Introduction

Germ layers in animal development

Diploblastic animals

Triploblastic animals

Key differences between diploblasts and triploblasts

Evolutionary significance

Limitations and ongoing debates

Conclusion

References

Further Reading:

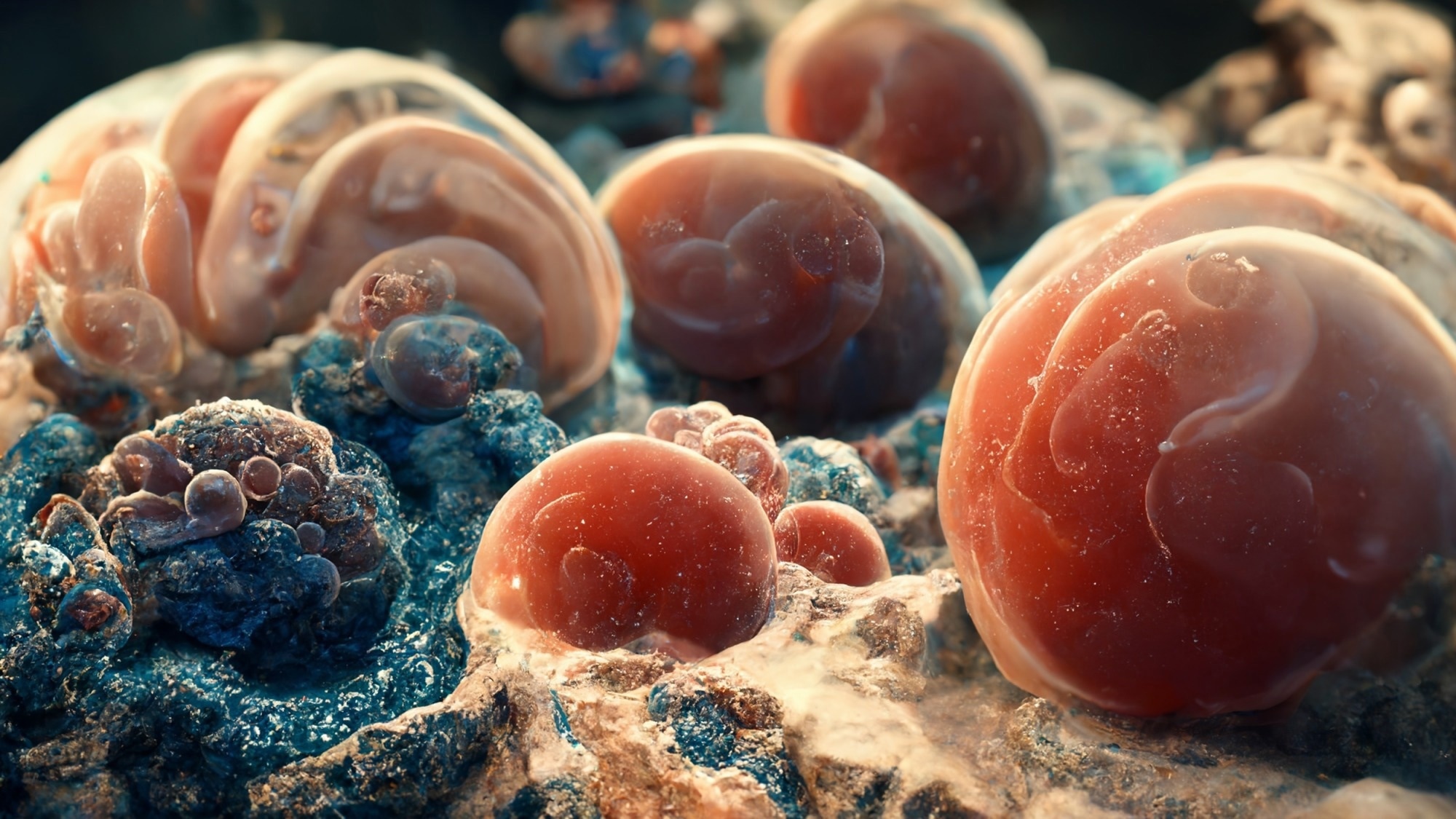

This article explains how diploblastic and triploblastic animals differ in embryonic germ layer organization and why these differences matter for body structure and function. It highlights how the evolution of the mesoderm enabled greater biological complexity, diversification, and ecological success.

Image credit: Sirinneon/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Sirinneon/Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Embryonic germ layers are the fundamental organizing principle in animal development. They provide the structural basis from which tissues and organs arise. During early embryogenesis, cells divide to form separate layers that establish the blueprint of the body plan. Animals developed from two primary germ layers are called diploblasts, and animals formed from three germ layers are called triploblasts.

The evolutionary emergence of a third germ layer, the mesoderm, represents a major developmental transition rather than a linear “reward” of evolution. It enabled animals to develop complex, specialized organs, muscles, and internal systems. Understanding diploblasty and triploblasty, therefore, offers key insights into how developmental mechanisms shape animal form and how increasing biological complexity evolved over time.1

This article explains the formation, differences, and evolution of diploblastic and triploblastic animals.

Germ layers in animal development

Germ layers in animal development are sheets of cells that form early in embryogenesis and act as the foundation for all tissues and organs. They are formed during gastrulation, an early developmental phase in which cells rearrange and migrate to establish organized layers.

In triploblastic animals, three primary germ layers are formed. The outer layer, called the ectoderm, develops into the epidermis and the nervous system, while the middle layer, the mesoderm, develops into muscles, connective tissues, blood vessels, and many internal structures. The endoderm forms the lining of the digestive tract and associated organs such as the liver, pancreas, and lungs, establishing essential internal systems.2,3

Diploblastic animals

Diploblastic animals develop from two primary germ layers, the ectoderm and endoderm, which form during early embryogenesis. These layers are separated by a gelatinous extracellular matrix, the mesoglea, which is largely acellular and lacks the organization of true mesodermal tissues. As a result, diploblasts exhibit relatively simple body organization with limited tissue differentiation.

They typically show radial symmetry, allowing them to respond to environmental stimuli from all directions. Examples include cnidarians such as jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals, as well as ctenophores. Although some diploblastic lineages possess muscle-like or mesoderm-associated cell types, these are not considered homologous to the mesoderm of triploblasts, reflecting an early stage in the evolution of animal body plans.1

Triploblastic animals

Triploblastic animals develop from embryos with three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and an additional middle layer, the mesoderm. The formation of mesoderm represents a major evolutionary transition, enabling animals to develop complex body architectures and organ systems.

The mesoderm gives rise to muscles, blood vessels, connective tissues, skeletal elements, kidneys, and many internal organs, providing structural support and enabling efficient physiological integration. Bilateral symmetry and internal organ compartmentalization are characteristic features of triploblastic organization. Consequently, triploblasts include the vast majority of animal phyla and encompass all bilaterian animals.1

Key differences between diploblasts and triploblasts

The embryonic structure and developmental potential of diploblasts and triploblasts differ markedly. Diploblasts possess only two primary germ layers separated by a non-mesodermal mesoglea. Their tissues are relatively simple, lacking true mesoderm-derived organs, and their body plans are generally radially symmetric.1

In contrast, triploblasts develop a mesoderm that enables the formation of complex tissues such as muscles, connective tissues, and circulatory systems. This additional layer allows the development of internal body cavities, true organs, and advanced coordination of physiological functions. Triploblasts are typically bilaterally symmetric and exhibit greater developmental plasticity, supporting diverse body plans and lifestyles.

These structural differences contribute to ecological diversification: diploblasts generally occupy simpler niches, while triploblasts dominate animal diversity due to their greater functional and morphological complexity.1

Evolutionary significance

The transition from diploblastic to triploblastic organization represents a major milestone in animal evolution. Diploblastic animals, with only two germ layers, are constrained in tissue differentiation and functional complexity. The emergence of a third germ layer expanded developmental potential by enabling the evolution of musculature, circulatory systems, and complex organ interactions. This transition facilitated active locomotion, internal transport of nutrients, and more efficient physiological integration among tissues.1,3

Triploblasty is also closely associated with the evolution of bilateral symmetry and internal compartmentalization, traits linked to directional movement and increasingly complex behaviors. These innovations enabled animals to exploit new ecological opportunities, driving extensive adaptive radiation and the long-term dominance of triploblastic lineages in modern ecosystems.1,3

Limitations and ongoing debates

Despite its usefulness, the diploblast–triploblast distinction remains a subject of debate in evolutionary biology. Uncertainty persists regarding the phylogenetic relationships among early-diverging animal groups such as cnidarians, ctenophores, sponges, and placozoans. These ambiguities complicate interpretations of whether diploblasty or triploblasty represents the ancestral condition.

Some researchers question the strict classification into diploblasts and triploblasts, noting that germ layer homology and tissue differentiation vary across lineages. In particular, the evolutionary origin of the mesoderm and the possibility of intermediate or transient tissue states remain unresolved. Conflicts between genomic, developmental, and morphological data continue to refine models of early animal evolution.1,3

Conclusion

The comparison between diploblastic and triploblastic animals illustrates how differences in embryonic germ layer organization shape animal form, function, and evolutionary potential. Diploblasts are characterized by two primary germ layers and relatively simple, radially symmetric body plans. Triploblasts possess an additional mesodermal layer that enables the development of complex tissues, true organs, bilateral symmetry, and integrated physiological systems.

These developmental innovations underpin major evolutionary transitions, including increased mobility, ecological diversification, and the emergence of complex animal life. Understanding germ layer organization remains central to explaining the evolutionary origins of animal diversity.

References

- Stuart A. Newman. (2016). ‘Biogeneric’ developmental processes: drivers of major transitions in animal evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 371 (1701). DOI:10.1098/rstb.2015.0443, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/rstb/article/371/1701/20150443/22957/Biogeneric-developmental-processes-drivers-of

- Kiecker, C., Bates, T., & Bell, E. (2016). Molecular specification of germ layers in vertebrate embryos. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73(5). 923-947. DOI:10.1007/s00018-015-2092-y, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00018-015-2092-y

- Burton, P. M. (2008). Insights from diploblasts; the evolution of mesoderm and muscle. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 310(1). 5-14. DOI:10.1002/jez.b.21150, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jez.b.21150

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 4, 2026