Sep 20 2018

Inflammation, long considered a dangerous contributor to atherosclerosis, actually plays an important role in preventing heart attacks and strokes, new research from the University of Virginia School of Medicine reveals.

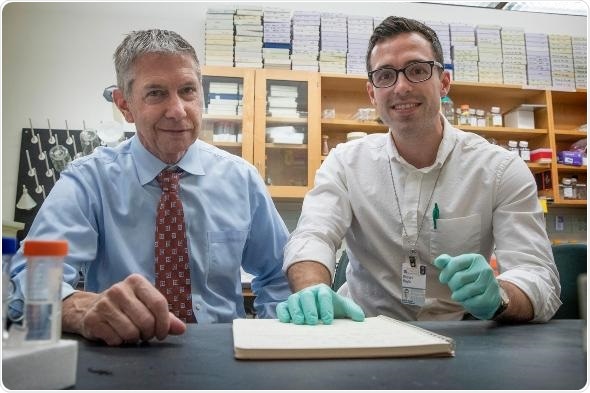

Researchers Gary Owens (left) and Ricky Baylis and colleagues have found a positive role for inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions inside the blood vessels.

The work also raises an important caution about a high-profile drug, canakinumab, being tested to treat advanced atherosclerosis. The drug would need to be prescribed only to a select group of patients, UVA’s research suggests.

Inflammation and Atherosclerosis

In medicine, inflammation is often viewed as harmful, something best suppressed with drugs. Healthcare company Novartis, for example, has recently tested a potent anti-inflammatory drug, canakinumab, in hopes of benefiting patients with advanced atherosclerosis who have previously suffered a heart attack.

The new study from the laboratory of UVA’s Gary Owens, PhD, reveals, however, that inflammation plays a key role in maintaining the stability and strength of atherosclerotic lesions inside the blood vessels. Blocking too much of a key inflammatory mediator resulted in to weaker lesions more likely to rupture, because the absence of inflammation leads the body to conclude, wrongly, that the repair has been completed. “We believe that globally suppressing inflammation gives the tissue a false sense of inflammation resolution,” said Ricky Baylis, an MD/PhD student in the Owens lab and major contributor to the study. “And by removing this key danger signal, you appear to be taking away the good guys prematurely.”

That means that doctors would need to be highly selective in prescribing canakinumab for atherosclerosis, should it be approved for that purpose by the federal Food and Drug Administration, said Owens, director of UVA's Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center.

“What our data suggests is that you need to be extremely cautious in starting to give this drug more broadly to lower-risk patients,” he said. “This is not a drug that should be prescribed broadly like statins, because we believe our data suggests that if you suppress inflammatory response without first removing or reducing the cause of the inflammation, which is lipids, necrotic tissue debris and other plaque components, that this could become dangerous and have unintended consequences. … If you give it to the wrong person, it could do the opposite of what you intended.”

That’s an important caveat because many doctors are eager for a drug to help patients with advanced atherosclerosis who are at high risk. Novartis’ drug testing, for example, seeks to benefit “a group of patients that, despite our best therapies, still have an elevated risk for major cardiovascular events,” Owens said. “There is really no drug for them to take.”

Creating Safer Drugs

Owens has an ongoing partnership with Novartis, and he noted that the collaboration of companies such as Novartis with scientists at academic universities helps make for safer, more effective medicines.

“I hope people will look at the CANTOS clinical trial and our study and find encouragement in the fact that there are scientists in the lab working day and night for years trying to better understand the effects of this intervention strategy,” Owens said. “Our mouse studies allow us to generate hypotheses that can then be tested in humans, to gain a better understanding of what happens when we give these types of drugs. And it’s likely that with that knowledge we'll be able to better design drugs that are more effective and safer by targeting the bad parts of inflammation but retaining or enhancing the good parts of inflammation that increase the stability of atherosclerotic lesions.”

Rapidly Changing Lesions Suggests Both Promise and Peril

In addition to a more nuanced understanding of inflammation in atherosclerosis, the study suggests that our lesions are more susceptible to change – both for better or for worse. The traditional view of atherosclerotic lesions is that they’re dormant – that they remain largely unchanged after the body creates them to seal off accumulations of dangerous material inside the blood vessels. In that sense, the fibrous caps covering the lesions have been viewed like patches on a tire. But UVA’s study finds that the caps change significantly over time and can change quite quickly. This became apparent when treatment with the anti-inflammatory therapy rapidly reduced fibrous cap integrity. The finding suggests that doctors and patients have a much greater opportunity to strengthen the caps to prevent heart attacks and strokes.

“This study seems to indicate that the fibrous cap, as a structure, is actually much more plastic than previously thought,” Baylis said. “This can be seen as an obstacle but also an opportunity, suggesting that proper treatment and lifestyle changes can rapidly stabilize risky lesions but also that poor management – even for short periods – may have the opposite effect.”