A whiplash injury is a common soft-tissue injury that may result in neck pain and other symptoms like headaches and arm pain.

Most commonly whiplash injuries are a result of motor vehicle collisions, although they may also be caused by slips, trips or falls.

Whiplash is a mechanism of injury where the neck is over-extended. The symptoms experienced following a whiplash injury are referred to as Whiplash Associated Disorders (WAD).

Many people recover quickly from this type of injury but a substantial proportion will go onto develop chronic WAD.

The proportion of people who suffer on-going problems following a whiplash injury ranges from 16% to 71% but this depends on where these people are studied and how you measure their symptoms.

Here in the UK it is a highly controversial subject as increasing numbers of insurance claims push up insurance premiums and there are reports of fraudulent claims.

What causes whiplash?

A person sustains a whiplash injury when they are shunted or jolted so that their head suddenly moves backwards and then possibly forward. It is often referred to as an acceleration-deceleration injury to the neck.

The sudden movement of the head and neck result can result in a soft tissue injury to the neck region. It should be noted that not all people who have a whiplash injury will develop WAD – another factor that adds to the controversy and uncertainty of this condition.

How many people suffer from whiplash?

In 2002 it was estimated that 250,000 whiplash injuries occur each year in UK. A recent population based survey conducted on behalf of the UK Association of Personal Injury Lawyers reported that 1 in 100 people sustained a whiplash injury in 2012.

The British Association of Insurers report that around 570,000 submit a claim related to a whiplash injury in 2011. Whichever figure you look at, it is a common problem.

Estimated costs to the UK economy were £2.5 billion per annum in 1990 rising to £3.1 billion per annum in 2002. Costs arise from National Health Service (NHS) treatment costs, social security payments, lost productivity due to work absence and damage to property.

What are the current types of treatment available for whiplash?

In the UK, individuals who experience a whiplash injury often visit the Emergency Department (ED) or their general practitioner immediately following their injury.

We know from survey work carried out by our research team that in the ED, first line treatment usually consists of basic advice about exercises and prescription of pain-relieving medications.

For individuals who continue to have problems, physiotherapy, chiropractics and osteopathy are common treatments. The Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial was commissioned because of a lack of evidence to support these types of interventions.

How do more costly intensive treatments differ from usual care?

In the context of our research, usual care referred to the control treatment delivered in the ED. Usual care meant that the EDs allocated to this arm of the study continued with their current approach to managing patients with whiplash injuries.

The EDs allocated to the active management arm of the study were trained to provide active management advice based on the “The Whiplash Book”. Patients received detailed advice about managing their injury, prognosis and returning to activities supplemented by high quality written material.

How did your research evaluate these two types of treatment?

This research was led by Professor Sallie Lamb who is based at the University of Oxford. We conducted a two-step Randomised Controlled Trial evaluating treatments in the Emergency Department for acutely injured people and, for those people with on-going problems, we evaluated the effectiveness of physiotherapy in the second step.

In step one, we evaluated ED treatments and compared usual care and an active management consultation as described above. Step one was cluster randomised meaning that the EDs were randomised rather than the patients. Patients attending the ED with a whiplash injury received treatment as well as information about the study and were asked if they were happy to be contacted by the study team.

We then wrote to these patients inviting them to take part in the study and to return a baseline questionnaire. Patients were enrolled in the study when they returned the baseline questionnaire.

They received follow up postal questionnaires at 4, 8 and 12 months after their attendance at the ED. The primary outcome was disability measured by the Neck Disability Index and secondary outcomes included health related quality of life and days off work. We also collected information on health resource use.

Participants with on-going problems 3 weeks post injury were able to self-refer to Step 2 of the study where we compared two different physiotherapy treatments. Eligible participants were individually randomised to receive a package of physiotherapy (up to 6 sessions) or one session of advice with a physiotherapist.

The physiotherapy package was well aligned with the UK Chartered Society of Physiotherapy guidelines for the management of WAD so we were confident we were testing best practice physiotherapy.

The advice session re-iterated the advice contained in the ED information sheet and there was an opportunity for the participant to ask questions.

What did your research find?

3851 patients agreed to take part in Step 1 and 70% of study participants provided follow up data at 12 months. On average, participants did not report any added benefit from the active management approach despite the fact this provided them with additional information and “The Whiplash Book”. Both groups reported the same level of disability and health related quality of life at follow up.

We have thought a lot about why the active management approach did not improve outcomes. We interviewed a small group of participants about their experiences in the study and this has provided some insight.

There were two potential reasons that the active management approach did not improve outcomes. Firstly, interview participants reported that the verbal advice given in the ED was inconsistent (some participants reported receiving advice to exercise but others were told to rest) in both arms despite the clinician’s in the active management approach receiving additional training.

Secondly, although, The Whiplash Book was much better received by patients compared to the usual care advice leaflets and participants spoke favourably about the advice it contained, it was apparent that this advice was not always acted on (e.g. do the exercises). So, better quality written advice does not necessarily result in behavioural change that could potentially improve outcomes.

In step 2, we randomised 599 participants and 80% of these participants provided follow up data at 12 months. This data showed that, on average, there was a modest benefit from the physiotherapy package at 4 months compared to the advice session but the difference did not persist over time.

By 8 and 12 months both groups reported the same level of disability and health related quality of life. However, one benefit from the physiotherapy package was that it resulted in 4 fewer days lost from work over the 12 month period. We hypothesise that repeated contact with the physiotherapist encouraged them or reassured them they could return to work.

The cost of the interventions was assessed from an NHS perspective. The active management consultation in the ED cost more to deliver with no added benefit. The physiotherapy package also cost more to deliver than the advice session and, although, the physiotherapy intervention provided initial benefit to participants it was not assessed to be cost-effective from an NHS perspective overall.

What impact do you think your research will have?

Providing patients with more information about self-management and encouragement to return to activity in the ED environment did not improve their recovery. The study recommends that usual care in EDs should continue.

We conducted a pragmatic trial of physiotherapy within the NHS and showed that it did not provide long-term benefit to patients. Based on the current evidence, we would not recommend a package of physiotherapy care for these patients.

Instead, an advice session should be offered to encourage patients to self-manage. This raises the question about the way physiotherapy is currently provided for these patients and will hopefully lead physiotherapy services to evaluate their practices more closely.

Another important finding was that 20% of participants in Step 1 and 30% of participants in Step 2 had on-going problems at 12 month follow up. These findings will hopefully stimulate the research and clinical communities to think about new ways to improve the early management of WAD as current approaches are inadequate for many patients.

What do you think the future holds for whiplash treatment?

We know that there is a lot of room for improvement in the effectiveness of treatments for WAD. Research into painful conditions such as WAD still has a long way to go in terms of understanding the complexities of how biological, psychological and social factors interact to affect individuals’ health states.

There are new avenues to explore based on the findings from prognostic studies. High pain intensity is consistently reported as a risk factor for poor outcome. Trials looking at medication to reduce pain early after injury could be considered as there is little research in this field.

Psychological factors (such as distress, unhelpful beliefs about pain, catastrophising, low self-efficacy & low expectations of recovery) are associated with poor outcome independently of baseline pain and disability.

Focused cognitive behavioural interventions may also be of benefit to address these factors but this has not been assessed in an acute population and requires further research.

Compensation remains a hot topic of discussion in the area of whiplash injuries but it is actually quite difficult to research. It is very difficult to do a randomised controlled trial so you are left with observational studies which are open to bias so new innovative ways to assess the impact of compensation on recovery would be helpful.

Finally, some people feel that it is a public health issue and that public perceptions around whiplash injuries need to be changed. That is another avenue of possible research.

Would you like to make any further comments?

We would like to acknowledge the funders of our research the National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme.

Where can readers find more information?

They can find our research paper here: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2812%2961304-X/abstract

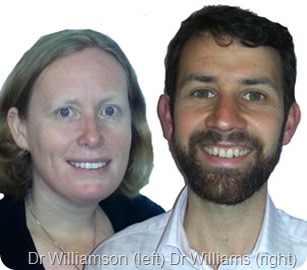

About Dr Mark Williams and Dr Esther Williamson

Dr Mark Williams and Dr Esther Williamson worked with Professor Sallie Lamb to conduct the Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial at the University of Warwick. Professor Lamb currently works at The University of Oxford and The University of Warwick.

Dr Mark Williams and Dr Esther Williamson worked with Professor Sallie Lamb to conduct the Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial at the University of Warwick. Professor Lamb currently works at The University of Oxford and The University of Warwick.

Mark Williams is a Research Fellow at the University of Warwick. He completed his PhD in 2011 which looked at the role of movement in recovery from Whiplash injury. Prior to this he worked as a physiotherapist in the NHS.

Esther Williamson is a Research Fellow at the University of Warwick since 2004. She was awarded her PhD in 2011. Prior to taking up a post in research she was a Clinical Specialist Physiotherapist working in the NHS for over 10 years.