overall eating window in the morning and early afternoon, while keeping evening intake lighter, appears to offer a measurable metabolic advantage.2,17 When evening meals are unavoidable, they should remain light, low-GI, and fiber-rich to minimize postprandial glucose levels.

A balanced meal structure may include non-starchy vegetables, legumes, lean proteins such as fish or tofu, and small portions of whole grains. Emphasizing tryptophan- and magnesium-containing foods such as yogurt, nuts, and leafy greens may also support sleep quality without overloading the system during its lowest metabolic-efficiency phase.4

Early TRE (eTRE), with an eating window ending by mid-afternoon, consistently improves cellular capacity to use glucose and lipids and may lower blood pressure. Notably, eTRE improves glycemic control more effectively than late TRE, suggesting an inherent benefit of circadian alignment.19

For most individuals, including shift workers, adapting to challenging schedules, prioritizing calorie consumption at earlier times, and reducing nighttime intake can lead to meaningful metabolic improvements.18,19

References

- Raji, O. E., Kyeremah, E. B., Sears, D. D., et al. (2024). Chrononutrition and Cardiometabolic Health: An Overview of Epidemiological Evidence and Key Future Research Directions. Nutrients 16(14); 2332. DOI: 10.3390/nu16142332. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/14/2332.

- Mercedes, N., Annunziata, G., Galasso, M., et al. (2024). Chrononutrition and Energy Balance: How Meal Timing and Circadian Rhythms Shape Weight Regulation and Metabolic Health. Nutrients 17(13); 2135. DOI: 10.3390/nu17132135. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/13/2135.

- Gu, C., Brereton, N., Schweitzer, A., et al. (2020). Metabolic Effects of Late Dinner in Healthy Volunteers - A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 105(8); 2789. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa354. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/105/8/2789/5855227.

- Zuraikat, F. M., Wood, R. A., Barragán, R., & St-Onge, P. (2021). Sleep and Diet: Mounting Evidence of a Cyclical Relationship. Annual Review of Nutrition 41(309). DOI: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-120420-021719. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-nutr-120420-021719.

- Huda, A., Majid, N. B. A., Chen, Y., et al. (2024). Exploring the ancient roots and modern global brews of tea and herbal beverages: A comprehensive review of origins, types, health benefits, market dynamics, and future trends. Food Science & Nutrition 12(10); 6938. DOI: 10.1002/fsn3.4346, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/fsn3.4346

- Gardiner, C., Weakley, J., Burke, L. M., et al. (2023). The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 69. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079223000205.

- Fenne, K. T., Clauss, M., Schäfer Olstad, D., et al. (2022). An Acute Bout of Endurance Exercise Does Not Prevent the Inhibitory Effect of Caffeine on Glucose Tolerance the following Morning. Nutrients 15(8); 1941. DOI: 10.3390/nu15081941. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/8/1941.

- Gardiner, C., Weakley, J., Burke, L. M., et al. (2025). The effect of alcohol on subsequent sleep in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 80, 102030. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2024.102030. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079224001345?via%3Dihub.

- Strüven, A., Schlichtiger, J., Hoppe, J. M., et al. (2024). The Impact of Alcohol on Sleep Physiology: A Prospective Observational Study on Nocturnal Resting Heart Rate Using Smartwatch Technology. Nutrients 17(9) 1470. DOI: 10.3390/nu17091470. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/9/1470.

- Almoosawi, S., Vingeliene, S., Gachon, F., et al. (2018). Chronotype: Implications for Epidemiologic Studies on Chrono-Nutrition and Cardiometabolic Health. Advances in Nutrition 10(1); 30-42. DOI: 10.1093/advances/nmy070. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2161831322012844

- Mason, I. C., Qian, J., Adler, G. K. et al. (2020). Impact of Circadian Disruption on Glucose Metabolism: Implications for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 63; 462–472. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-019-05059-6. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-019-05059-6.

- Yan, L., Rust, B. M., & Palmer, D.G. (2024). Time-restricted feeding restores metabolic flexibility in adult mice with excess adiposity. Frontiers in Nutrition 11. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1340735. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1340735/full

- Colonnello, E., Libotte, F., Masi, D. et al. (2025). Eating behavior patterns, metabolic parameters, and circulating oxytocin levels in patients with obesity: an exploratory study. Eating and Weight Disorders 6. DOI: 10.1007/s40519-024-01698-w. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40519-024-01698-w

- da Cunha, N.B., Teixeira, G.P., Rinaldi, A.E.M., et al. (2023). Late meal intake is associated with abdominal obesity and metabolic disorders related to metabolic syndrome: A chrononutrition approach using data from NHANES 2015–2018. Clinical Nutrition Journal 42; 1798-1805. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.08.005. https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(23)00256-X/fulltext.

- Palomar-Cros, A., Andreeva, V. A., Fezeu, L. K., et al. (2023). Dietary Circadian Rhythms and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in the Prospective NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Nature Communications 14. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-43444-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-43444-3

- Dashti, H. S., Jansen, E. C., Dixit, S., et al. (2025). Advancing Chrononutrition for Cardiometabolic Health: A 2023 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop Report. Journal of the American Heart Association 14(9). DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.124.039373. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.124.039373

- Fernandes-Alves, D., Teixeira, G. P., Guimarães, K. C., & Crispim, C. A. (2025). Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Time-Restricted Eating with and Without Caloric Restriction for Weight Loss. Nutrition Reviews 29. DOI: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaf053. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/nutrit/nuaf053/8121825

- Liu, J., Yi, P., & Liu, F. (2023). The Effect of Early Time-Restricted Eating vs Later Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Metabolic Health. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 108; 1824–1834. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgad036. https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/108/7/1824/7005458?login=false.

- Yu, Z. & Ueda, T. (2025). Early Time-Restricted Eating Improves Weight Loss While Preserving Muscle: An 8-Week Trial in Young Women. Nutrients 17. DOI: 10.3390/nu17061022. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/6/1022.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 16, 2025