Introduction

What is ovarian aging?

Biological age and epigenetic clocks

Biomarkers in ovarian aging

Epigenetic clocks applied to reproductive tissue

Predictive use of ovarian aging clocks

Challenges, limitations, and future directions

References

Further reading

Epigenetic clocks provide a molecular framework for assessing biological ovarian age by integrating DNA methylation patterns with hallmarks of reproductive aging. While these clocks show moderate predictive value for fertility outcomes such as IVF success, they currently function best as complementary research tools rather than standalone clinical diagnostics.

Image Credit: 80's Child / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: 80's Child / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Chronological age has historically been considered the primary determinant of female fertility. Compared with the biological ovarian age, which can be estimated using epigenetic clocks, the biological ovarian age measures the cumulative impact of oxidative stress and environmental exposure on the ovary and, in turn, on fertility. Biological ovarian aging integrates molecular hallmarks, including mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere attrition, genomic instability, altered DNA repair capacity, chronic inflammation, and epigenetic drift, all of which may precede clinical markers of diminished ovarian reserve.1,2,5

This article discusses evidence from DNA methylation studies, selected transcriptomic investigations relevant to cellular stress responses, and the predictive power of epigenetic age acceleration to elucidate the benefits and limitations of this novel fertility assessment approach.

What is ovarian aging?

Ovarian aging is defined as the gradual and irreversible decline in both the quantity and quality of the ovarian follicle pool, a process that determines the female reproductive lifespan. Decades of research have established that, unlike somatic organs that may maintain function into late adulthood, the ovary follows an accelerated trajectory of senescence that culminates in menopause.1

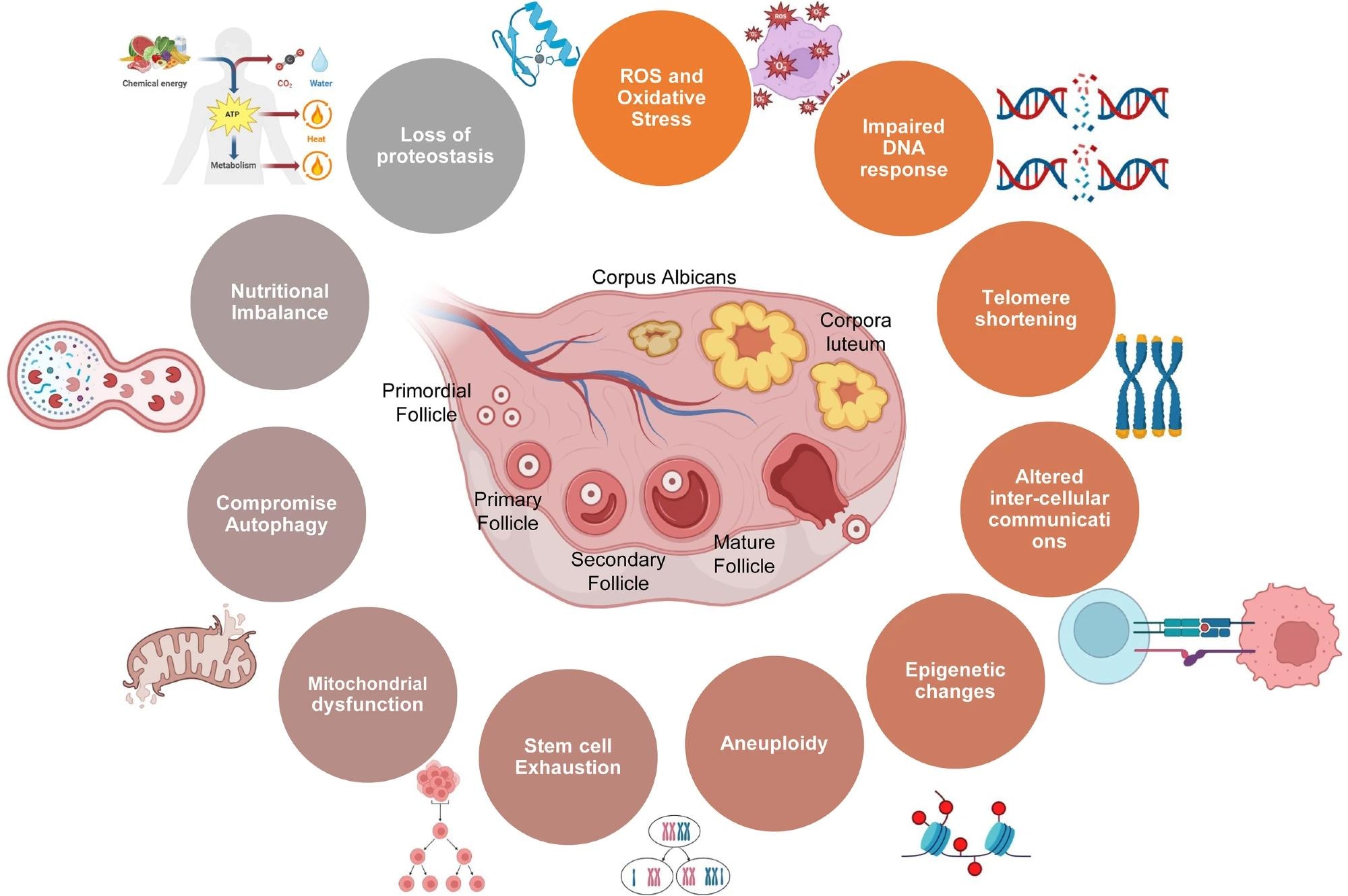

This decline in reproductive capacity leads to fewer available oocytes that are more likely to have chromosomal abnormalities, which leads to higher rates of miscarriage and implantation failure in older women.1 Growing evidence indicates that biological ovarian age reflects the physiological state of the female reproductive tissue that is influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and environmental exposures.2 Age-associated aneuploidy, impaired DNA damage response pathways (including BRCA1/2-related mechanisms), shortened telomeres, and stem cell depletion further contribute to declining oocyte competence and ovarian reserve.5

Ovarian aging is driven by oxidative stress, in which an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses damages cells. Specifically, excess ROS production induces apoptosis in granulosa cells and disrupts mitochondrial function essential for oocyte competence.1 Oxidative stress also activates inflammatory pathways such as NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and accelerates telomere shortening, thereby compounding follicular loss.1,5

Schematic showing various factors involved in ovarian aging.5

Biological age and epigenetic clocks

One of the most accurate measurements of biological age is the epigenetic clock, a metric that leverages DNA methylation, which refers to the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases in DNA, to estimate biological age.4 DNA methylation patterns are dynamic and change predictably over time, thereby serving as a robust molecular record of aging.4 First-generation clocks were designed to predict chronological age, whereas second-generation clocks (e.g., PhenoAge and GrimAge) incorporate morbidity and mortality-related markers to better capture biological aging processes.7

When an individual's predicted epigenetic age exceeds their chronological age, they exhibit epigenetic age acceleration (EAA).4,5 EAA reflects the cumulative burden of stress, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction.

Mitochondria are involved in EAA by providing essential co-substrates, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA), required for epigenetic modifications, indicating that mitochondrial dysfunction directly accelerates epigenetic aging.5 Mitochondria also supply α-ketoglutarate and ATP, which regulate histone and DNA demethylation reactions, establishing bidirectional nuclear–mitochondrial epigenetic cross-talk that influences ovarian longevity.5

Biomarkers in ovarian aging

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is considered a robust biomarker for cellular aging because it regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Within the ovary, specific methylation changes regulate folliculogenesis, the maturation of immature ovarian follicles, and steroidogenesis, which involves the enzymatic conversion of cholesterol to active steroid hormones.2,4

Age-related changes in DNA methylation are associated with poorer reproductive outcomes. These methylation patterns change markedly with reproductive aging and may diverge from chronological age, revealing a ‘younger’ or ‘older’ ovarian phenotype that correlates with fertility potential.4 Epigenome-wide association studies have identified CpG sites linked to ovarian reserve markers such as anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and antral follicle count (AFC), suggesting systemic methylation signatures may partially reflect ovarian functional decline.4,7

Molecular Technologies to Improve Oocyte Quality and Ovarian Aging

Epigenetic clocks applied to reproductive tissue

The incorporation of epigenetic clocks into reproductive tissues such as granulosa cells, cumulus cells, and leukocytes has provided crucial insights that have been used to more accurately guide fertility treatments.2 For example, women who achieve successful live births (LB) following in vitro fertilization (IVF) often possess a younger epigenetic age profile as compared to those who do not.6

In a prospective cohort of 379 women undergoing IVF, blood-based epigenetic age calculated using a simplified CpG model was significantly lower in women who achieved live birth, and each additional year of epigenetic age was associated with reduced odds of success even after adjustment for AFC.6

Although epigenetic clocks may modestly improve prediction when combined with established ovarian reserve markers, chronological age and ovarian reserve parameters remain central determinants of outcome. Tissue specificity can further enhance their predictive accuracy. Clocks trained specifically on granulosa cells, which surround the egg, provide distinct insights into the ovarian microenvironment that are not detected in other tissue analyses.2 However, granulosa- and endometrium-derived clocks remain largely investigational and have not yet been clinically validated for routine fertility decision-making.2,7

Predictive use of ovarian aging clocks

The predictive utility of ovarian aging clocks is attributed to their ability to predict outcomes when traditional markers fail. For example, in a prospective study of 379 women undergoing IVF, epigenetic age was a significant predictor of live birth success.6

Image Credit: Marko Aleksandr / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Marko Aleksandr / Shutterstock.com

Predictive use of ovarian aging clocks

Specifically, for every one-year increase in DNA methylation age, the likelihood of a live birth decreased by approximately 9%, even after adjusting for ovarian reserve. However, the predictive accuracy was moderate (area under the curve ~0.65–0.69 when combined with AFC or AMH), indicating that epigenetic age should currently be interpreted as a complementary rather than a standalone biomarker. Thus, epigenetic age acceleration or deceleration may provide incremental prognostic information, particularly in certain age subgroups such as women aged 31–35 years, but does not replace established clinical predictors.6

Challenges, limitations, and future directions

Despite significant advantages over conventional chronological clock-based approaches, epigenetic clocks are not widely used in clinical practice. Current epigenetic clocks often fail to meet the rigorous standards required for individual-level diagnostics due to measurement noise and technical variation across platforms. Single-time-point estimates may fall within assay variability, and differences in preprocessing pipelines, array platforms, and cell composition can substantially influence clock outputs.8

A secondary challenge to their adoption is the lack of tissue specificity, as an epigenetic clock that is accurate for blood may not accurately reflect the biological age of the ovary.2 Researchers have also raised ethical concerns about the potential misuse or overinterpretation of biological age scores in direct-to-consumer testing, particularly in the absence of established diagnostic cut-off values.8 Furthermore, transient physiological stressors, illness, or inflammatory states may alter methylation profiles independent of long-term ovarian aging, complicating clinical interpretation.8

These limitations underscore the need for additional research to refine ovarian tissue clocks through comprehensive validation in larger, more diverse cohorts. Future development will likely require fertility-specific models that undergo rigorous prospective validation before clinical implementation, rather than direct translation of population-trained epigenetic clocks into reproductive medicine.2,7,8

References

- Yan, F., Zhao, Q., Li, Y., et al. (2022). The role of oxidative stress in ovarian aging: a review. Journal of Ovarian Research 15(1). DOI: 10.1186/s13048-022-01032-x. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13048-022-01032-x

- Lin, J., Chen, Y., Wang, S., et al. (2025). Epigenetic clocks of female reproductive system aging: Current application and future prospects. World Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 14(2). DOI: 10.5317/wjog.v14.i2.108149. https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6220/full/v14/i2/108149

- Bouchama, A., Aziz, M. A., Al Mahri, S., et al. (2017). A Model of Exposure to Extreme Environmental Heat Uncovers the Human Transcriptome to Heat Stress. Scientific Reports 7(1). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-09819-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-09819-5

- Knight, A. K., Spencer, J. B., & Smith, A. K. (2023). DNA Methylation as a Window into Female Reproductive Aging. Epigenomics 16(3); 175-188. DOI: 10.2217/epi-2023-0298. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/epi-2023-0298

- Mani, S., Srivastava, V., Shandilya, C., et al. (2024). Mitochondria: the epigenetic regulators of ovarian aging and longevity. Frontiers in Endocrinology 15. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1424826. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2024.1424826/full

- Marinello, D., Reschini, M., Di Stefano, G., et al. (2025). Epigenetic age and fertility timeline: testing an epigenetic clock to forecast in vitro fertilization success rate. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 23(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12958-025-01429-5. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12958-025-01429-5

- Li Piani, L., Vigano’, P., & Somigliana, E. (2023). Epigenetic clocks and female fertility timeline: A new approach to an old issue? Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 11. DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1121231. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2023.1121231/full

- Apsley, A. T., Etzel, L., Ye, Q., & Shalev, I. (2025). From population science to the clinic? Limits of epigenetic clocks as personal biomarkers. Epigenomics 17(18); 1447-1461. DOI: 10.1080/17501911.2025.2603880. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12714307/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 17, 2026