Scientists reviewed nearly three decades of studies and found that while hormones may influence power, endurance, or coordination, the menstrual cycle’s real impact on women’s sports performance remains far from understood.

Study: Effects of menstrual cycle phases on athletic performance and related physiological outcomes: a systematic review of studies using high methodological standards. Image credit: Summit Art Creations/Shutterstock.com

Study: Effects of menstrual cycle phases on athletic performance and related physiological outcomes: a systematic review of studies using high methodological standards. Image credit: Summit Art Creations/Shutterstock.com

There has long been a debate about whether the menstrual cycle affects athletic performance in women. The evidence is conflicting, probably because of poor study design and flawed methods. A recent paper in Applied Physiology examined studies with a rigorous design to evaluate how often high standards were applied to such research and the generalizability of the findings.

Introduction

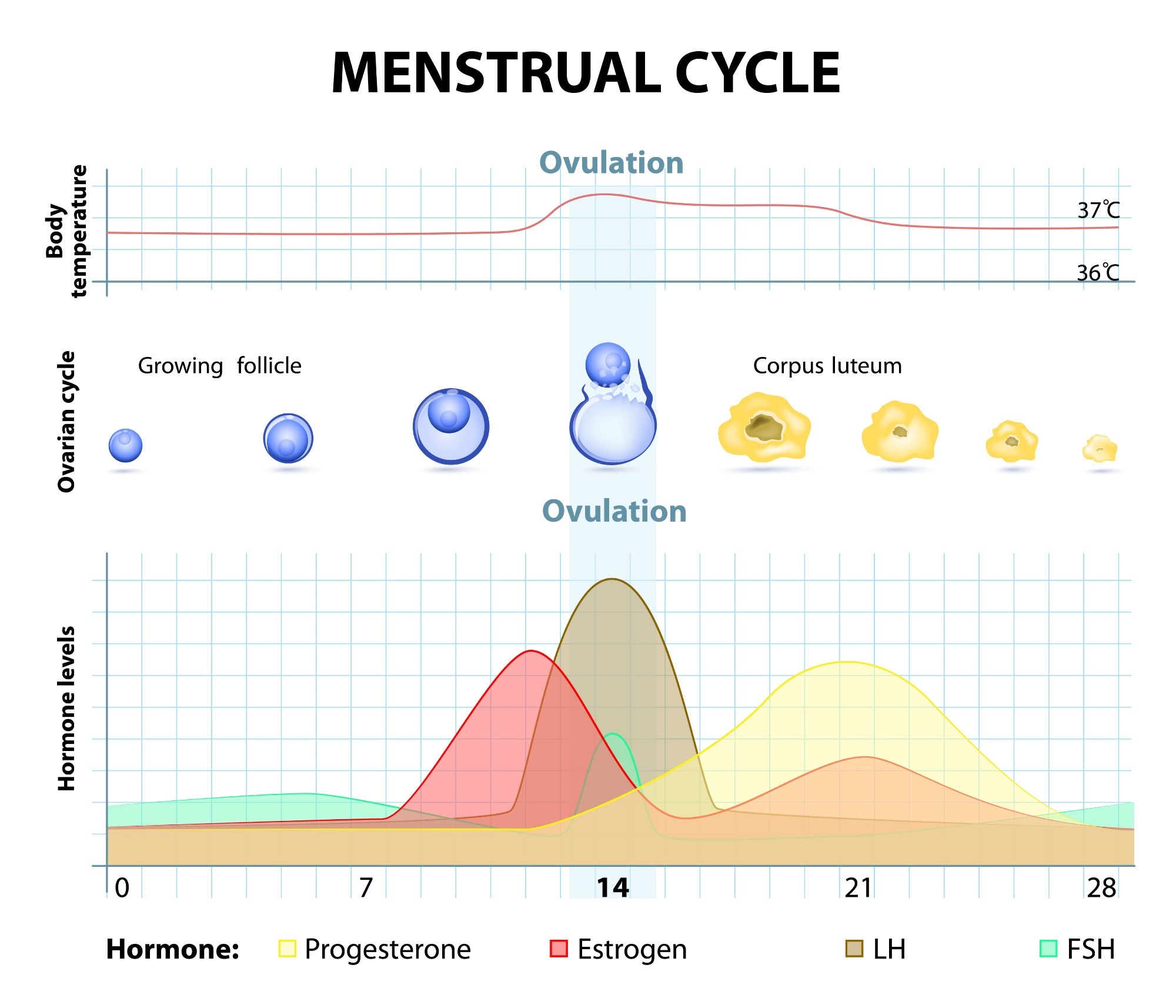

The menstrual cycle reflects cyclic changes in the hormones 17β-estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone over a period of typically 28-35 days. While these are well known to be key to female physiology and reproduction, their contribution to athletic performance remains poorly understood.

A detailed examination of the menstrual cycle reveals seven phases: the early, mid, and late follicular phase, ovulation (OV), and early, mid, and late luteal phase. However, recent methodological recommendations suggest focusing on four hormonally distinct phases (early follicular, late follicular, ovulation, and midluteal) to improve consistency across studies.

Multiple studies attempted to uncover the effects of the menstrual phase on athletic performance. Most of them failed to demonstrate any significant effects on endurance, power, or strength. Yet, some conflicting findings have been reported. These differences are often due to large differences in how different menstrual phases are classified or compared, the methods used to assign phases, and the methods used to detect ovulation. Again, some studies included only elite athletes, but others had a diverse range of women at all activity levels.

This is important since athletes performing at the top of their form have very efficient mitochondrial function, superior neuromuscular control and excellent recovery capability. These factors could perhaps make them less susceptible to the effects of hormonal changes compared to non-elite athletes, both in objective motor attributes and in subjective symptoms like dysmenorrhea.

About the study

The current study focused on using precise hormonal measurements to assign menstrual phases, comparing likes with likes. Imprecise methods like basal body temperature or the menstrual calendar increase the risk of misclassifying phases and clustering women with very different hormone concentrations. Again, such methods miss luteal phase-deficient (LPD) or anovulatory cycles.

Less than half the studies in this area measured hormone concentrations. Most studies (~80%) may have included women with anovulatory or LPD cycles for this reason, especially given that intense physical activity increases the odds of LPD cycles. This could obscure any real correlations between menstrual phase and performance.

This has led to various suggestions to standardize the research criteria. One set of widely cited recommendations proposes using four menstrual phases with characteristic ranges of E2 and P4. These comprise:

- the early follicular phase (low E2 and P4), where bleeding begins

- the late follicular phase (high E2 but low P4)

- ovulation (moderate E2 and P4 with an LH surge)

- midluteal phase (high P4 at ≥16 nmol/L, with moderate-to-high E2)

Image credit: Designua/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Designua/Shutterstock.com

The current review included 19 studies in which women's hormones were measured at different menstrual phases. Objective measures of athletic performance or performance-linked measures were used to correlate this with hormonally distinct menstrual phases.

The first group of measures assessed outcomes directly reflecting sports-related movements performed under standard conditions. The second group included physiological or biomechanical outcomes that influence or are linked to athletic performance but are not sports movements themselves. They included heart rate, maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), and muscle activation profiles.

The studies in this review included 279 women with regular menstrual cycles. The average age was 25.6 years, and each study was based on a mean of ~14 athletes. Elite athletes were underrepresented, and most studies involved recreationally active or moderately trained participants.

No study used the suggested four-phase pattern, but several used hormonal profiles to identify the menstrual phase. Almost all studies examined maximal muscle strength, mostly by isometric testing or cycle ergometers.

Study findings

Even though all studies included serum hormone measurements, most reported only the mean and standard deviation of E2 and P4 rather than the actual hormone concentrations, which does not effectively confirm menstrual normalcy.

Most studies (58%) showed that at least one performance outcome or measure was affected by changes related to the menstrual phase. However, the direction and magnitude of these effects varied. In one study, VO₂max was lower in the early follicular phase, while others found no difference. Some studies also reported lower peak power in this phase, though results were inconsistent.

Submaximal ventilation was reduced in certain comparisons of early vs. midluteal phases, while maximum and explosive strength remained largely intact.

The late follicular phase was sometimes linked to less fatigue during repeated sprints, while other studies reported reduced anaerobic sprint performance. Some researchers suggested that higher estrogen levels in this phase may improve recovery capacity, though this remains speculative.

During ovulation, neuromuscular coordination improved. This does not, however, reflect significant performance benefits.

The studies included in the review reveal significant differences, making for a heterogeneous cohort that introduces the potential for bias. This is despite all included studies using objective hormonal levels to determine menstrual phases. For example, they included sedentary participants and recreational athletes. This increases the likelihood of greater performance variability and outcome changes because of learning how to perform the given task better on repetition. Dropout rates are also likely to be higher.

Finally, not much research on elite women athletes used serum hormone measurements.

Conclusions

The review explores the benefit of using standardized, objective methods to evaluate the impact of the menstrual phase on performance. The researchers found only a few small studies that complied with the strict exclusion criteria employed here, with little interest in overall testing during the ovulation or late follicular phase.

“Overall, the included studies show little consistency regarding the effects of the MC phase on performance outcomes. The risk of bias suggests that one should critically approach conclusions about the presence or absence of MC effects.”

The difficulties associated with performing blood tests throughout the menstrual cycle may reduce participant availability. Sports scientists who perform these tests using minimally invasive techniques on the spot might enhance participation in future research.

Download your PDF copy now!