The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has proved to be an elusive foe, evading immune surveillance while instigating hyperinflammatory responses that eventually destroy the host in a significant minority of cases.

Viral spikes are prime targets for neutralizing antibodies, and many have evolved immune evasion, some of which resemble aspects of the pH-dependent conformational masking. The Ebola virus masks its receptor binding site when the endosome is cleaved, while the HIV envelope protein also undergoes conformational masking, inducing non-neutralizing antibodies. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has a low folding enthalpy at the spike protein. This allows antibodies such as the molecule CR3022 to bind at high-affinity to it, but not to neutralize it.

The Spike (S) protein of the virus is an important target for neutralizing antibodies. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) on the S1 subunit of the S protein is a flap-like structure with a hinge, but the purpose of this movement has been a point of discussion.

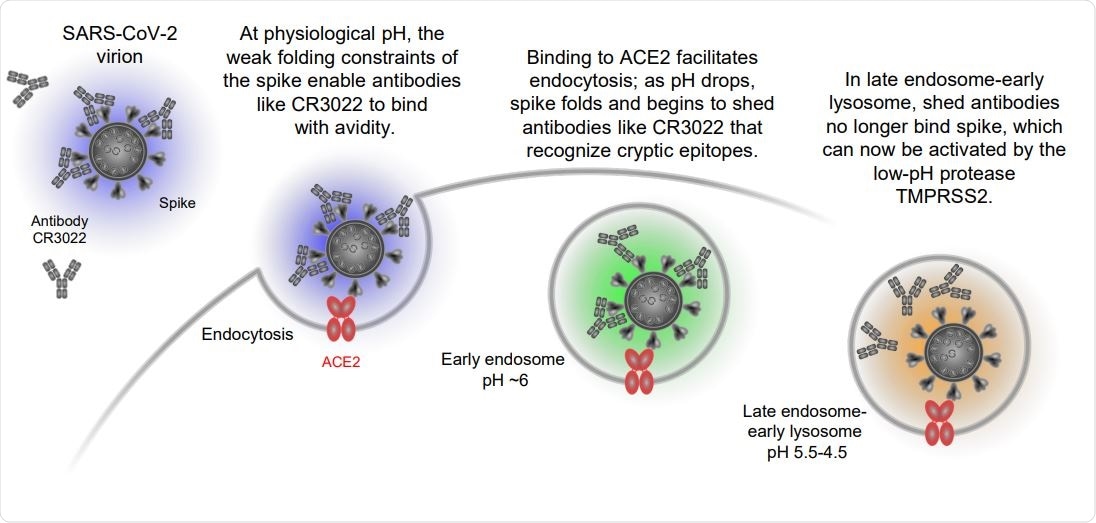

The S protein is a type I fusion machine. It interacts with the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 receptors on the host cell, which triggers the endocytosis of the complex into the host cell. Once the virus-ACE2 complex enters the cell via endocytosis, it is exposed to a low endosomal pH. It also activates TMPRSS2, a proteolytic enzyme that cleaves the S protein within the endosome and allows the virus to enter the cytosol.

SARS-CoV-2 spike is partially folded at physiological pH, where it binds ACE2 and CR3022, and more folded at lower pH, where it still binds ACE2, but not CR3022. Schematic showing ACE2-dependent entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the pH-dependent shedding of antibodies like CR3022.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

CR3022 is an antibody that can bind the spike protein via a hidden binding site when it is present at even nanomole levels. At physiological pH, it binds at high affinity to both spike and the RBD, but with a tenfold higher affinity for the former. When the pH drops to 5.5, this is still observed, but at pH 4.5, its spike affinity becomes a thousand-fold lower very suddenly, though it still binds at high affinity to the RBD.

However, the evidence is mounting that people who recover from COVID-19 often lack high levels of neutralizing antibodies, and some have even been infected with the virus again.

The CR3022-spike protein assembly also disassembles with surprising ease. The current paper describes a model where the virus uses mobile RBDs along with the unfolding of the virus spike to achieve immune evasion by taking advantage of affinity-based mechanisms of antibody maturation.

Unfolding Enthalpy of S Protein Is Least at Physiological pH

The researchers measured the unfolding enthalpy of the spike and the facility with which it binds to the spike and the CR3022 antibody in terms of its pH. They found it to be minimum at physiological pH, about 10% that of a typical globular protein.

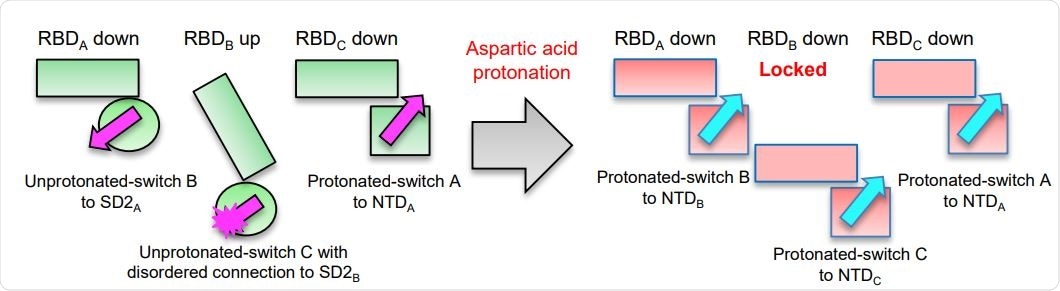

They observed a rapid tenfold increase in unfolding enthalpy at the endosomal pH, which locks the S protein into a conformation where all RBDs are facing down. This causes antibodies like CR3022 to be shed since it binds to hidden epitopes that are inaccessible in this conformation. This switch may be among a way in which the virus has developed its method of escaping immune surveillance.

The S protein can recognize ACE2 even when bound to CR3022, and the complex enters the endosome.

Asp protonation at low pH refolds switch domain locking RBD in the down position; an Asp614Gly variant has altered interactions with ACE2 and modestly impaired conformational masking. Schematic of the pH-switch locking of RBD in the down position.

CryoEM Shows Two Configurations at Different pH

The scientists in this study also carried out cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of the isolated spike protein in isolation and in complex with the ACE2 receptor. This revealed two configurations: a single-RBD-up and an all-RBD-down conformation. At the physiological pH of 5.5, the former predominates. Still, the conformational change to the latter state at the endosomal pH of 4.5 allows non-neutralizing antibodies to bind avidly and tightly to the RBD, which means that neutralizing antibodies are blocked despite a relatively high titer.

This mechanism is suggested to be responsible for immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2. A new strain of SARS-CoV-2, called the Asp614Gly, is seen to be less adept at this evasion, with markedly less enthalpy of unfolding, which allows for easy comparison of its mechanism of binding.

Possible Neutralization Methods

The researchers suggest three ways to neutralize the virus in the face of this conformational change that masks neutralizing epitopes. One is via antibodies that block the binding of the virus to ACE2, since this prevents the virus from entering the acidic endosomes and undergoing conformational change.

CR3022 is unable to neutralize the virus because of the masking of its bivalent epitope by the conformational switch at pH 4.5. This reduces its binding affinity a thousand times. Another route to overcome this effect is to use antibodies that have still higher affinity, by a few orders of magnitude, to overcome the effect produced by conformational masking at low pH.

Finally, antibodies that bind to the second spike conformation, where all RBDs are in the downstate, may neutralize the virus by locking it in this state. It is perhaps important that multiple neutralizing antibodies are now known to bind to the spike antigen in this conformation.

The investigators say, “We propose the all-down pH 4-locked conformation of the spike as a vaccine target, along the lines of what has been done to surmount evasion for other viral type 1 fusion machines, such as from RSV, HIV, and others.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources