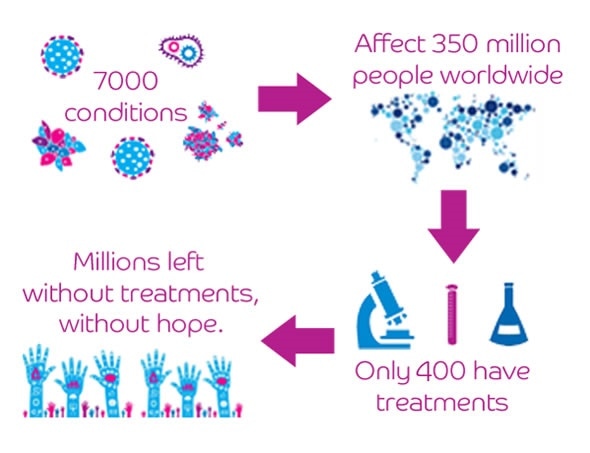

However, there are over 7000 known rare diseases, a number that keeps growing. Clearly there is a huge unmet need for rare disease treatments.

The rarity of patients with a specific rare disease and their broad dispersal around the globe makes research exceptionally challenging.

Firstly, there is so little known about many rare diseases, that securing research interest is a real challenge. Even if that interest exists, building a network of patients in whom to study the disease can prove desperately hard, particularly without strong patient engagement.

Funding is often hard to secure for such research as the rarity of a disease is often falsely equated with its importance.

Finally, the delivery of clinical trials is very challenging in small, dispersed populations, from both logistical and statistical perspectives.

Even if these challenges are overcome, many businesses struggle to build a financially viable model for the production and distribution of new treatments for rare disease patients.

In general the larger rare disease populations receive research interest, often supported by their own patient groups, but many new treatments are sold at exceptionally high prices. This leaves many rare disease patients with little hope for a cure.

What is off-label prescription of drugs and how common is it with regards to rare diseases?

With so few available treatments, doctors are often left with a difficult choice - to leave rare disease patients untreated, or to prescribe drugs that are not licenced for the specific rare disease but which they think could benefit the patient. This is off-label prescription.

In many cases such drugs will be prescribed to manage specific symptoms for which they are commonly used in other conditions. Less frequently drugs may be prescribed off-label based on knowledge and understanding of the underlying condition, with the hope of treating the condition as a whole.

Off-label prescription is actually a very common practice in medicine, with some estimating that around 30% of all prescriptions are off-label. In otherwise untreatable rare diseases, the justification for such use is certainly compelling.

Why are there elements of uneasiness around off-label prescription?

On-label use is based on the results of controlled clinical testing and a clear quantifiable effect of the drug in a large population. In contrast, there is no requirement for such evidence in off-label use. This isn’t to say that all off-label use lacks evidence but it does lack regulation, which can lead to concerns for patient safety.

Clearly, responsible off-label use should be based on a clear hypothesis or existing evidence of effect. Furthermore, it should be accompanied by careful monitoring and reporting, and be done with the patient’s consent.

When no other treatment option exists, such responsible off-label use can provide crucial hope and health benefits to patients, and lead to vital clinic driven healthcare innovation.

What is drug repurposing?

Drug repurposing is like recycling - essentially it takes existing drugs, licensed for one illness, and finds new illnesses which they can treat. This effect should be demonstrated in a clinical trial, providing strong evidence for a new use.

In general, the term repurposing refers to the identification of new uses for generic drugs: those that are no longer patent protected.

Drug repurposing is faster and cheaper than conventional drug discovery, and subsequently has great potential to provide new treatments for rare diseases.

How is Findacure helping to find treatments for rare diseases?

Findacure is setting up a generic drug repurposing programme for rare diseases. We are working to identify viable drug repurposing projects, which have an existing evidence base suggesting a disease modifying effect in a rare disease.

Once identified, Findacure will then establish collaborative project teams including patient groups, clinicians, and researchers, who can deliver clinical trials to test the efficacy of these drugs in the new rare disease patient population.

To fund this work Findacure is trying to establish a new funding mechanism, called a social impact bond, which aims to use social finance and health system savings to fund drug repurposing research.

What are the main challenges when running clinical trials for rare diseases and how can they be overcome?

The biggest challenge of any clinical trial in a rare disease is the recruitment of a large number of patients, in order to generate statistically meaningful results from your trial.

At Findacure, we strongly believe that this challenge can be overcome by involving patient groups in trial planning and design from the outset.

The rare disease world is unusual, in that there are many active and informed patient groups, committed to securing treatments for their patients. By bringing patient groups on board early, trials can be designed to suit patient needs, helping to ensure those that join a trail stay to the end.

The patient group provides a vital connection between the clinical team and patients themselves, smoothing patient recruitment, and passing vital information about trial progress to the patient. This helps them to feel truly involved in the research effort.

Can you please outline Findacure’s new approach to funding trials using Social Impact Bonds?

A social impact bond is another way to secure investment into drug development. We aim to secure enough investment to fund ten generic drug repurposing clinical trials. These will all be designed to test the efficacy of the existing drug in a rare disease.

The crucial part of the model is how we generate investment returns. Conventionally, money is made through the sale of the drug - this is not our aim. Instead we are aiming to repurpose drugs for diseases that are currently expensive to manage for the NHS.

If this is the case, providing a new disease modifying drug at the low price of a generic will save the NHS money, as well as improve patient health. We are seeking to access some of these savings from the NHS. These savings will be used to pay back the initial investment in all of the trials.

If enough trials are successful, we should have enough money left over to fund further repurposing trials.

How do you quantify the current cost to the NHS of a specific rare disease and the amount the repurposed drug would cost?

The cost of rare diseases is currently poorly understood, something that our project will hopefully begin to change.

When we identify a potential repurposing project we work with our clinical partners, as well as Costello Medical Consulting Ltd, to build an in-depth cost of illness model for the rare disease.

First we construct a treatment pathway for patients, which represents current NHS practise for managing the disease. As many rare diseases are treated at specialist centres, such pathways are representative for the majority of patients.

Using this pathway, we can price the individual stages of treatment based on government data about healthcare costs, the price of drugs, and internal hospital financial data.

The final challenge is to identify the likelihood of patients receiving certain treatments or their disease progressing at certain times. This data is the hardest to obtain, but can be derived from either expert clinical opinion or healthcare records.

With all of these components a model can be produced which estimates NHS expenditure on the rare disease. Furthermore, we then estimating the potential savings that could be made to the NHS through the use of a repurposed generic drug.

The cost of the repurposed drug is therefore crucial to the model. A low price will ensure higher savings. In our current social impact bond model, we are working to produce high quality clinical trials, which when published will provide an evidence base for off-label prescription of the repurposed drug to rare disease patients. Such off-label use means that the drug can be delivered at its current generic cost, which will be invariably lower than an on-label product.

Why are you only targeting generic drugs?

For two reasons. Firstly, due to the difficulty of securing intellectual property on generic drugs and the small size of rare disease patient populations, the pharmaceutical industry is highly unlikely to work on generic drug repurposing projects for rare diseases - there is no financial incentive for them to do so. We think this market failure needs to be addressed, and our social impact bond model can do that.

Secondly, the prescription of existing generic drugs to rare disease patients on an off-label basis would ensure the low price of the drug. This maximises the potential savings to the NHS and gives us the best chance to generate a large return on our initial investment.

Has the NHS been supportive of Findacure’s approach?

Funding drug development using social finance is a new idea, but clearly appeals to the two overriding aims of the NHS: to deliver improved health to patients and to do so at a lower financial cost.

We have received support from the NHS for our model and they are keen to see the idea developed further. We are currently working with them to prove the concept of a rare disease drug repurposing social impact bond, with the aim of securing their support to commission the project in the future.

What do you think the future holds for patients with rare diseases?

In the last few years there has been a dramatic change in the rare disease world. Rare Disease Day, the last day of February, has grown to a global event.

Patient groups are becoming increasingly active and professional. Their value is beginning to be recognised by the pharmaceutical industry, helping patient groups to secure involvement in drug development and delivery.

The rise of genomics, and the personalised medicine paradigm, is helping to drive diagnosis, as well as splitting many common diseases into multiple smaller ones.

All this means that industry and governments have to find new ways to deliver tailored drugs to smaller populations in an affordable and sustainable manner.

There is a long way to go on this journey, but hopefully it will lead to an increased role for rare disease patients in the drug development process and an increased level of treatment discovery for their diseases.

The future for rare disease patients is more hopeful than it has ever been, but it will require all of their effort and determination to bring their hopes to fruition.

Findacure’s social impact bond aims to provide a new route for such patient groups to deliver these treatments, helping as many rare disease groups as possible to blaze a trail for the whole rare disease community.

Where can readers find more information?

Readers can find out more about our work on our website - www.findacure.org.uk - by subscribing to our mailing list, or by following us on Facebook and Twitter. If you have specific questions or ideas, please contact Rick at [email protected].

About Dr Richard Thompson

Dr Richard Thompson is the Scientific Officer for Findacure: a UK charity building the rare disease community to drive research and develop treatments.

Dr Richard Thompson is the Scientific Officer for Findacure: a UK charity building the rare disease community to drive research and develop treatments.

He secured his PhD from the University of Cambridge in 2014, and joined Findacure shortly after. As Scientific Officer, he is responsible for engaging with the scientific community about the importance of rare disease research and leads Findacure’s drug repurposing programme.

The rare disease drug repurposing social impact bond is the brain child Dr Nick Sireau, one of Findacure’s founders, and Dr Bruce Bloom, President and CSO of US charity Cures Within Reach. Rick leads its development and is excited to complete Findacure’s proof of concept study, with the aim of driving the project to delivery in the coming year.