A new global metric shows how everyday foods, from beef to coffee, carry vastly different extinction costs, exposing how our diets and imports quietly shape the future of Earth’s wildlife.

Study: Food impacts on species extinction risks can vary by three orders of magnitude. Image Credit: Leszek Kobusinski / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Food, researchers leveraged global food production and consumption data (140 unique items) and a novel, high-resolution "LIFE" biodiversity metric to investigate the relative impacts of different foods on species extinction risk, using a metric they term "extinction opportunity costs."

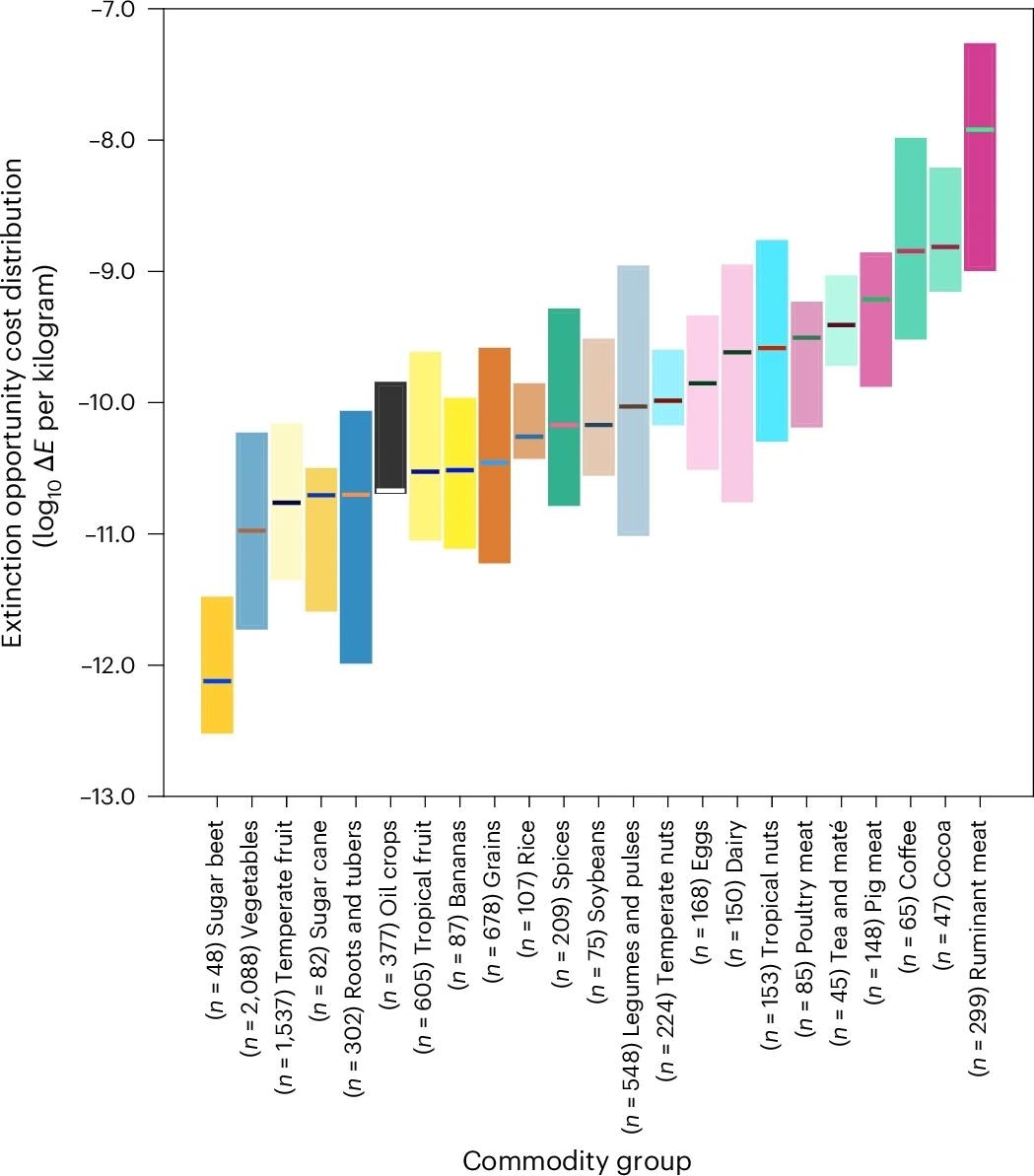

Study findings revealed that the impact of producing 1 kg of food can vary by up to three orders of magnitude across different food types. Animal products, especially ruminant meat, and commodities grown in the tropics (e.g., coffee and cocoa), were consistently observed to carry the highest species extinction risk. These findings elucidate the substantial relative costs of agricultural choices on ecology, thereby guiding future conservation and food production policy for sustainable outcomes.

Background

The global food production system is increasingly recognized as a primary threat to nature, linked to substantial land-use change and habitat destruction for agriculture. As the world's human population continues to rise, agricultural and food production is now recognized as the leading cause of the ongoing ecological extinction crisis.

Mitigating ongoing biodiversity loss associated with food production requires a robust understanding of which foods are most damaging and where they are produced, thereby informing conservation policy efforts. Unfortunately, previous attempts to quantify the biodiversity impacts of food have been limited.

Standard methods like life-cycle analysis (LCA) often rely on subjective metrics, are limited in their spatial and taxonomic scope, and lack the spatial detail to account for the fact that crops grown in a tropical biodiversity hotspot have a vastly different impact than the same crops grown in a temperate region. A more sophisticated, globally consistent approach is required to inform effective interventions, from individual dietary choices to international trade policy.

About the study

The present study addresses these knowledge gaps by developing a powerful new biodiversity metric called LIFE (Land-cover change Impacts on Future Extinctions), which leverages detailed global data on food production, consumption, and trade from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

LIFE is a high-resolution global map (1.8 km² resolution) that estimates the marginal impact of agricultural land use on the extinction risk of approximately 30,000 terrestrial vertebrate species, calculating the "extinction opportunity cost." This cost represents the forgone opportunity to restore biodiversity that arises from continued agricultural land use. In essence, it measures the potential reduction in extinction risk if a parcel of farmland were returned to its natural habitat.

The study used the LIFE metric to evaluate the impacts of 140 individual food products across both the holistic global context and within six exemplar countries with diverse dietary and trade profiles: the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), Japan, Brazil, India, and Uganda.

Global variation across and within commodities in the expected extinction impact of producing 1 kg of agricultural commodity or commodity group. The lower and upper boundaries of the boxes represent the production-mass-weighted 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively. Horizontal lines represent the weighted global median (50th percentile). Where commodities are grouped, the per-kilogram extinction risk values of each constituent commodity are weighted by their contribution (by mass) to the total global production of that group.

Study findings

Study findings revealed an unexpectedly high variation in the biodiversity impacts of different foods, spanning up to three orders of magnitude between foods with the lowest impacts versus those with the highest. Animal products were found to have a substantially greater effect on species extinction risk than staple plant-based foods.

Specifically, the global median opportunity cost of ruminant meat (e.g., beef and lamb) was found to be approximately 340 times greater than that of grains by mass. When rerunning the analysis to account for protein content, the impact of ruminant meat remained 100 times higher than that of protein-rich plants like soybeans and other legumes, highlighting the robustness of the analysis and the warning of the observed outcomes.

"Luxury" crops grown in tropical regions (coffee, cocoa, and tea) also ranked among the most impactful commodities per kilogram. Crucially, the impact also varied dramatically by provenance for the same product; for example, coffee from South America and sub-Saharan Africa had an impact approximately ten times greater than that produced in Southeast Asia.

Study analysis finally revealed that the biodiversity footprints of some nations are overwhelmingly externalized. A staggering 95% of the UK's and 98% of Japan's food-related extinction impacts occur in the countries from which they import.

In contrast, the effects from food consumed in Brazil and India were almost entirely domestic, at 98% and 96%, respectively. In the United States, the impact was also largely domestic, with imports accounting for only about 10%.

Across all countries studied, ruminant meat was the dominant driver of per capita impacts. Even in India, where a third of the population is lacto-vegetarian, ruminant meats (mainly sheep and goat) were found to contribute to 40% of the country's total impact on species extinction due to food production.

Conclusions

The present study provides the most detailed and globally comprehensive assessment to date of how different foods contribute to the extinction crisis. Animal products, particularly ruminant meat, and foods grown in tropical biodiversity hotspots were revealed to carry an excessively disproportionate environmental burden. Study analysis underscores the immense potential for dietary change to mitigate harm.

Encouragingly, data from the US-based scenario shows that shifting from a typical Western diet to the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet, with a reduction in ruminant meat consumption from 4% to 1%, reduces the extinction opportunity cost of an individual's diet by almost three-quarters. The study also found that shifting to hypothetical vegetarian and vegan diets in the US resulted in even greater reductions, cutting the remaining impact by more than half again, while a similar shift to a plant-based diet in the UK was found to reduce the effects by just over 50%.

However, the authors are careful to note several important caveats and limitations to their work. First, the analysis does not include all commodities, notably omitting aquatic foods, palm oil, and sugar due to data challenges.

Second, the study relies on relatively coarse data and does not yet account for the intensity of agricultural production, such as intensive versus extensive grazing, or impacts on plants and invertebrates.

Third, the authors stress that their metric is "marginal," meaning it is designed to compare the effect of one additional unit of a food and cannot be simply scaled up to calculate the total global impact of agriculture.

Finally, the study focuses exclusively on extinction risk from land use, and does not measure other critical harms like those from fertilizer runoff, pesticide use, or greenhouse gas emissions.

The authors also caution against simplistic policy interpretations. For example, while the UK and Japan "offshore" their biodiversity impact, the paper warns that policies promoting low-yielding domestic agriculture could inadvertently increase reliance on imports from more biodiverse regions, potentially causing a net increase in global biodiversity loss. These findings suggest that while the present scenario appears bleak, informed dietary changes and carefully considered policies may substantially improve future outcomes.

Journal reference:

- Ball, T. S., Dales, M., Eyres, A., Green, J. M. H., Madhavapeddy, A., Williams, D. R., and Balmford, A. (2025). Food impacts on species extinction risks can vary by three orders of magnitude. Nature Food, 6(9), 848–856. DOI: 10.1038/s43016-025-01224-w. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-025-01224-w