Albeit pregnancy is generally considered a significant risk factor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and more severe coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outcomes, a recent study by a multinational team of researchers shows that symptoms are generally comparable between pregnant and non-pregnant cohorts of women – with the exception of gastrointestinal symptoms. This paper is currently available on the medRxiv* preprint server.

As soon as the COVID-19 pandemic started, pregnant women were immediately considered as a vulnerable group for increased morbidity and mortality, based on the theoretical risks of relative immunosuppression during pregnancy, as well as previous studies of smaller coronavirus outbreaks.

But more steadfast conclusions needed more robust data. Since their introduction, smartphone and web-based applications for population-based syndromic surveillance became citizen science tools that greatly facilitated the swift acquisition of extensive epidemiological data as this pandemic evolved.

Consequently, researchers from the United Kingdom, United States and Sweden (led by Dr. Erika Molteni from the King's College London) decided to use these data in order to test the hypothesis whether pregnant women in the community differ in their COVID-19 symptoms profile and disease severity when compared to their non-pregnant counterparts.

A bright example of participatory epidemiology

This study used a participatory epidemiology approach by leveraging two remote cohorts, enabling rapid assessment of COVID-19 in pregnancy. More specifically, the discovery cohort was drawn from 400,750 women from the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States who self-reported symptoms and events via their smartphones, comprising 79 pregnant ones who tested positive.

On the other hand, the replication cohort was drawn from 1,344,966 women from the United States and consisted of cross-sectional self-reports samples from the social media active user base. In this cohort, 162 pregnant women tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

In short, the longitudinal nature of the discovery dataset opened the door for the comparison of disease duration, time from onset to symptom peak, as well as hospitalization specificities between pregnant and non-pregnant women, prospectively.

The study aimed to compare frequencies of symptoms and events – including self-reported SARS-CoV-2 testing and differences between pregnant and non-pregnant women who recovered in the community and who were hospitalized. Multivariable regression methods were used to explore disease severity and comorbidity effects.

Kindred disease trajectories

In this study, pregnant women reported more frequent testing for the presence of SARS-CoV-2, albeit they generally did not experience a more severe disease course. In other words, disease trajectories in these two groups were similar, while the time from disease onset to symptom peak was only slightly longer in pregnant than non-pregnant women (i.e., 2.8 vs. 2.2 days).

Conversely, gastrointestinal symptoms were significantly different in pregnant and non-pregnant women presenting with poor outcomes, with decreased skipped meals in the discovery cohort and increased nausea/vomiting in the replication cohort.

"Pre-existing lung disease was most closely associated with the severity of symptoms in pregnant hospitalized women," say study authors. "Heart and kidney diseases and diabetes were additional factors of increased risk," said study authors.

In addition, specific cardiopulmonary symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, and persistent cough were more frequently observed among pregnant women who were hospitalized, pointing towards the conclusion that cardiopulmonary symptoms are a significant discriminant for hospitalization.

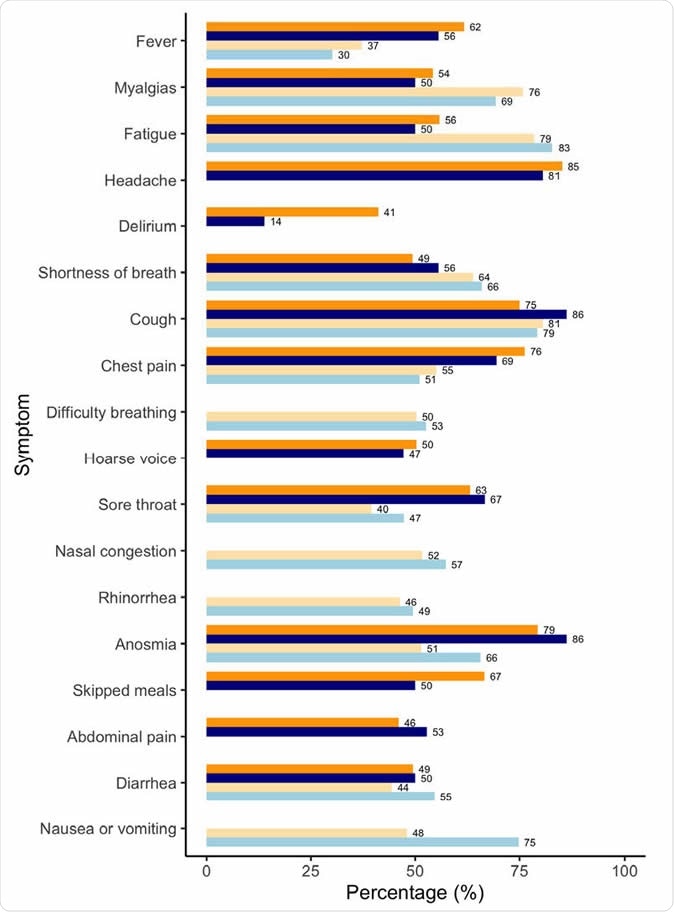

Comparison of symptoms presentation in the discovery (DC) and replication (RC) cohorts. Results refer to non-pregnant (orange) and pregnant (blue) women tested positive and suspected positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who required hospitalization (in DC, darker shade) or were seen at the hospital (RC, lighter shade). Results are reported as age-standardized percentage of women reporting each symptom in each subcohort.

Clinical and research implications

Even though pregnancy is widely considered as a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection and more severe outcomes, and was undoubtedly associated with a higher propensity for testing, symptom profile and severity in these community-based cohorts were comparable to those observed among non-pregnant women – with the exception of gastrointestinal symptoms.

However, pregnant women with prominent cardiopulmonary symptoms or pre-existing lung disease may indeed necessitate special attention during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In short, lung disease showed the strongest impact on disease severity in pregnancy.

"Clinicians should be more vigilant with pregnant women who have pre-existing health conditions, prominent respiratory symptoms or a higher severity index - as is the case in the general population," caution study authors in this medRxiv study.

In any case, further studies that specifically target high-risk pregnancies and outcomes across the three trimesters are warranted, in order to improve outcome definition in this population. Likewise, there is a need to interpret severity indices and hospitalization rates in light of the policy changes, which may depend on the context or country.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Molteni, E. et al. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection in pregnant women: characterization of symptoms and syndromes predictive of disease and severity through real-time, remote participatory epidemiology. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.17.20161760.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Molteni, Erika, Christina M. Astley, Wenjie Ma, Carole H. Sudre, Laura A. Magee, Benjamin Murray, Tove Fall, et al. 2021. “Symptoms and Syndromes Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Severity in Pregnant Women from Two Community Cohorts.” Scientific Reports 11 (1): 6928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86452-3. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-86452-3.