Introduction

The gut microbiome: a dynamic ecosystem

Microbial dysbiosis and CRC

Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori

Microbial metabolites and host signaling

Host immune response and tumor microenvironment

Clinical implications and future directions

References

Further reading

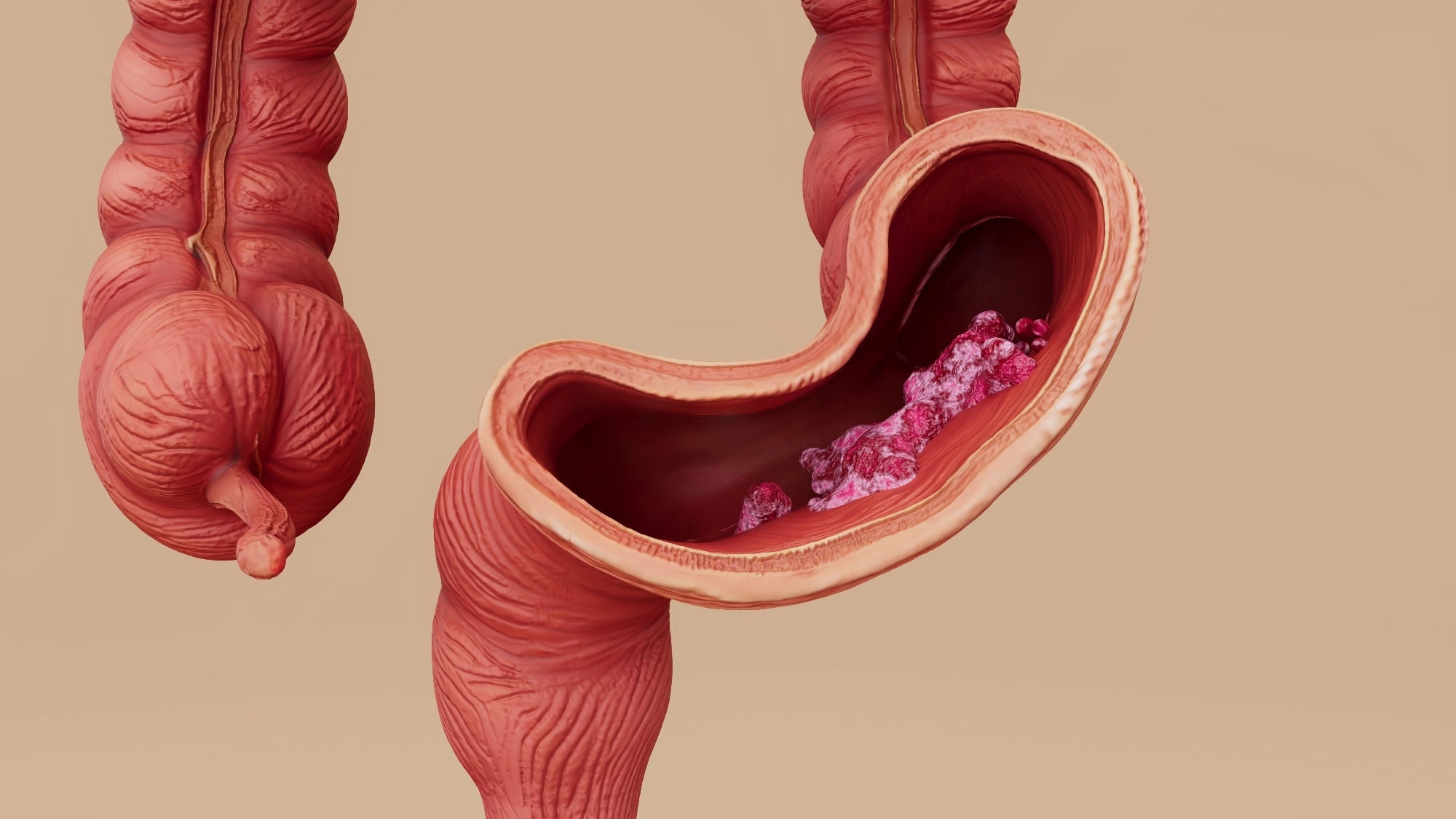

This article explains how host–microbiome interactions contribute to gastrointestinal cancer risk through microbial genotoxins, metabolic signaling pathways, immune dysregulation, and tumor microenvironment remodeling in colorectal and gastric cancers. It synthesizes current evidence to show how dysbiosis, microbial metabolites, and pathogen-driven signaling alter epithelial integrity, inflammation, and therapeutic response.

Image Credit: Julien Tromeur / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Julien Tromeur / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Rising rates of colorectal, pancreatic, esophageal, and other less common gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are increasingly being reported among patients 50 years and younger, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities. Emerging evidence indicates that host–microbiota metabolic crosstalk, immune modulation, and microbial genotoxins play central mechanistic roles in tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic response across GI malignancies. Importantly, many microbiome–cancer associations are derived from observational and preclinical studies, and causal relationships in humans remain an area of active investigation.1-3

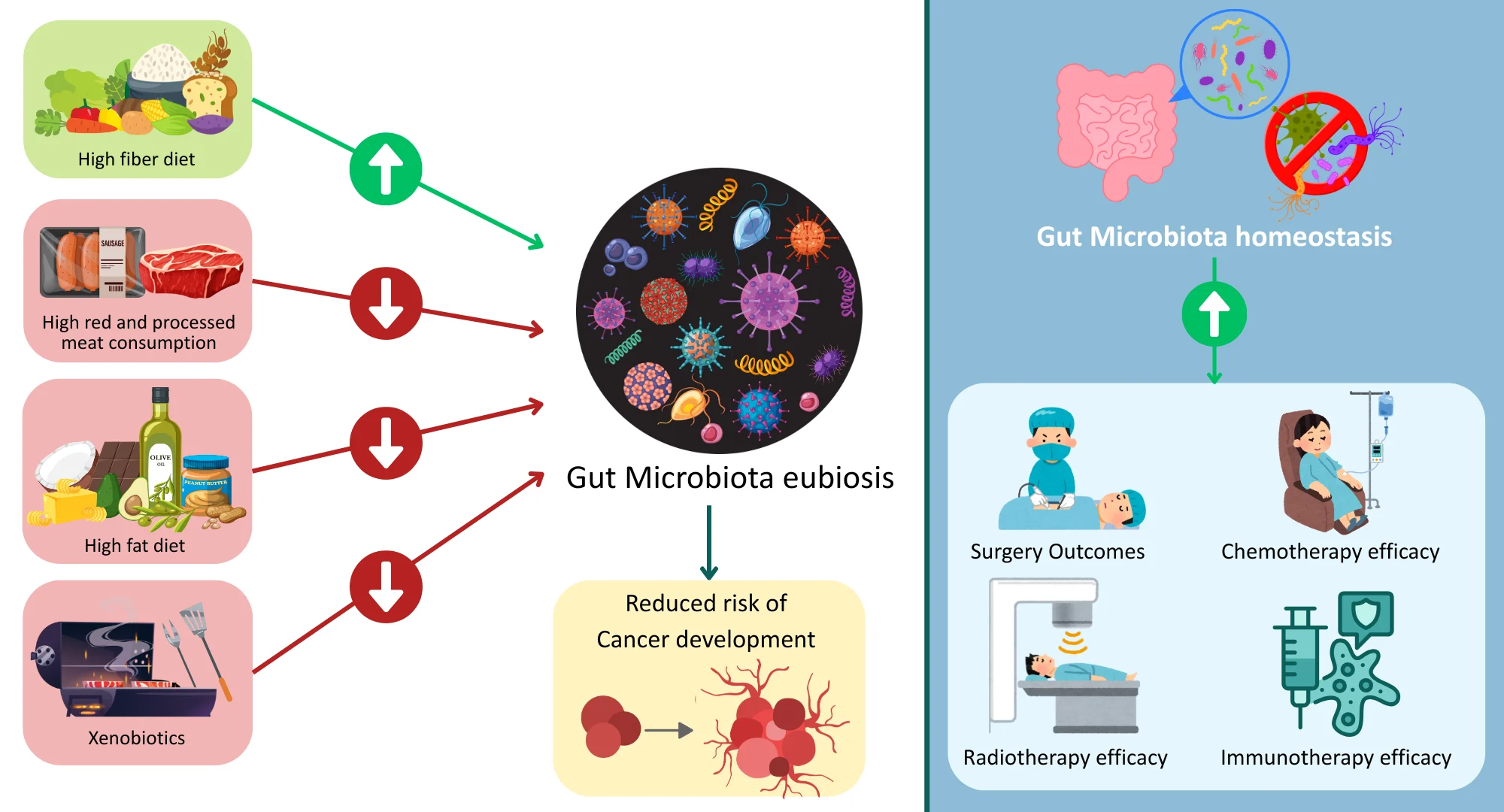

The interplay between the gut microbiota and colorectal cancer1

The gut microbiome: a dynamic ecosystem

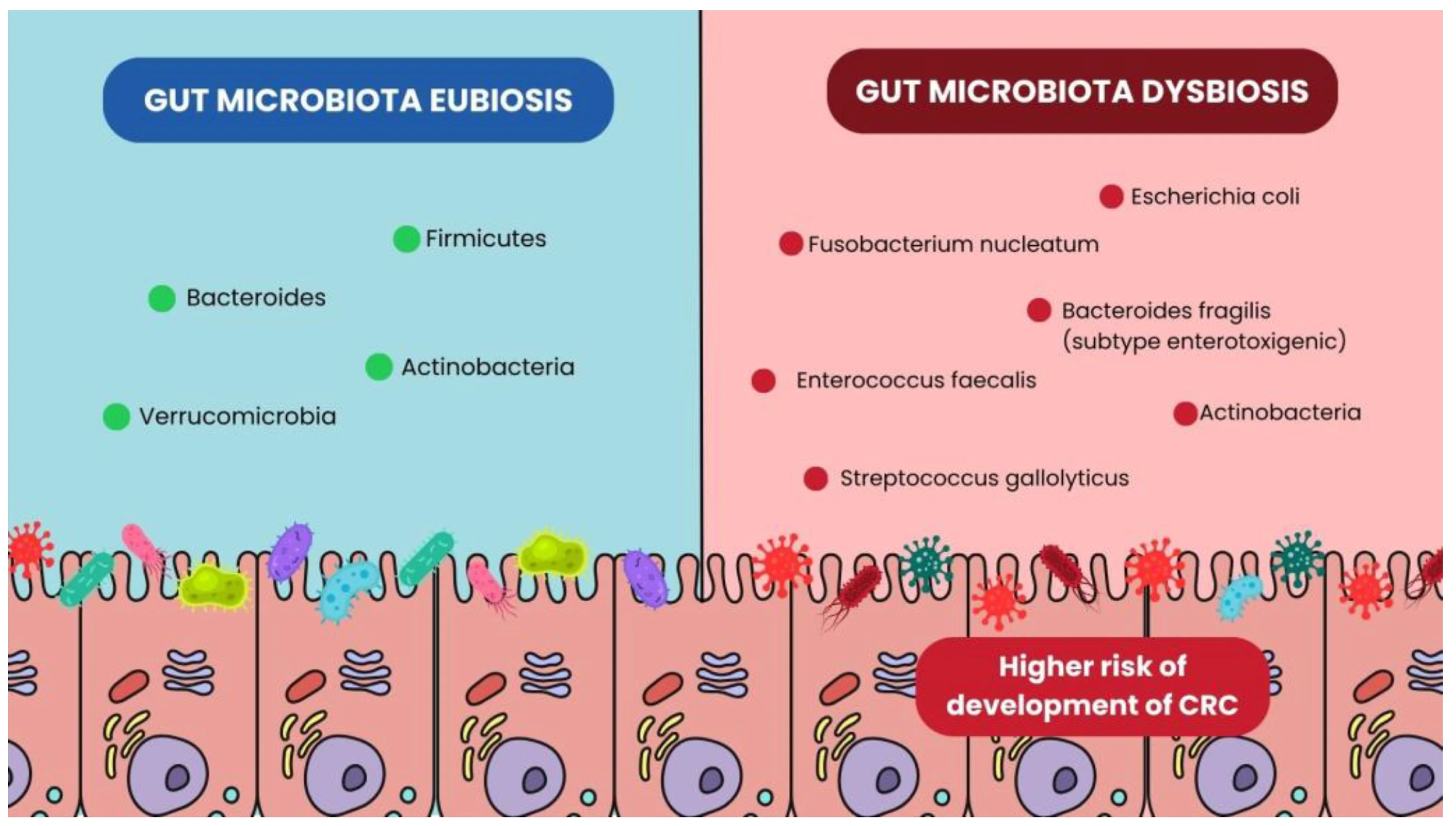

In gut dysbiosis, characterized by reduced microbial diversity in the GI tract, an enrichment of pathogenic taxa leads to chronic low-grade inflammation. Dysbiosis typically involves depletion of beneficial butyrate-producing taxa (e.g., Roseburia, Lachnospiraceae) and enrichment of pro-inflammatory pathobionts such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF), and pks-positive Escherichia coli.1-3 However, microbial composition varies across individuals, tumor subtypes, and anatomic regions of the GI tract, contributing to heterogeneous findings across studies.1,2 This inflammatory environment induces continuous activation of pro-inflammatory pathways like nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) that disrupt epithelial integrity and increase cell proliferation.1,3

Disruption of the intestinal barrier also occurs as a result of altered microbial communities that impair tight junctions and mucosal immunity. This leaky gut state allows bacteria and their products, including lipopolysaccharides, to translocate into host tissues, further amplifying immune activation and sustaining a tumor-promoting microenvironment.1,3 Certain strains of Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis also produce toxins and metabolites that induce DNA damage through oxidative stress, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species production, and double-strand breaks.1,3 For example, pks+ E. coli produces colibactin, a genotoxin that alkylates DNA and induces double-strand breaks, while ETBF secretes fragilysin, a metalloprotease that cleaves E-cadherin and activates β-catenin signaling.1,2

Bacterial differences in Gut Microbiota eubiosis and dysbiosis conditions.1

Microbial dysbiosis and CRC

Microbial dysbiosis increases the risk of colorectal cancer by facilitating prolonged immune activation that contributes to continuous epithelial injury, thereby supporting tumor initiation and progression.1,3 Dysbiosis also compromises intestinal barrier integrity, which allows bacteria and toxins to enter the body, causing inflammation and tissue damage to further increase cancer risk.1,3

Dysbiosis-associated microorganisms, such as specific strains of Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis, release toxins and metabolites, including colibactin, secondary bile acids, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), that directly induce DNA damage, genomic instability, and epigenetic alterations. Fusobacterium nucleatum further promotes tumorigenesis through its FadA adhesin, which binds E-cadherin and activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling, increasing expression of oncogenes such as c-Myc and Cyclin D1.1 High intratumoral abundance of F. nucleatum has also been associated with specific molecular subtypes of CRC, including CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) positivity and microsatellite instability (MSI).1 The combination of these genotoxic effects, along with chronic inflammation and intestinal barrier disruption, converges to drive the development of colorectal cancer.1,3

Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the most established example of a bacterium that directly contributes to gastric cancer risk and, as a result, is classified as a Group I carcinogen. Long-term colonization of the gastric mucosa by H. pylori leads to chronic active gastritis, during which immune cells continue to infiltrate and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, ROS, and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). This chronic inflammatory state leads to oxidative DNA damage and compromised epithelial repair mechanisms, both of which are ideal conditions for neoplastic transformation.2,3

Chronic inflammation induced by H. pylori ultimately results in progressive mucosal damage, leading to atrophic gastritis and loss of the acid-secreting parietal cells, with subsequent formation of intestinal metaplasia. These precancerous changes, which are often described in the Correa cascade, increase susceptibility to gastric adenocarcinoma. Reduced gastric acidity further alters the gastric microbiome, allowing colonization by non-H. pylori bacteria that may generate carcinogenic metabolites such as N-nitroso compounds to further amplify cancer risk.2,3 This progression has been described as an “H. pylori initiation–non-H. pylori acceleration” cascade, in which secondary microbial colonizers contribute to tumor promotion.2

In parallel, H. pylori actively manipulates host immune responses. Specifically, virulence factors such as cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) and vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) dysregulate key signaling pathways, including NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, to promote immune evasion, epithelial proliferation, and tumorigenesis.2,3 CagA-positive strains additionally activate Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT3, ERK/MAPK, and Hedgehog signaling pathways, while promoting PD-L1 expression to facilitate immune escape. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated gastric cancer represents another microbiologically influenced subtype characterized by distinct immune and epigenetic features. Emerging evidence also suggests that fungal dysbiosis, including enrichment of Ascomycota species, may accompany gastric carcinogenesis.2

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate are produced by bacterial fermentation of fiber. During homeostasis, SCFAs promote epithelial energy metabolism, barrier reinforcement, and regulatory T-cell (Treg) function while suppressing pro-inflammatory signals. Butyrate, in particular, exerts anti-tumor effects by promoting apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in transformed epithelial cells while limiting excessive proliferation.1,3 SCFAs also signal through G-protein-coupled receptors (e.g., GPR41, GPR43) and act as histone deacetylase inhibitors to regulate immune and tumor suppressor gene expression.3 Additionally, microbial metabolism of tryptophan generates indole derivatives that activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), influencing immune cell differentiation and mucosal homeostasis.3

Comparatively, gut dysbiosis interferes with bile acid metabolism, thereby increasing the formation of secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid, which damage DNA and the intestinal epithelium and activate oncogenic pathways involving NF-κB and Wingless-related integration site (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling. Secondary bile acids can also impair apoptosis and promote chronic inflammation, fostering a tumor-permissive microenvironment.1,3

Host immune response and tumor microenvironment

The gut microbiome is a key architect of the host immune response and tumor microenvironment in gastrointestinal cancers. Microbes and their products, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns and metabolites, engage host pattern-recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors, leading to activation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB. NF-κB induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) to perpetuate a cancerous environment.2,3

Microbial signals influence adaptive immunity by altering T-cell differentiation, effector function, and exhaustion, as well as modulating immune checkpoints such as programmed death ligand 1 (PDL-1) expression on epithelial and immune cells.2,3 Gut microbes also shape macrophage polarization toward pro-tumorigenic M2-like tumor-associated macrophages and promote expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, thereby suppressing cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell activity.2 Dysbiosis may also impair dendritic cell maturation, alter natural killer (NK) cell function, and influence the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures within tumors, collectively reshaping anti-tumor immunity.2

Clinical implications and future directions

Recent advancements in metagenomics and metabolomics enable the precise identification of cancer-associated bacteria and altered metabolic pathways. These non-invasive tools enable the detection of genotoxin-producing bacteria and unique metabolic signatures, allowing researchers to understand tumor development and offering new possibilities for early diagnosis and personalized treatment.1,3 Microbiome composition has also been linked to chemotherapy efficacy, immunotherapy responsiveness, and treatment-related toxicity in GI cancers.1,2

Therapeutically, multiple microbiome-targeted approaches are under investigation. For example, researchers are increasingly studying the role of probiotics, prebiotics, dietary fiber enrichment, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in restoring microbial equilibrium and improving therapeutic outcomes.1,2

Though promising, complex host-microbe interactions and high variability in people limit general applications. Large, longitudinal human cohort studies, integration of multi-omics platforms, and standardized analytical methods are needed to translate this research into real-world treatments.1,3

References

-

- Cintoni, M., Palombaro, M., Zoli, E., et al. (2025). The Interplay Between the Gut Microbiota and Colorectal Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Microorganisms 13(6). DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms13061410. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/13/6/1410

- Elghannam, M. T., Hassanien, M. H., Ameen, Y. A., et al. (2025). Gut microbiome and gastric cancer: microbial interactions and therapeutic potential. Gut Pathogens 17. DOI: 10.1186/s13099-025-00729-w. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13099-025-00729-w

- Yu, J., Li, L., Tao, X., et al. (2024). Metabolic interactions of host-gut microbiota: new possibilities for the precise diagnosis and therapeutic discovery of gastrointestinal cancer in the future - a review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 203. DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104480. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040842824002233

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 19, 2026