Introduction

Ethnobotanical and historical use

Phytochemical composition

Scientific evidence in reproductive health

Safety, contraindications, and guidelines

Emerging areas of interest

Areas for future research

References

Further reading

Raspberry leaf tea is traditionally used to support pregnancy and women’s reproductive health, with studies examining its phytochemicals, safety, and possible benefits. Evidence remains limited, highlighting the need for further research.

Image Credit: teatian / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: teatian / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

This article reviews the historical and traditional applications of raspberry leaf tea (RLT), examines its phytochemical composition, and evaluates the current scientific research on its potential role in reproductive health, especially during pregnancy and childbirth.1,2

Ethnobotanical and historical use

RLT has been traditionally used across cultures, including Indigenous North American and European folk medicine, particularly for female reproductive and maternal health. Historically, herbalists used the leaves and young shoots of Rubus idaeus for various conditions, including menstrual cramps, gastrointestinal issues, and to support or facilitate labor rather than directly induce contractions.

Often consumed during late pregnancy, RLT is traditionally believed to support uterine tone, which may lead to more efficient contractions, shorter labor, and fewer interventions like cesarean sections or assisted deliveries. Some herbal traditions also suggest RLT may help regulate menstrual cycles and ease discomfort, although these effects are not confirmed by clinical trials.2

Throughout the world, many naturopaths continue to incorporate RLT into pregnancy-support regimens, citing potential benefits like reduced risk of conditions such as preeclampsia, preterm or prolonged labor, and postpartum hemorrhage. However, due to limited data, healthcare providers often recommend limiting its use to the second and third trimesters to ensure safety.2

Phytochemical composition

Raspberry leaf contains a diverse array of bioactive constituents that contribute to its reputed health benefits. Key compounds include flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, and catechin, tannins, phenolic acids, and ellagitannins, particularly ellagic acid, which is a notable polyphenol present in RLT.

The raspberry leaf contains fragrine, an alkaloid that is traditionally believed to improve uterine firmness and contractions, though its mechanism in humans remains unclear. RLT also provides essential vitamins A, C, E, K, and B-complex, citric and malic acids, as well as minerals like calcium, magnesium, iron, and potassium. These nutrients contribute to the nutritional value and potential therapeutic effects associated with RLT.1,4

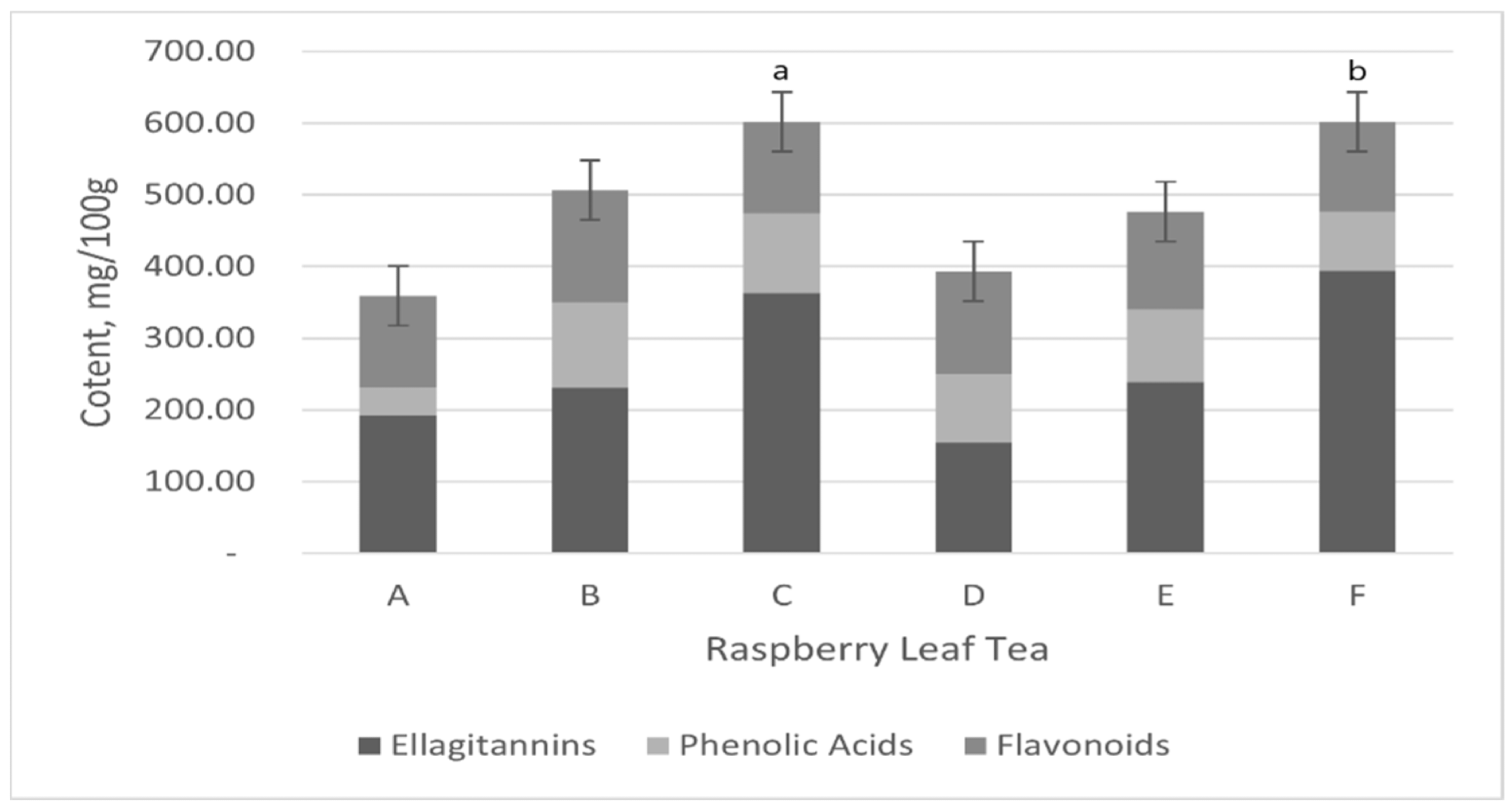

Comparative analysis of total polyphenol content in different raspberry leaf tea samples. Light grey: flavonoids; black: ellagitannins; white: phenolic acids, p < 0.001 (mean ± S.D., n = 3). Mean concentrations of polyphenol, flavonoids, ellagitannins, and phenolic acids in teas from different countries. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Samples include tea from Croatia (A), Bulgaria (B), the United Kingdom (C), Belgium (D), Germany (E), and Poland (F). Bars sharing the same letter indicate significant differences (p < 0.001 vs. all sample teas marked “a”; p < 0.05 vs. A, B, D, and E marked “b”).1

Comparative analysis of total polyphenol content in different raspberry leaf tea samples. Light grey: flavonoids; black: ellagitannins; white: phenolic acids, p < 0.001 (mean ± S.D., n = 3). Mean concentrations of polyphenol, flavonoids, ellagitannins, and phenolic acids in teas from different countries. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Samples include tea from Croatia (A), Bulgaria (B), the United Kingdom (C), Belgium (D), Germany (E), and Poland (F). Bars sharing the same letter indicate significant differences (p < 0.001 vs. all sample teas marked “a”; p < 0.05 vs. A, B, D, and E marked “b”).1

RLT is often compared to other herbal teas during pregnancy, such as peppermint for nausea relief, ginger to prevent nausea and vomiting, chamomile for relaxation, and fennel to improve digestion. Despite these potential benefits, peppermint tea has been reported in some sources to induce menstrual flow in early pregnancy, although strong human evidence is lacking, whereas ginger can cause dry mouth, may increase bleeding risk, and interact with drugs like insulin and metformin.5

Chamomile tea intake has been linked in some case reports and animal studies to miscarriage, preterm labor, and fetal circulation issues. Fennel, though supportive of lactation and digestion, exhibits estrogenic activity, with several reports suggesting fetal toxicity and potential drug interactions.

In contrast, RLT is a nutrient-rich beverage that is generally considered safer than other tea alternatives, particularly in the second and third trimesters, due to its traditional role in promoting uterine health and toning. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of RLT intake during pregnancy.5

RLT exhibits significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that have been confirmed through free radical scavenging assays. Other reported pharmacological activities have been based on in vitro observations and include antimicrobial, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, and chemopreventive effects.1,4

Scientific evidence in reproductive health

Preclinical studies report stimulant and relaxant effects of raspberry leaf on uterine smooth muscle, depending on timing and context. Late-pregnancy rat uteri models experience increased contractions following RLT intake, whereas guinea pigs exhibit relaxant or spasmolytic effects.

Although clinical research on RLT remains limited and largely observational, existing studies suggest encouraging outcomes in pregnancy and childbirth. Women who consumed RLT during pregnancy in some observational studies were more likely to experience fewer medical interventions during labor.

Reported benefits include lower rates of cesarean sections, assisted birth, artificial rupture of membranes (AROM), labor augmentation, and epidural use. RLT consumption also increases the likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth, with some studies reporting approximately 4.5 vaginal deliveries for every one non-vaginal birth, though this comes from a single observational study and should be interpreted cautiously.

RLT consumption may also reduce the duration of second-stage labor by approximately 10 minutes in some reports, although statistical significance is not consistent across studies, and improve neonatal outcomes, including higher APGAR scores and reduced neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions.2,6

Importantly, these observations are based on studies with numerous methodological weaknesses, including small sample sizes, lack of randomization, inconsistent dosing, and varied gestational timing. RLT doses ranged from one to six cups daily, with this intervention initiated anywhere between eight and 38 weeks, thereby making it difficult to standardize recommendations.

Image Credit: Halfpoint / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Halfpoint / Shutterstock.com

Safety, contraindications, and guidelines

RLT is generally considered safe to consume during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy in moderate amounts under medical supervision. Due to its potential uterotonic effects, most healthcare professionals advise against consuming RLT during the first trimester. Timing and dosage should be individualized, as pharmacological effects vary based on the preparation method, extraction technique, tissue type, baseline muscle tone, and pregnancy status of the uterus or uterine tissue.3,7

Animal studies have reported toxic effects of raspberry leaves when administered in high doses or through intraperitoneal or intravenous injection. In these cases, central nervous system stimulation and cardiovascular toxicity were observed, including cyanosis and heart dilation in mice, and convulsions and death in chicks.3,7 Importantly, these observations were obtained from studies using non-oral routes and high concentrations, which do not reflect typical human consumption. In fact, clinical research on oral RLT during pregnancy indicates a favorable safety profile. 2,3

Nevertheless, RLT has shown in some in vitro studies the ability to inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes, which alter the metabolism of drugs. RLT also exhibits possible mild hypoglycemic effects and may interfere with iron absorption, thereby warranting caution among individuals with diabetes or anemia.6,8

Emerging areas of interest

Traditionally used to alleviate menstrual cramps, regulate heavy bleeding, and ease menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats, RLT is also promoted in herbal practice for fertility support. The uterine-toning properties of RLT may contribute to reduced menstrual discomfort and premenstrual symptoms.9

RLT is rich in antioxidants, including vitamin C, polyphenols, magnesium, and folate, all of which are nutrients that may support reproductive tissue health. Although most evidence remains preclinical, folate content is particularly relevant for women planning pregnancy. During menopause, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of RLT have been suggested to provide natural support for reducing symptoms like hot flashes and mood fluctuations, though clinical confirmation is lacking.9

Areas for future research

Despite widespread traditional use, RLT lacks robust scientific evidence. Thus, future research must prioritize understanding its pharmacokinetics, especially the absorption, metabolism, and excretion of active compounds such as ellagic acid and flavonoids. Future studies are also needed to clarify the mechanisms of action, particularly regarding uterotonic effects and labor modulation.10

Current assumptions about the uterotonic and anti-inflammatory properties of RLT remain largely unverified. Standardization is also a significant concern, as product composition varies by source and preparation, which influences safety and efficacy.

Well-designed clinical trials are warranted to establish dosage guidelines, assess potential herb-drug interactions, and ensure consistent formulations. Advancing research in these areas would facilitate safe and evidence-based use of RLT in reproductive health.10

References

- Alkhudaydi, H. M., Muriuki, E. N., & Spencer, J. P. (2025). Determination of the Polyphenol Composition of Raspberry Leaf Using LC-MS/MS. Molecules, 30(4), 970. DOI: 10.3390/molecules30040970, https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/30/4/970

- Bowman, R.L., Taylor, J. & Davis, D.L. (2024). Raspberry leaf (Rubus idaeus) use in pregnancy: a prospective observational study. BMC Complement Med Ther., 24, 169. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-024-04465-7, https://bmccomplementmedtherapies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-024-04465-7

- Bowman, R., Taylor, J., Muggleton, S. et al. (2021). Biophysical effects, safety, and efficacy of raspberry leaf use in pregnancy: a systematic integrative review. BMC Complement Med Ther., 21, 56. DOI: 10.1186/s12906-021-03230-4, https://bmccomplementmedtherapies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-021-03230-4

- Luo, T., Chen, S., Zhang, H., Jia, S., & Wang, J. (2020). Phytochemical composition and potential biological activities assessment of raspberry leaf extracts from nine different raspberry species and raspberry leaf tea. Journal of Berry Research, 10(2), 295-309. DOI: 10.3233/JBR-190474, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3233/JBR-190474

- Bebitoglu, B. T. (2020). Frequently Used Herbal Teas During Pregnancy - Short Update. Medeniyet Medical Journal, 35(1), 55. DOI: 10.5222/MMJ.2020.69851, https://medeniyetmedicaljournal.org/jvi.aspx?pdir=medeniyet&plng=eng&un=MEDJ-69851&look4=

- Makaji E, Ho SH, Holloway AC, Crankshaw DJ. (2011). Effects in rats of maternal exposure to raspberry leaf and its constituents on the activity of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the offspring. Int J Toxicol.;30(2):216–24. DOI: 10.1177/1091581810388307, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1091581810388307

- Zheng, J., Pistilli, M.J., Holloway, A.C. et al. (2010). The Effects of Commercial Preparations of Red Raspberry Leaf on the Contractility of the Rat’s Uterus In Vitro. Reprod. Sci., 17, 494–501. DOI: 10.1177/1933719109359703, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1177/1933719109359703

- Cheang KI, Nguyen TT, Karjane NW, Salley KE. (2016). Raspberry leaf and hypoglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol., 128(6):1421–4. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001757, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27824754/

- Alinia-Ahandani, Farjad Rafeie, Zahra Alizadeh-Tarpoei, Sahebe Hajipour, Zeliha Selamoglu, and Elisfena Canan Alp Arici. (2022). Overview on raspberry leaves and cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides) as partus preparatory. Central Asian Journal of Plant Science Innovation, 2(2):54-61. DOI: 10.22034/CAJPSI.2022.02.02, https://www.cajpsi.com/article_167053.html

- Socha, M. W., Flis, W., Wartęga, M., Szambelan, M., Pietrus, M., & Kazdepka-Ziemińska, A. (2023). Raspberry Leaves and Extracts-Molecular Mechanism of Action and Its Effectiveness on Human Cervical Ripening and the Induction of Labor. Nutrients, 15(14), 3206. DOI: 10.3390/nu15143206, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/14/3206

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 8, 2025