For the first time, researchers have successfully removed HIV-1 DNA from the genomes of living animals, a critical step towards a potential cure for the disease.

The team initially used drugs to suppress viral replication in mice. They then used the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to eliminate viral DNA that had hidden itself in immune cells. Without removing these fragments, the virus would have maintained its ability to start replicating again and progress to become AIDS.

"Our study shows that treatment to suppress HIV replication and gene editing therapy, when given sequentially, can eliminate HIV from cells and organs of infected animals," says study author Kamel Khalili, Director of the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University.

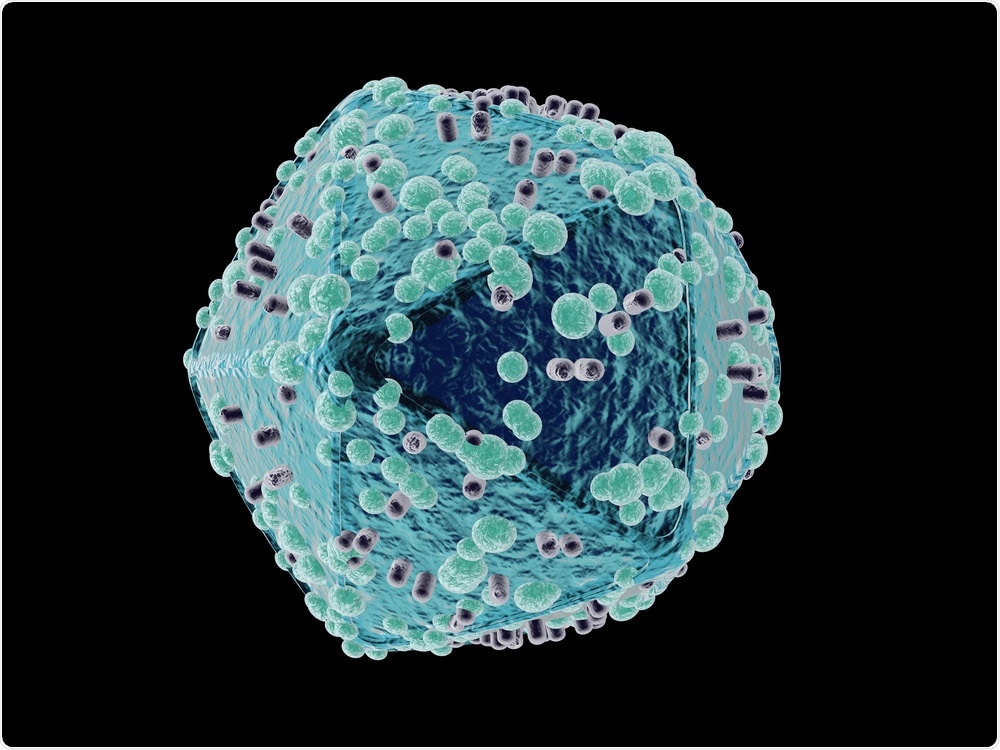

Spectral-Design | Shutterstock

Spectral-Design | Shutterstock

Currently, HIV is treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) which suppresses but does not destroy or eliminate the virus from the body. Used properly, ART can keep HIV at such low levels that it is not detectable in the blood, drastically lowering the risk of transmission through sexual contact or transfusion. The treatment is most effective when used to suppress viruses that actively replicate themselves and then infect healthy cells.

However, HIV has “learned” this over time and can eventually mutate to become resistant to the medications. Once ART is stopped, HIV rebounds and the virus copies itself again, fuelling the development of AIDS.

The virus can also “hide” itself in lymph and other tissue throughout the body where it lays dormant, only to start replicating with abandon once the immune system drops its guard. HIV rebound is directly attributed to the ability of the virus to incorporate its DNA into the genomes of immune cells, where it lies dormant and beyond the reach of ART.

All of this means that once a person has HIV, the virus can lay dormant in the body waiting to flood the immune system with millions of virions, years or even decades after the virus first infected a cell.

ART can therefore only help to an extent and is not a cure for HIV. It also requires life-long use.

Seeking out the virus and eliminating its every trace would, therefore, be a much more effective solution than ART, but scientists have not yet been able to develop a vaccine or any other therapy that achieves this.

‘HIV is a curable disease’

Now, researchers at Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University and the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) have reported a potential way to remove HIV from the genomes of infected animals using a combination of ART to suppress the virus and CRISPR-Cas9 to eliminate HIV genes from infected cells.

Tests showed that all traces of the virus had been completely eliminated in 30% of the animals.

This observation is the first step toward showing for the first time, to my knowledge, that HIV is a curable disease.”

Kamel Khalili

In previous experiments, the team had used CRISPR-Cas9 to develop a new gene therapy delivery system that removes HIV DNA from the genomes of rats and mice. They found that the tool effectively removed large fragments of the DNA from cells harboring the virus, significantly reducing expression of the viral DNA. However, the gene editing tool alone was not enough to completely eliminate the virus.

As reported in the journal Nature Communications, Khalili and team have now combined CRISPR-Cas9 with a new approach called long-acting slow-effective release (LASER) ART, which was co-developed by Howard E. Gendelman and Benson Edagwa, at UNMC.

LASER ART targets the harboring virions to suppress HIV replication for long periods of time so that ART is needed less frequently. This was made possible by changing the chemical structure of an antiretroviral drug. This altered drug was packaged into fat-soluble nanocrystals which can move through cell membranes in tissues where HIV is lying dormant such as the spleen, liver or lymph.

The nanocrystals are then stored within the cells of those tissues for weeks, where enzymes within the cells release the drug. The crystal structure allows the drug to be released more slowly, enabling it to continue destroying latent HIV as it starts to emerge and copy itself for months as opposed to days or weeks, as is the case with conventional ART.

‘A clear path to move ahead to trials’

"We wanted to see whether LASER ART could suppress HIV replication long enough for CRISPR-Cas9 to completely rid cells of viral DNA,” says Khalili.

To test the idea, the team used mice that had been engineered to produce human T cells that were susceptible to HIV infection and used LASER ART to suppress virus replication in the blood.

Next, they used CRISPR-cas9 to remove HIV from any cells infected with viral DNA – cells that would usually be missed by conventional ART. Khalili had previously managed to achieve this in a petri dish and in lab animals, but CRISPR alone was not enough because when the virus replicates it makes so many copies that the gene editing tool cannot keep up. In fact, when mice were treated with either LASER ART or CRISPR, HIV rebounded in just five to eight weeks.

However, once the two therapies were combined, they effectively eliminated HIV from about one-third of the animals.

Here, sequential long-acting slow-effective release antiviral therapy (LASER ART) and CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrate viral clearance in latent infectious reservoirs in HIV-1 infected humanized mice. These data provide proof-of-concept that permanent viral elimination is possible.

We now have a clear path to move ahead to trials in non-human primates.”

Kamel Khalili

If this works, it would pave the way for human testing. In 2015, Khalili co-founded a company called Excision Biotherapeutics, with plans to carry out human trials in the future, which he is optimistic about: “It seems that CRISPR might be the way to cure HIV—that’s what we’re hoping.”

Journal reference:

Dash, P. K. (2019). Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR Treatments Eliminate HIV-1 in a Subset of Infected Humanized Mice. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10366-y