While UK families cherish the togetherness of takeaway nights, new research uncovers surprising trends about who is most likely to indulge, challenging assumptions about income, convenience, and the real meaning of family meals.

Study: “Takeaway Night”: Understanding UK Families’ Consumption of Takeaway Food for Family Mealtimes. Image Credit: Lucky Business / Shutterstock

Study: “Takeaway Night”: Understanding UK Families’ Consumption of Takeaway Food for Family Mealtimes. Image Credit: Lucky Business / Shutterstock

In a recent article published in the journal Appetite, researchers at the University of Reading, UK, investigated how families incorporate takeaway food – defined as hot food prepared away from home, collected or delivered, and eaten at home as part of a shared family meal – into shared family mealtimes. They aimed to understand the emotional and social benefits of eating together as a family that might counterbalance, though this remains unproven, the poor nutritional quality of their meals.

They found that almost all families (96%) reported at least occasional takeaway use, although most had takeout less than once a week. Parents viewed it positively as an enjoyable, convenient treat that fostered family connection. While most parents expressed positive views, some also acknowledged guilt or concern about the healthiness of takeaways. Parents from low-income households and the most deprived neighborhoods were more likely to consume takeaways frequently. However, this pattern was non-linear: high-income households showed a similar frequency to low-income ones, suggesting complex socio-economic influences.

Background

In today’s food environment, families have widespread access to food that is not prepared at home. These options fall under the UK’s broader definition of takeaway food, which typically refers to hot meals collected or delivered for consumption at home.

However, strong evidence suggests that takeaway food is nutritionally poor, being high in saturated fat, salt, and sugar. It is associated with higher calorie intake, increased body fat, and risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The growing availability and consumption of takeaway food is considered a factor in the obesity epidemic.

Despite these concerns, family mealtimes, regardless of the food served, are associated with numerous positive developmental outcomes. Research suggests that regular family meals are linked to enhanced mental health and well-being in children and adolescents, as well as decreased involvement in high-risk behaviors.

Although preparing meals can be stressful for parents, they generally value the shared experience and often prioritize health in their meal planning. In this context, takeaway food may reduce conflict and ease preparation while still promoting family togetherness.

Yet, it remains unclear whether these social benefits can counterbalance the nutritional drawbacks. This study, therefore, aimed to explore how often and why UK families consume takeaway food for family mealtimes, and under what circumstances.

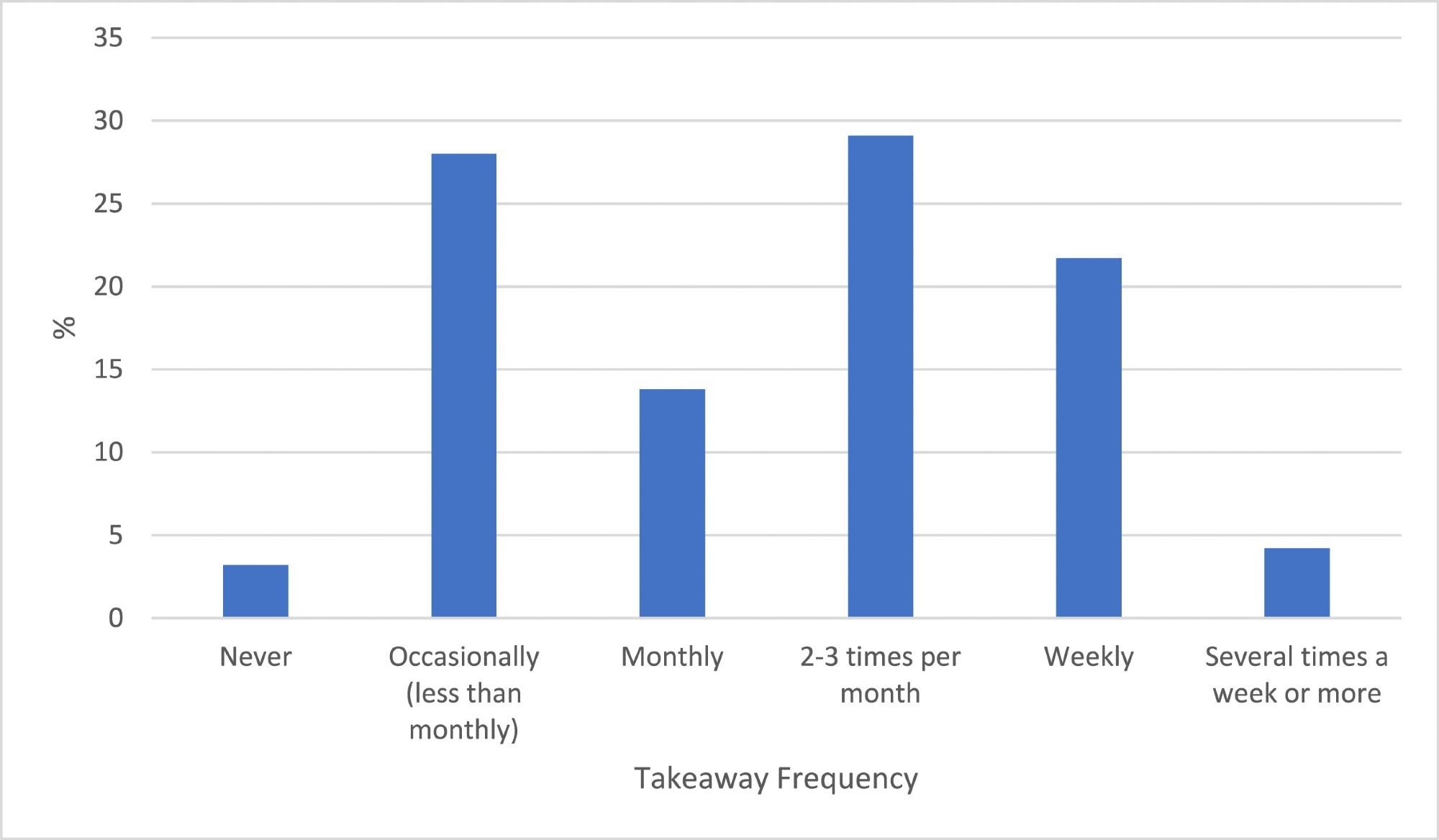

Frequency Takeaway Food Consumed for Family Mealtimes (N = 189)

Frequency Takeaway Food Consumed for Family Mealtimes (N = 189)

About the study

This cross-sectional study employed an online survey to investigate how UK families utilize takeaway food for family meals, focusing on parents of children aged 18 years or younger residing in the UK.

Recruitment combined broad outreach via social media and parenting forums with focused efforts to reach underrepresented groups, such as single parents, ethnic minorities, and low-income households, through targeted platforms and community noticeboards.

Participants who accessed the survey were first presented with study information and definitions of key terms, such as "takeaway food" and "family mealtime." The survey included two main components. The questionnaire, developed by the researchers, consisted of five closed-ended and six open-ended questions assessing frequency, timing, participants, and reasons for takeaway use. It also captured decision-making processes related to ordering and consumption settings. A second questionnaire collected socio-demographic data.

Data quality was ensured through multiple checks, including attention checks, required open-ended responses, and time analysis.

Quantitative data were analyzed using binary logistic regression to explore which socio-demographic factors predicted frequent takeaway consumption. Variables for the regression model were selected through univariate analyses, and categorical variables were collapsed when needed for statistical validity.

Key findings

Out of 246 participants, 189 were eligible for analysis. Most were female (95%), White (86%), well-educated (78%), and lived with a partner and children (83%) in high-income households (77%). About one-third lived in more deprived areas, though the sample underrepresented ethnic minorities (14% vs 18% national average) and overrepresented degree holders (78% vs 34% nationally).

Takeaway food was consumed infrequently (less than once a week) by 74% and frequently (once a week or more) by 26%. Most frequent consumers had takeaway once a week (84%), while a few had it several times per week (16%).

Over the years, 44% reported no change in consumption frequency, 31% reported a decrease, and 25% reported an increase. Decreases were mainly due to cost or income constraints; increases were often linked to children growing old enough to eat takeaway food.

Regression analysis revealed that middle-income households were significantly less likely to frequently consume takeaway food compared to low-income households. Participants from moderately deprived areas were also less likely to consume frequently than those in the most deprived areas. Notably, high-income households showed no significant difference in frequency compared to low-income households.

Takeaway food was most commonly consumed during Friday or Saturday dinners (75%). Families usually ate together at the table, made joint decisions about orders, and mostly ordered through food apps, especially pizza.

Convenience, ease, enjoyment, and treating the family were key motivations. Downsides included high cost, unhealthiness, occasional guilt, and dissatisfaction with quality or service.

Conclusions

The researchers found that while takeaway consumption was common, it was usually infrequent, framed as a convenient and enjoyable family treat. Socio-demographic analysis revealed a non-linear relationship where both low- and high-income families consumed takeaway more frequently than middle-income families, indicating complex socio-economic dynamics.

The study’s mixed-methods design and efforts to recruit a diverse sample strengthened its findings. However, the overrepresentation of highly educated, White mothers may have led to underestimates of takeaway frequency. The study did not assess the nutritional quality of takeaways, and the perspectives of males were limited.

Policymakers should consider the emotional and social value of takeaway meals to families and prioritize improving their nutritional quality over restricting access, including interventions addressing portion sizes, advertising standards, and reformulation. Future research should explore broader eating patterns and socioeconomic status-linked motivations, particularly how families balance convenience and enjoyment with nutritional concerns.