Jun 3 2005

A new University of Southern California computer system lets a user "drive" a piece of music, using a wheel and foot controls. The Expression Synthesis Project (ESP) interface, devised by a team led by Elaine Chew of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, could be in the hands of consumers within two years.

Chew presented ESP May 28 at the New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME) 2005 conference at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Chew, an assistant professor of industrial and systems engineering, is also pianist performing a schedule of concert appearances in addition to her work at the Viterbi School's Daniel J. Epstein Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering. She says ESP "allows everyone a chance to experience what it's like to perform. It lets them appreciate the decisions made by a musician in interpreting the music."

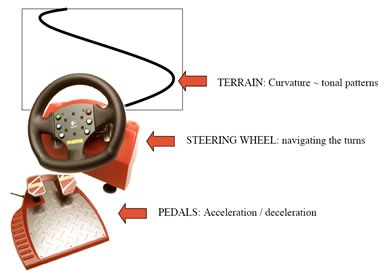

ESP "attempts to provide a driving interface for musical expression," according to Chew's published description. "The premise of ESP is that driving serves as an effective metaphor for expressive music performance. Not everyone can play an instrument but almost anyone can drive a car. By using a familiar interface, ESP aims to provide a compelling metaphor for expressive performance so as to make high-level expressive decisions accessible to non-experts."

Created by Chew, Alexandre R.J. François, a research professor in the Viterbi School, and graduate students Jie Liu and Aaron Yang, ESP starts with a piece of music the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) format, one that has been converted from the printed score. MIDI is the standard control language for driving musical synthesizers or other devices. François' Software Framework Architecture for Immersipresence and Modular Flow Scheduling Middleware, devised in 2001, is an important enabling element in the design of the system.

The score used as the test case in the development of ESP is the Hungarian Dance No. 5 in G-minor by Johannes Brahms. The piece was selected because it contains numerous moments of extreme speed ups and slow downs. To guide the musical performance, Chew and her colleagues used information from the score to create a "road" that corresponds to the structure of the piece. This is necessary, says Chew, because crucial cues from the score and its analysis, necessary for an informed performance, are not captured in the MIDI file.

The group is building tools to automate the process of creating such roads, applying artificial intelligence techniques to the analysis of the score. "Having the road build itself will be the most difficult part," says François.

The road's turns suggest to the driver when to slow down and speed up. however, the ultimate decision on what to do at each turn is entirely in the driver's hands (or foot). The foot pedals control both the tempo and the volume of the music. Additionally, buttons mounted on the wheel (see photo) act as the equivalent of the pedals on the piano, making the notes either sustain or cut off crisply.

Chew has carried on the ESP research at the Viterbi School's Integrated Media Systems Center, where she is Research Director for Human Performance Engineering. She is the winner of an Early Career Award from the National Science Foundation.

She hopes ESP will open new doors into music for non-musicians, a chance "to try making and evaluating musical decisions themselves, to see what it's like to perform."