Introduction

Core principles of the diet

Health benefits

Environmental impact

Global adaptability and cultural considerations

Criticisms and challenges

Implementation strategies

References

Further reading

The planetary health diet aligns nutritional needs with environmental sustainability to reduce chronic disease risk while conserving global ecosystems. It promotes plant-rich eating patterns with limited animal products, adaptable to cultural and regional contexts.

Image Credit: Black Salmon / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Black Salmon / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

The Planetary Health Diet (PHD), also referred to as the EAT–Lancet reference diet, is an eating pattern devised by the 2019 EAT-Lancet Commission to align nutritional adequacy with the ecological limits of planet Earth. The overarching aim of the PHD is to promote and preserve human health while keeping global food production within sustainable planetary boundaries by lowering diet-related chronic disease risk and protecting long-term planetary conservation.

Core principles of the diet

The PHD is a flexitarian, health-, and environment-oriented eating pattern that emphasizes vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, unsaturated oils, and fish while limiting red meat, pork, and in more moderate amounts, poultry, eggs, dairy, potatoes, and added sugars. Seafood and poultry are considered optional in modest amounts, while dairy is occasional, and starchy vegetables such as potatoes are minimized. The PHD is intentionally flexible and culturally adaptable, as this universal “reference diet” was designed to be accepted across food traditions while maintaining sustainability goals.

The PHD prioritizes plant diversity, using seafood judiciously, and low meat consumption to reduce diet-related ecological footprints. Ultra-processed food and refined sugar intake are intended to be occasional rather than regular.2

Health benefits

The PHD supports cardiovascular and metabolic health to align individual health with environmental goals. Across large cohorts, sustainable diets like the PHD are associated with a reduced risk of major non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, as well as obesity and overweight, both of which are directly linked to metabolic disease.3

Reduced intake of red/processed meats and ultra-processed foods, both of which are key features of unhealthy eating patterns, while increasing the consumption of fiber-rich whole foods improves nutrient density and may lower the risk of certain cancers, particularly colorectal cancer, by reducing exposure to carcinogens from processed/red meat, including nitrites/nitrates and compounds formed during high-temperature cooking, as well as chronic inflammation and hormonal drivers of disease. While evidence from meta-analyses suggests a protective association, certainty is rated as low due to heterogeneity and potential residual confounding. The PHD encourages balanced nutrient intake without relying on animal products by emphasizing diverse plant foods and limiting red meat.3

Environmental impact

The PHD reduces demand for resource-intensive products and encourages efficiency along supply chains. Furthermore, the PHD lowers climate impacts and pressure on croplands and irrigation, thereby conserving water and preventing soil depletion. The magnitude of these benefits depends on specific food choices within the PHD framework and regional agricultural practices, as some healthy foods, such as certain nuts or greenhouse-grown vegetables, can have relatively high environmental footprints.

The PHD and other sustainable diets also support biodiversity and soil health to reduce incentives for deforestation and monocultures. Healthier crop rotations, reduced fertilizer loads, and a decrease in total manure production alongside better manure management can also improve soil structure and nutrient cycling, limiting erosion and runoff.4

Overall, the PHD is an eating pattern that simultaneously advances human health and environmental stewardship. These benefits include lower emissions, restrained land and water use, as well as the development of production systems that provide long-term protection for biodiversity and soils.4

Image Credit: KraArkaR / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: KraArkaR / Shutterstock.com

Global adaptability and cultural considerations

The EAT-Lancet Commission explicitly sets intake ranges and targets for major food groups to allow countries to adapt the PHD to local crops, cuisines, and supply chains while staying within health and environmental limits.

This adaptability is crucial, as national dietary quality varies widely. For example, Mediterranean nations align closely with PHD principles through higher intakes of vegetables, fruits, and unsaturated fats, whereas North America and Latin America/Caribbean cuisines incorporate more red/processed meat and added sugars.5

Effective adaptation must also consider affordability and food-system incentives. In low-income settings, limited purchasing power often causes consumers to favor refined staples, starchy vegetables, and cheap added fats. Comparatively, in high-income settings, policies that favor commodity crops lead to lower meat prices and more expensive fruits/vegetables.

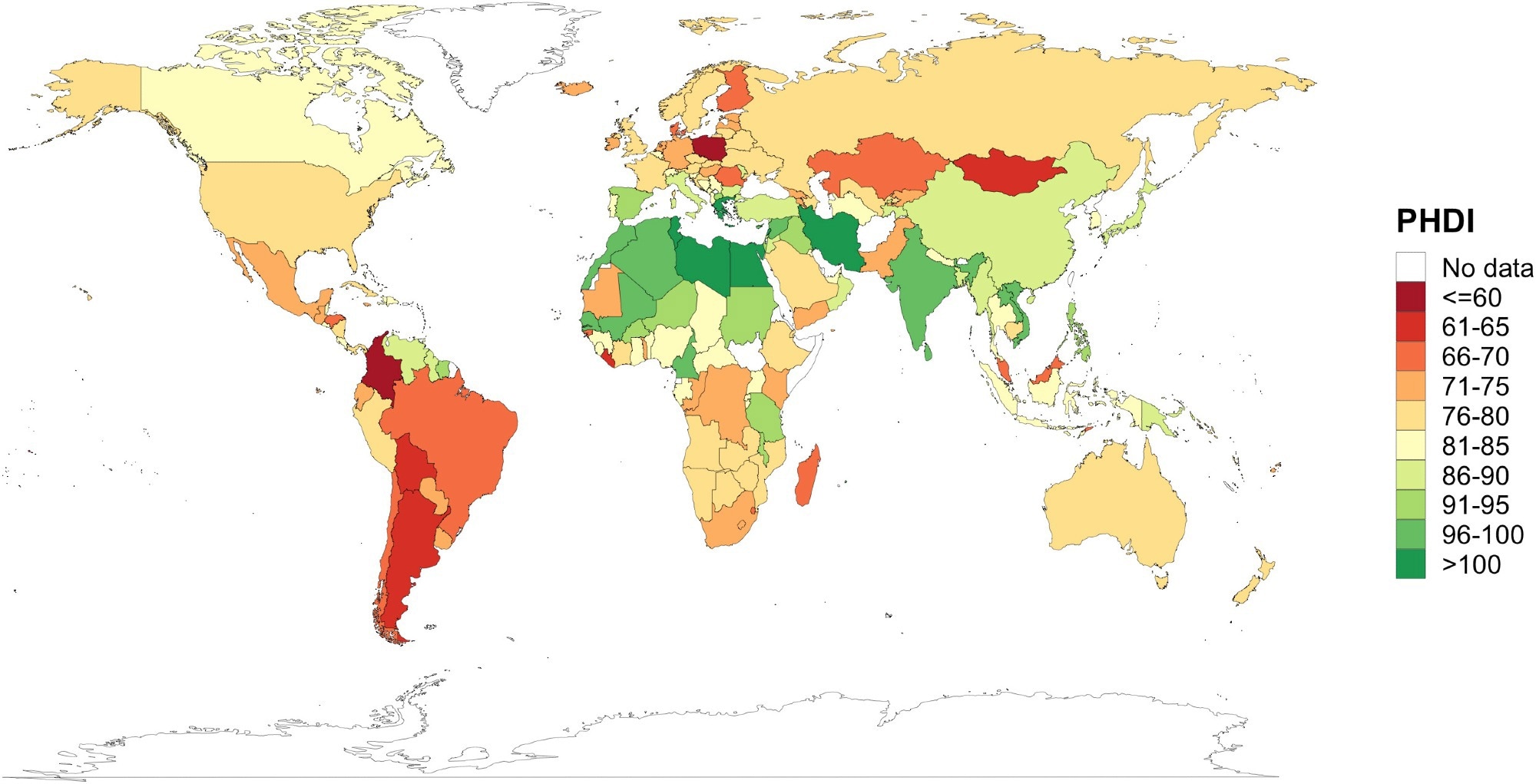

Lebanon, Tunisia, Greece, Egypt, Libya, and Cyprus report some of the highest PHD Index (PHDI) scores (based on 2024 data; global average adherence is about 85 out of 140), which reflects plant-rich patterns with low added sugars and saturated fats. Conversely, several Latin American countries, including Chile, Honduras, Argentina, Bolivia, and Colombia, rank among the lowest PHDIs due to higher red meat and sugar intake. India scores higher partly because cultural and economic factors limit red-meat intake; however, dairy intake is relatively high, and trans-fat regulation remains a challenge.5

Geographic distribution of the PHDI for people aged over 20 in 171 countries/territories in 2018. The PHDI ranges from 0 to 140, where 0 indicates nonadherence to the Planetary Health Diet and 140 indicates perfect adherence. PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index.5

Geographic distribution of the PHDI for people aged over 20 in 171 countries/territories in 2018. The PHDI ranges from 0 to 140, where 0 indicates nonadherence to the Planetary Health Diet and 140 indicates perfect adherence. PHDI, Planetary Health Diet Index.5

Criticisms and challenges

In low-income settings, limited purchasing power causes consumers to purchase cheap staples and added fats. In some areas, legumes and pulses, the main PHD protein sources, may also be expensive or seasonally unavailable, further limiting adherence. These food environments may also lack reliable cold storage and hygiene for indigenous produce, thereby reducing access to diverse plant-based foods.5,6

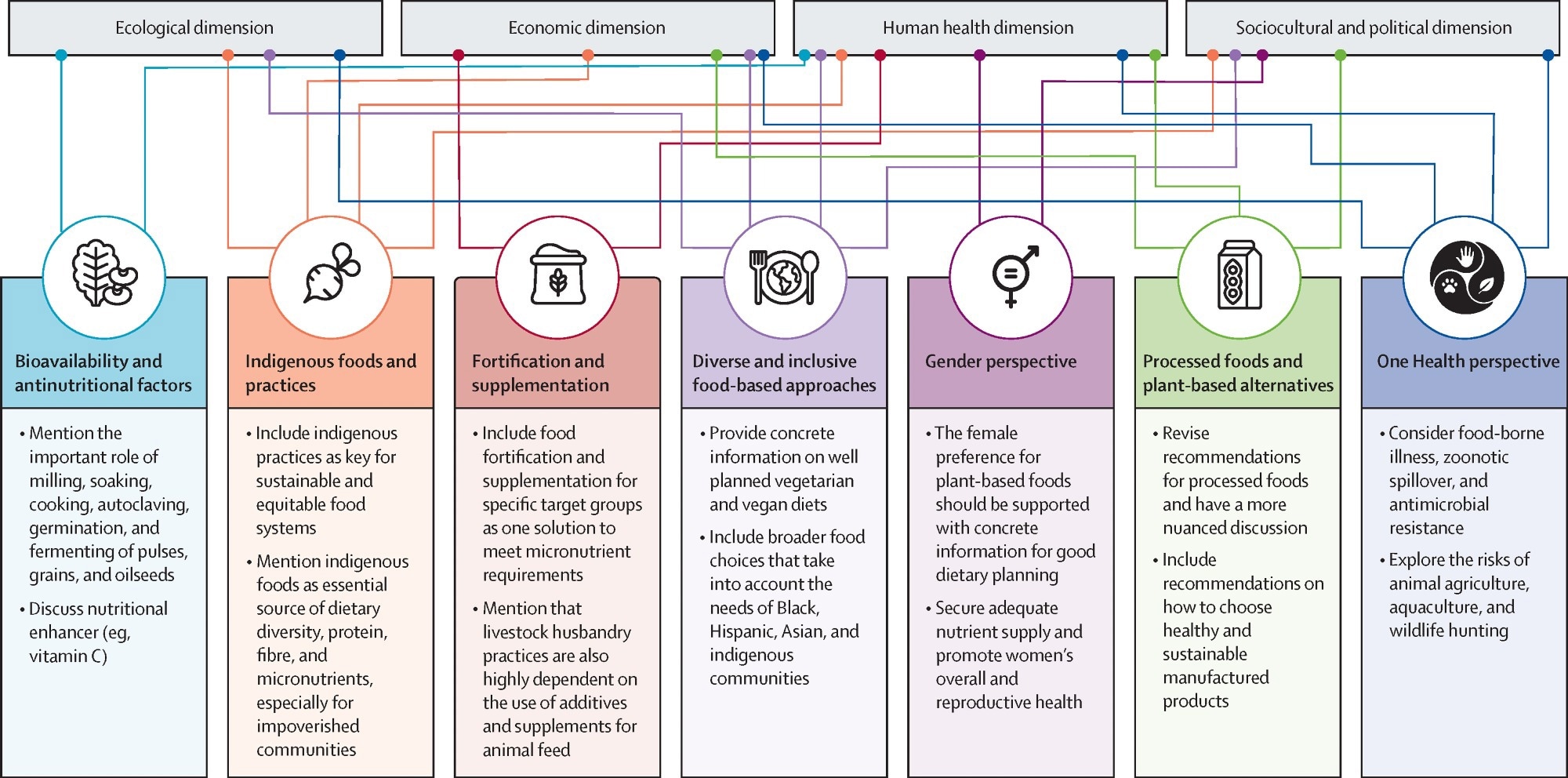

Current shortfalls of the planetary health diet from a plant-forward perspective6

Current shortfalls of the planetary health diet from a plant-forward perspective6

Nutrient adequacy is a concern, as low levels of calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 can arise if plant-forward patterns are not carefully planned. To overcome these limitations, certain strategies like fortification, biofortification, and targeted supplementation can be adopted.5,6

Agricultural policies in many high-income countries maintain a low cost for red meat, whereas fruits/vegetables are comparatively expensive, which strongly influences consumption patterns. These feasibility constraints, unresolved nutrient-adequacy concerns, stakeholder resistance, and policy/infrastructure gaps prevent the large-scale adoption of the PHD, which must be addressed through locally adapted planning, stronger public policy, and dietary guidance.5,6

Image Credit: Anggalih Prasetya / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Anggalih Prasetya / Shutterstock.com

Implementation strategies

Governments are encouraged to incorporate front-of-pack labels that clearly guide consumers toward healthier and low-impact foods, as these are more effective than dense numeric back-panel labels. National dietary guidelines should also integrate sustainability considerations to better guide school meals and industry reformulation.7

The agricultural sector must transition away from subsidized staples toward diversified production of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts. These efforts can improve affordability and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while investing in irrigation, energy, roads, storage, and cold chains reduces loss, costs, and price volatility for perishable, nutrient-dense foods. Reducing food waste along the supply chain is also a key strategy to improve both environmental and nutritional outcomes.7

Implementation of these strategies is most effective when community-led efforts are supported by local governments to improve access. A supportive political environment that encompasses commitment, coherent policy packages, social mobilization, and accountability, are imperative to sustain change.7

References

- Huang, S., Hu, H., & Gong, H. (2024). Association between the Planetary Health Diet Index and biological aging among the US population. Frontiers in Public Health 12. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1482959, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1482959/full

- Guzmán-Castellanos, K. B., Neri, S. S., García, I. Z., et al. (2025). Planetary health diet, mediterranean diet and micronutrient intake adequacy in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. European Journal of Nutrition 64(4). DOI:10.1007/s00394-025-03657-2, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-025-03657-2

- Kasper, M., Al Masri, M., Kühn, T., et al. (2025). Sustainable diets and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 83. DOI:10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103215, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(25)00147-6/fulltext

- Kyttä, V., Ghani, H. U., Pellinen, T., et al. (2025). Integrating nutrition into environmental impact assessments reveals limited sustainable food options within planetary boundaries. Sustainable Production and Consumption 56;142-155. DOI:10.1016/j.spc.2025.03.018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352550925000685

- Gu, X., Bui, L. P., Wang, F., et al. (2024). Global adherence to a healthy and sustainable diet and potential reduction in premature death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121(50). DOI:10.1073/pnas.2319008121, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2319008121

- Klapp, A. L., Wyma, N., Alessandrini, R., et al. (2025). Recommendations to address the shortfalls of the EAT–Lancet planetary health diet from a plant-forward perspective. The Lancet Planetary Health. 9(1). DOI:10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00305-X, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(24)00305-X/fulltext

- Fanzo, J., & Miachon, L. (2023). Harnessing the connectivity of climate change, food systems and diets: Taking action to improve human and planetary health. Anthropocene. 42. DOI:10.1016/j.ancene.2023.100381, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213305423000140

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 17, 2025