The emergence of the novel coronavirus outbreak in December 2019 was followed by its spread on a global scale unparalleled in the last 100 years. At present, it has claimed over 322,000 lives the world over, with over 4.88 million cases having tested positive.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) sequence was first uploaded in early 2020, but as of now, over 17,000 genomes have been sequenced from viral strains isolated all over the world. This allows for rapid RNA screening in human tissues as well as environmental samples.

.jpg)

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round gold objects) emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes COVID-19. The virus shown was isolated from a patient in the U.S. Credit: NIAID-RML

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Detection of Virus in Human Blood or Blood Cells

The current study by researchers in Cairo, Egypt, and published on the preprint server medRxiv* was designed to test for the presence of the virus in human blood or any blood cells, which could allow the virus to hide from the immune system or to be trafficked to other organs. It is especially relevant given some (doubtful) reports that the virus could infect lymphocytes.

Other scientists have claimed that the virus perhaps attacks hemoglobin, or that it is to be found in the blood of infected patients, or the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs), as is the case with other infectious viruses like hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HIV.

The current study, therefore, used computational analysis on three genome sequences from PBMCs from active COVID-19 patients, three from healthy donor PBMCs, and two from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) from patients. They found that traces and large amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA were found in the PMBCs and BAL, respectively.

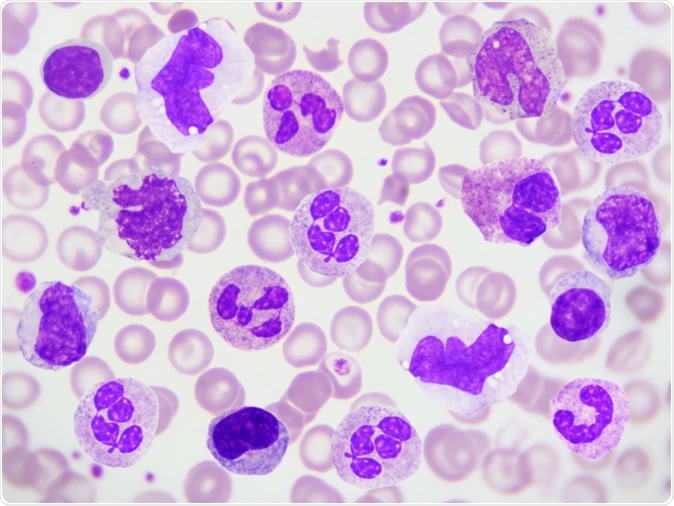

White blood cells in peripheral blood smear. Image Credit: Jarun Ontakrai / Shutterstock

Viral RNA in Blood Cells

The results showed that the BAL and PBMC samples were widely separated, as expected, while the PBMCs from healthy and patient samples were slightly separated for the most part. Viral RNA was present in all the BALF sequences at 2.15% of the total reads (median). The PBMC of one patient also showed two reads that matched the SAR-CoV-2 protein and surface glycoprotein.

Earlier studies showed that with the use of RT-PCR, CoV-RNA was found in plasma samples from COVID-19 patients, but they did not confirm the presence of infectious viral particles in the blood. For this reason, they called their finding ‘RNAemia’ rather than viremia.

The current report is, however, the first to show the presence of viral RNA in PBMC. In fact, a prior study that examined RNA isolated from PBMC made it clear that no viral sequences were found.

The researchers used high-throughput sequencing, which has been demonstrated to be effective in identifying and measuring the number of viral particles in the blood. For this reason, they used this method to do a comprehensive search for viral RNA sequences within the only public dataset now available. They found that viral RNA was present within all BAL samples, at a concentration of 2.15% of the total RNA. Two RNA reads corresponded to the SARS-CoV-2 genome. However, as expected, the PBMC from the controls did not contain any RNA.

Implications

Though the amount of viral RNA is small, it is undoubtedly that of the SARS-CoV-2. One of the reads encodes a polyprotein, which takes part in viral transcription and replication, and which is the largest of the coronavirus proteins. Another encoded the spike protein, which is responsible for the viral entry into human cells that carry the ACE2 molecule receptor.

The possibility is always alive that the viral RNA reads are the result of cross-contamination or one barcode bleeding into another. However, this is a rare chance because none of the control samples showed similar correspondence. Again, they could be the result of virus sampling by antigen-presenting cells, especially dendritic cells, or virus presentation to T cells, which form part of the PBMC population.

There is a third possibility, which can be analyzed only with a much larger number of samples. This is that the virus may have been engulfed either on purpose or by accident by one of the PBMCs. This occurrence could be one mechanism for chronic SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the theory must be tested rigorously.

One hypothesis that is not supported by the current experiment is T cell targeting by the virus in vivo, which arose from an earlier cell culture experiment using pseudotyped viruses.

The current experiment will help to take the present understanding of the progress and replication of the SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources