A large UK study reveals that vegetarians, but not vegans, have a slightly elevated risk of hypothyroidism, raising new questions about iodine intake and the role of BMI in interpreting diet-related thyroid outcomes.

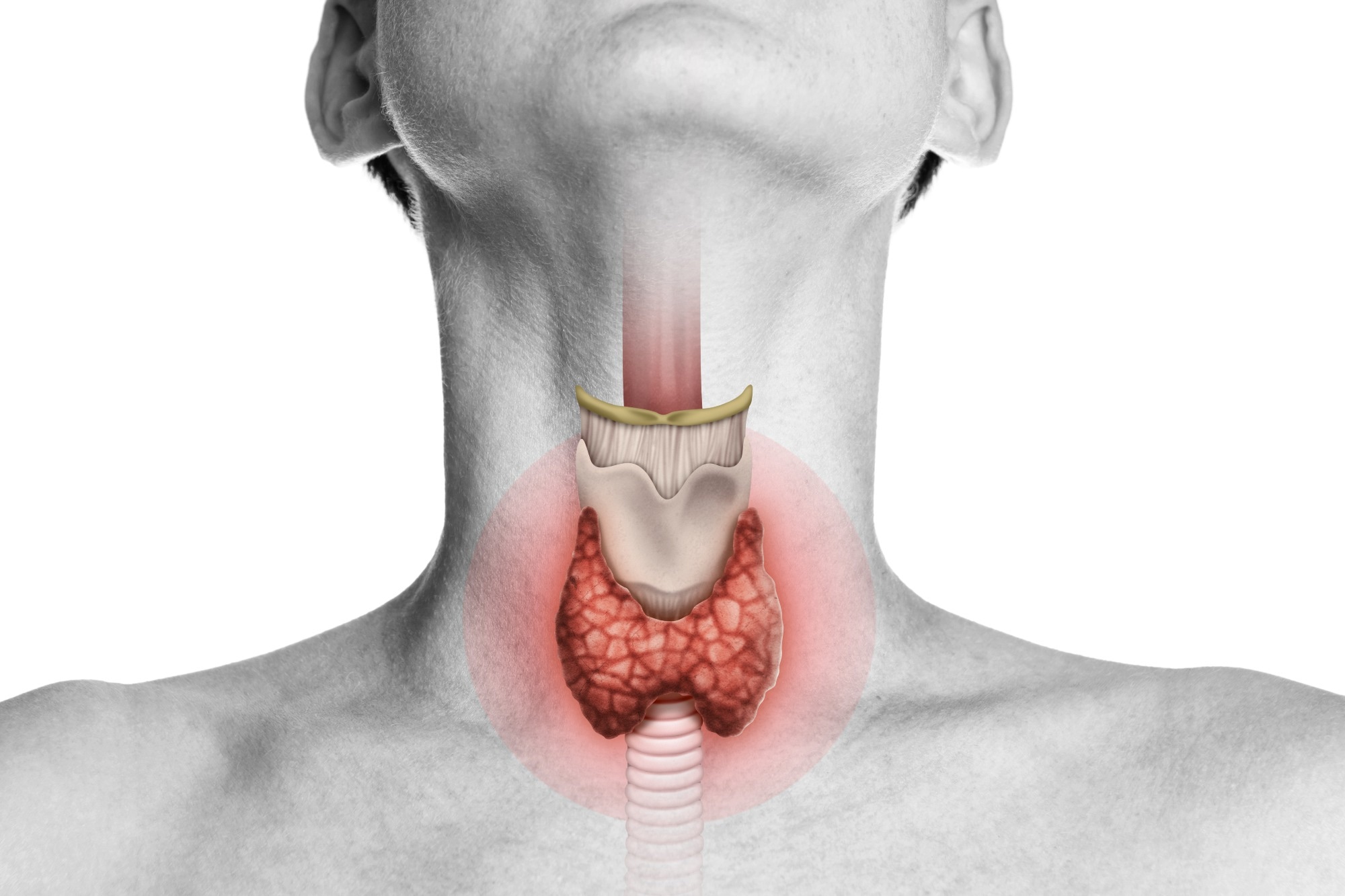

Study: Risk of hypothyroidism in meat-eaters, fish-eaters, and vegetarians: a population-based prospective study. Image Credit: SvetaZi / Shutterstock

Study: Risk of hypothyroidism in meat-eaters, fish-eaters, and vegetarians: a population-based prospective study. Image Credit: SvetaZi / Shutterstock

A study published in the journal BMC Medicine found that vegetarians may have a moderately higher risk of hypothyroidism compared to high meat-eaters, but only after accounting for body mass index (BMI). No statistically significant increase in risk was observed for vegans or pescatarians in analyses of incident hypothyroidism; however, for prevalent hypothyroidism at baseline, a statistically significant increased risk was observed for pescatarians.

Background

The popularity of plant-based diets is increasing worldwide because of documented health benefits and environmental sustainability. These diets are known to reduce the risk of various chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic diseases and cancer, as well as all-cause mortality. These health benefits are particularly noticeable when plant-based diets are composed of high-quality foods, limiting the intake of snacks, sweetened beverages, and ultra-processed foods.

One disadvantage of plant-based diets is that they often lack essential nutrients such as zinc, iron, selenium, vitamin B12, or iodine. These micronutrients play vital roles in regulating various physiological processes, including hormonal regulation.

Iodine plays a crucial role in thyroid hormone biosynthesis, and iodine deficiency can lead to goiter, thyroid nodules, and hypothyroidism. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily intake of 150 µg to achieve an adequate iodine status. For pregnant and lactating women, a daily intake of 200 µg is recommended.

Thus, the global rise in popularity of plant-based diets raises a concern about the risk of iodine deficiency and associated thyroid complications. Besides lacking sufficient iodine, certain cruciferous vegetables, such as cauliflower or kale, and soy products can reduce iodine bioavailability due to the presence of goitrogenic compounds, further increasing the risk of iodine-related hormonal complications.

Given the limited research on plant-based diets and hypothyroidism, the current study aimed to assess the risk of hypothyroidism across different dietary groups, including high meat-eaters, low meat-eaters, poultry-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians, and vegans.

Study design

The study analyzed data from 466,362 individuals from the UK Biobank, a prospective cohort study comprised of over 500,000 UK residents aged between 40 and 69. The participants were categorized into six different diet groups based on self-reported food intake data, including high meat-eaters, low meat-eaters, poultry-eaters, pescatarians (who eat fish or shellfish but not any other kind of meat), vegetarians, and vegans (strictly plant-based food eaters).

Appropriate statistical analyses were conducted to assess the risk of incident hypothyroidism across all diet groups.

Study findings

The follow-up analysis of 466,362 individuals over a period of 12 years identified 10,831 new cases of potential iodine-related hypothyroidism. The proportion of hypothyroidism cases was 2% among high meat-eaters, 2% among low meat-eaters, 3% among poultry-eaters, 2% among pescatarians, 3% among vegetarians, and 3% among vegans.

The analysis of iodine intake data from a subsample of 207,011 participants revealed that about 92% of vegans, 44% of vegetarians, and 33% of poultry-eaters failed to meet the recommended daily intake of 150 µg.

Based on sociodemographic characteristics, the study found that individuals with incident hypothyroidism are more likely to be females, have a higher body mass index (BMI; a measure of obesity), and have a lower income.

Association between diet pattern and risk of hypothyroidism

Given the significant influence of BMI in mediating the association between diet and hypothyroidism, researchers analyzed the association with and without adjustment for this influencing factor.

The analysis revealed a significant positive association between a vegetarian diet and the risk of hypothyroidism only after adjustment for BMI, a statistical approach that the authors note may introduce bias. No statistically significant association was observed for vegans, but the number of vegan participants was very small (n = 397), limiting the power to detect a difference. A positive association of baseline hypothyroidism prevalence was observed with low meat diet, poultry-based diet, pescatarian diet, and vegetarian diet. Specifically, for prevalent hypothyroidism at baseline, pescatarians had a statistically significant increased risk (OR=1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.19) after BMI adjustment.

Study significance

The study reveals that vegetarians may be at a slightly higher risk of developing hypothyroidism compared to high meat-eaters, but the effect size is modest and the association was only seen after statistically adjusting for BMI. No increased risk was found for vegans or pescatarians with respect to incident hypothyroidism, but for prevalent hypothyroidism, pescatarians did show a modestly increased risk after BMI adjustment. However, this association is significantly influenced by participants’ BMI.

Given BMI's strong influence on the study findings, researchers highlighted the importance of understanding whether BMI serves as a collider or a confounder in mediating the association between diet type and risk of hypothyroidism.

While a confounder affects both the exposure and the outcome, a collider is influenced by both. Existing evidence indicates that genetically predicted BMI can increase hypothyroidism risk, suggesting that BMI can confound the association between diet type and hypothyroidism.

Given the lower calorie intake among vegetarian participants, it is more likely that diet influences BMI than that BMI influences the effects of diet on thyroid functions. This highlights the role of BMI as a collider.

Since BMI is influenced by diet and by hypothyroidism through metabolic changes associated with the condition, researchers stated that adjusting for BMI may introduce collider bias.

Since data on thyroid health prior to BMI measurements were unavailable, researchers speculated that undiagnosed hypothyroidism or impaired thyroid function affected the BMI of participants. The authors also discuss the possibility of reverse causation, where individuals with early or undiagnosed hypothyroidism might adopt healthier or more plant-based diets in response to symptoms such as weight gain.

Overall, the study findings highlight the need for future research with data on iodine status and thyroid function prior to diagnosis. Given the role of iodine as a potential critical nutrient for vegetarians, researchers advise considering iodine supplementation to prevent the risk of thyroid-related disorders.

The authors emphasize that, as this was an observational study, causality cannot be established, and the apparent association may be due to underlying differences in BMI or other unmeasured factors.