.jpg)

Transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, isolated from a patient. Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

The study also found that children having close contact with an infected sibling was associated with an increased risk of infection.

Matthew Kelly and team say that early studies had suggested that children transmit the virus less effectively than adults, but that the current findings provide further evidence of probable child-to-child transmission among households.

The researchers also found that the clinical symptoms of infection varied markedly by age, and they warn that these differences should be considered when assessing children for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and when developing screening approaches for children in schools and childcare settings.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the server medRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

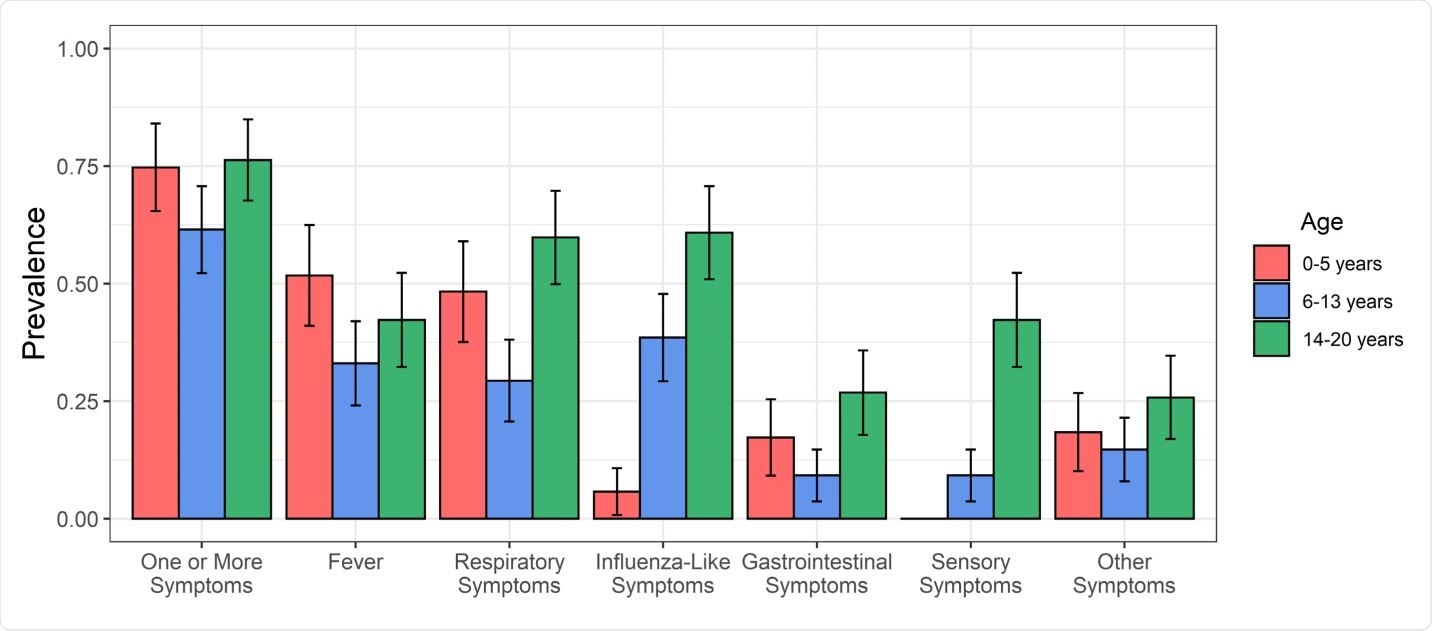

Prevalence of reported symptom complexes in 293 SARS-CoV-2-infected children by age. Age was categorized into three groups (0-5 years, 6-13 years, and 14-20 years), and the prevalence of specific symptom complexes are reported for children in each age group. Symptom complexes include respiratory symptoms (cough, difficulty breathing, nasal congestion, or rhinorrhea), influenza-like symptoms (headache, myalgias, or pharyngitis), gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea, or vomiting), and sensory symptoms (anosmia or dysgeusia). Error bars correspond to the 95% confidence interval for each symptom complex in each age group.

Researchers had thought children were less likely to transmit the virus

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic that continues to sweep the globe has now been responsible for more than 23.52 million infections and caused more than 810,000 deaths.

Current epidemiological data indicate that children are less likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2 than adults. One recent mathematical modeling study estimated that individuals younger than 20 years were about half as susceptible to the virus as adults.

“The extent to which these findings reflect differences in SARS-CoV-2 exposures among adults and children or age-related biological differences in SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility is unknown,” said Kelly and team.

So far, studies examining the clinical characteristics of infection among children have been limited by small sample sizes, cross-sectional design, and the inclusion of only symptomatic children or children that required hospitalization. The range of symptoms among children has, therefore, not been well characterized.

“Such data are critical for providers evaluating children with possible coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and for the development of effective screening strategies for children to attend schools and other congregate childcare settings,” writes Kelly and team.

What did the current study involve?

Now, in a study called the Biospecimens from Respiratory Virus-Exposed Kids (BRAVE Kids) Study, the researchers have assessed 382 children and adolescents aged less than 21 years who had a close contact infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The participants lived within the catchment area of a healthcare system in North Carolina, and the study population represents the largest pediatric cohort of non-hospitalized individuals to date.

The team took nasopharyngeal or nasal swabs at study enrollment and used a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay to test for SARS-CoV-2. Data on exposure and socioeconomic factors were collected using medical records and questionnaires that were conducted by telephone.

What did the study find?

Of 382 participants (aged an average of 9.7 years) enrolled in the study between April 7 and July 16, 2020, 293 (77%) were infected with SARS-CoV-2, and 89 (23%) were not infected.

Symptoms were reported by 206 (70%) infected individuals, with the most common manifestations being fever (42%), cough (34%), and headache (26%).

Infected children were more likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity; more than 80% of children in the cohort were Hispanic, and 59 to 62% of infected children in the study catchment area were Hispanic.

The team found that having an infected sibling was a risk factor for infection. Among 145 infected children who had an infected sibling, no close adult contacts were identified in 46 (32%) cases. Among these 46 children, the median age of infected siblings was 12 years.

Studies conducted early on in the pandemic had suggested that children transmit SARS-CoV-2 less effectively than adults, but Kelly and the team say that a growing body of evidence has since demonstrated efficient transmission from children.

“Nearly one-third of the SARS-CoV-2-infected children who had an infected sibling in our cohort did not have any other known infected close contacts, suggesting probable child-to-child transmission within these households,” writes the team.

Infected children were less likely to have asthma than uninfected children, at 6% versus 17%, which the authors suggest may be attributed to a reduced expression of the human receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) the virus uses to gain host cell entry.

“Age-related differences in the clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection”

The team also report that children aged six to 13 years were often asymptomatic (in 39% of cases) and did not have respiratory symptoms as frequently as younger children and adolescents, at 29% versus 48% and 60%, respectively.

Despite the age-related variability in clinical manifestations, the researchers found nasopharyngeal viral load did not differ by age or between symptomatic and asymptomatic children.

The duration of illness did vary markedly by age and was longer among adolescents than among children aged 0 to 5 years (7 versus 4 days) and children aged 6 to 13 years (7 versus 4 days)

“Age-related differences in the clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection must be considered when evaluating children for COVID-19 and in developing screening strategies for schools and childcare settings,” writes the team.

“Future studies are needed to elucidate the biological and immunological factors that account for the age-related differences in infection susceptibility and illness characteristics among children,” conclude the researchers.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Kelly M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infections Among Children in the Biospecimens from Respiratory Virus-Exposed Kids (BRAVE Kids) Study. medRxiv, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.18.20166835

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Hurst, Jillian H, Sarah M Heston, Hailey N Chambers, Hannah M Cunningham, Meghan J Price, Lilianna Suarez, Carter G Crew, et al. 2021. “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infections among Children in the Biospecimens from Respiratory Virus-Exposed Kids (BRAVE Kids) Study.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 73 (9): e2875–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1693. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/73/9/e2875/5952826.