Introduction

Key spectroscopic techniques

How spectroscopy enables bio-monitoring?

Major application areas

Limitations and challenges

Future Outlook

References

Further Reading

This article explains how spectroscopic techniques enable non-invasive, real-time bio-monitoring of biological, environmental, and biotechnological systems. It highlights core methods, application areas, limitations, and emerging advances that support faster decision-making and process control.

Image credit: S. Singha/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: S. Singha/Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Bio-monitoring refers to tracking changes in biological molecules or reactions over time. When using miniaturized flow systems, the ability to monitor concentrations within microchannels is essential for studying both physical and chemical behavior during processes. Non-invasive, accurate measurements are very important, as they can help facilitate faster healthcare decisions, industrial process control in biotechnology, and enable the monitoring of the environment. Diagnosing biomolecules for disease analysis and ecology monitoring is one of the most proven examples.

In simple terms, spectroscopy analyzes a sample by measuring how it interacts with light. It can also detect and quantify molecules, while being non-destructive with minimal treatment or no sample preparation. These properties make spectroscopy particularly suitable for in-line and on-line bio-monitoring in continuously operated microreactor and bioprocess systems, where rapid feedback is required without disrupting the system.1

This article highlights how spectroscopy enables fast, non-invasive bio-monitoring of biological systems in healthcare, environmental science, and biotechnology.

Key spectroscopic techniques

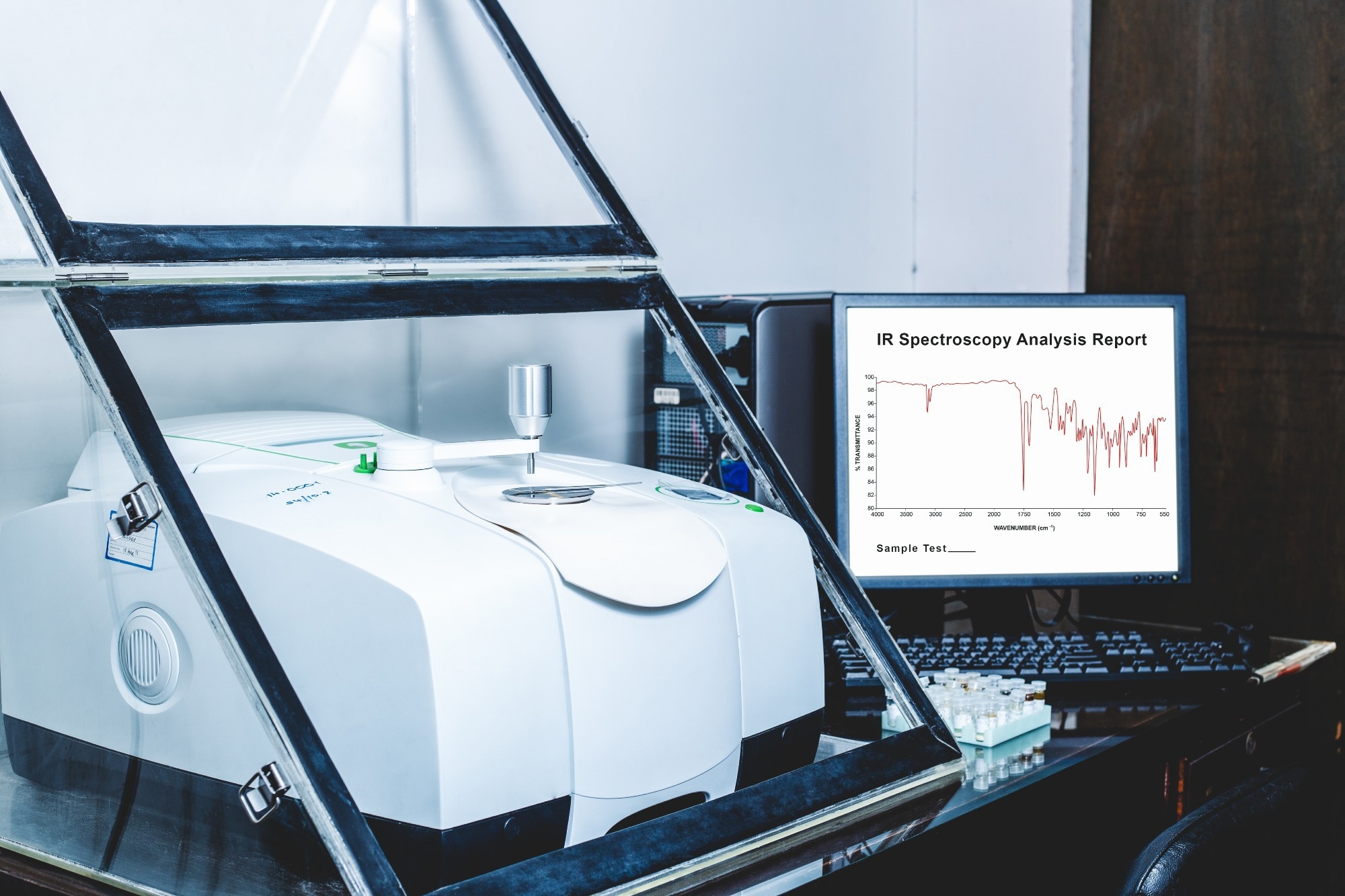

The primary spectroscopic techniques employed in bio-monitoring include ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), infrared (IR), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR), Raman, and fluorescence-based approaches. UV-Vis spectroscopy is commonly used to characterize and identify compounds, as well as monitor changes in concentration in liquids or solids. It also serves as a real-time and in-line analytical sensor for quality tracking and process control in the biological and pharmaceutical applications, with minimum sample preparation.1

IR methods support biomolecular fingerprinting, as in the mid-IR region, molecules create unique vibrational patterns. Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is also frequently applied for bio-monitoring due to its deeper penetration depth and suitability for aqueous systems, albeit with greater reliance on chemometric models because of overlapping bands. FTIR converts raw interferograms into spectra, mapping the absorption or transmission of IR light across frequencies to form reproducible molecular fingerprints. Label-free, non-destructive Raman spectroscopy is chosen widely in analysis as few or no sample preparation steps are required and it can investigate complex biological materials like biofluids, cells, and tissues.1

Finally, fluorescence spectroscopy is highlighted, along with UV-Vis, IR, and Raman, as a means of tracking processes and characterizing biomolecules and metabolic cofactors due to its exceptionally high sensitivity for intrinsically fluorescent compounds, making it particularly useful for real-time bioprocess monitoring.2

How spectroscopy enables bio-monitoring?

Bio-monitoring based on spectroscopy involves the detection of changes in light absorption, scattering, or emission resulting from the interaction of light with the molecules that make up a biological sample. In IR spectroscopy, biomolecules absorb IR energy at frequencies corresponding to specific molecular bonds as transitions between vibrational states, creating absorption bands that serve as unique chemical signatures. The magnitude of the absorbed light is then proportional to concentration across a known path length (Beer–Lambert behavior).2

In Raman spectroscopy, a laser beam shines on the sample, and most photons are elastically scattered, while a small fraction undergoes inelastic scattering (Stokes or anti-Stokes shifts). These frequency shifts represent molecular vibrational modes, and the Raman signal intensity scales with the number of molecules present, allowing concentration estimation. In fluorescence spectroscopy, molecules absorb light and reach an excited electronic state; upon relaxation, they emit lower-energy light. This emission provides highly sensitive signals for monitoring intracellular metabolites such as NADH, NADPH, and aromatic amino acids.2 As physiology or composition changes, spectral features shift in peak position and intensity, reflecting variations in molecular concentration or structure.

Unlike conventional biochemical tests that involve sampling with off-line analysis, spectroscopy enables fast, non-destructive, and potentially continuous monitoring without reagent addition or complex sample preparation, making it well-suited for real-time process analytical technology (PAT) applications.2

Major application areas

Spectroscopy-based bio-monitoring is widely used in healthcare, biomedical research, and environmental monitoring. Raman spectroscopy is used to measure the chemical composition of complex biological samples, including cells, tissues, and biofluids, thereby supporting rapid tissue analysis and disease diagnostics.1

Mass spectrometry, including electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, is used for analyzing peptides and proteins and is applied in clinical studies for therapeutic drug monitoring, diagnostics, and toxicological analysis. Although not an optical spectroscopic technique, it is often integrated with spectroscopic monitoring strategies in advanced bio-analytical workflows. In environmental monitoring, UV-Vis spectroscopy enables the online detection of photodegradation of dyes, such as methylene blue and methyl orange. At the same time, microfluidic platforms enable the on-site detection of heavy metals, such as mercury ions.1

Fluorescence spectroscopy is used to assess river water quality by characterizing the natural organic matter present. Methods that combine surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) with microfluidics enable the trace detection of toxic compounds, such as thiram, cadmium, and other low-level contaminants. In biotechnology and bioprocessing, real-time monitoring using non-invasive optical probes inside bioreactors enables online analysis of cell growth, metabolism, and product formation, facilitating automated feedback control strategies during fermentation processes.1

Limitations and challenges

Practical challenges in spectroscopic bio-monitoring primarily arise from the complexity and overlapping nature of biological signals. Spectra from real samples are often noisy and highly correlated, requiring baseline correction, normalization, and multivariate analysis rather than direct readout. Fluorescence signals may depend on pH, temperature, and ionic strength, and can be affected by autofluorescence, photobleaching, or probe fouling, necessitating frequent recalibration.2,3

Additional limitations include sensitivity–specificity trade-offs; for example, overlapping NIR absorption bands reduce selectivity, while fluorescence offers high sensitivity but limited molecular coverage. Model transferability and long-term robustness remain key obstacles, as calibration models often require large representative datasets and periodic retraining as instrumentation and operating conditions evolve.2,3

In applications such as volatile organic compound (VOC) sensing, challenges include cross-sensitivity in complex gas mixtures, environmental interference from humidity and temperature fluctuations, and long-term sensor stability issues, all of which complicate accurate data interpretation and continuous deployment.3

Future Outlook

The future of spectroscopy-based bio-monitoring lies in real-time, in situ, and portable implementations. Studies demonstrate the growing success of miniaturized and portable instruments for on-site quality control and distributed process monitoring. Advances in hyperspectral and imaging spectroscopy are expected to add spatial resolution to conventional spectral measurements, strengthening applications in NIR and Raman bio-monitoring.1

As datasets expand, the integration of chemometrics with artificial intelligence, machine learning, and cloud computing will improve preprocessing, calibration robustness, and model transferability across instruments and environments.1,3

References

- Jurina, T., Cvetnić, T. S., Šalić, A., Benković, M., Valinger, D., Kljusurić, J. G., Zelić, B., & Jurinjak Tušek, A. (2023). Application of Spectroscopy Techniques for Monitoring (Bio)Catalytic Processes in Continuously Operated Microreactor Systems. Catalysts. 13(4). DOI:10.3390/catal13040690, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4344/13/4/690

- Mishra, A., Aghaee, M., Tamer, I. M., & Budman, H. (2025). Spectroscopic Advances in Real Time Monitoring of Pharmaceutical Bioprocesses: A Review of Vibrational and Fluorescence Techniques. Spectroscopy Journal. 3(2). DOI:10.3390/spectroscj3020012, https://www.mdpi.com/2813-446X/3/2/12

- Wang, Y., Zhou, X., Mao, S., Chen, S., & Guo, Z. (2025). Challenges and Applications of Bio-Sniffers for Monitoring Volatile Organic Compounds in Medical Diagnostics. Chemosensors. 13(4). DOI:10.3390/chemosensors13040127, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9040/13/4/127

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 12, 2026