Introduction

What is trained immunity?

Diet as a modulator of innate immune memory

What are β-glucans?

Cereal β-glucans and immune training

Mushroom β-glucans and innate immune reprogramming

Dietary patterns and immune regulation

Practical, evidence-aligned takeaways

Important considerations

References

Further reading

Emerging research reveals how specific dietary components may reshape innate immune memory at the level of metabolism and chromatin, offering new insight into the biological interface between nutrition and immune resilience.

Image Credit: Arturs Budkevics / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Arturs Budkevics / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Trained immunity refers to the ability of the innate immune system to build a form of memory after infection or vaccination to confer protection against subsequent heterologous (non-specific) challenges rather than antigen-specific recall.1,2 First formally described following observations with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination,1,2 trained immunity is mediated by epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming of innate immune cells and, in some cases, their bone marrow progenitors.2 This article explores how diet, especially β-glucan-rich foods, may influence trained immunity through metabolic–epigenetic remodeling, while emphasizing that most supporting data derive from in vitro systems and animal models rather than long-term human intervention trials.2–5

What is trained immunity?

Unlike transient innate immune activation, trained immunity is characterized by long-lasting but reversible functional reprogramming of monocytes, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).1,2 This reprogramming enhances or suppresses inflammatory responses independently of antigen-specific receptors.1

Mechanistically, trained immunity involves enrichment of activating histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac at promoters and enhancers of inflammatory genes,1,2 alongside metabolic rewiring toward aerobic glycolysis, cholesterol synthesis, and activation of the mevalonate pathway.2 The mevalonate pathway has been shown to play a central role in β-glucan–induced trained immunity through mTOR activation and downstream epigenetic effects.2

Accumulation of TCA cycle intermediates, such as fumarate and succinate, can inhibit histone demethylases, thereby stabilizing activating chromatin marks.2 Additionally, β-glucan–induced training involves an IL-1β–dependent autocrine amplification loop that reinforces metabolic and transcriptional reprogramming.1,2

Importantly, trained immunity is distinct from endotoxin tolerance, a hyporesponsive state following repeated lipopolysaccharide exposure2. Thus, innate immune memory can produce either hyperresponsive or hyporesponsive phenotypes depending on stimulus type and context.2

Diet as a modulator of innate immune memory

Nutrients and diet-derived metabolites engage pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and influence immunometabolism. Experimental evidence demonstrates that dietary exposures can reprogram HSPCs in the bone marrow, altering downstream myelopoiesis and trained immunity phenotypes.2 For example, Western-style diets induce NLRP3-dependent innate immune reprogramming that persists beyond dietary normalization.2

However, whether habitual human dietary patterns reproducibly induce durable trained immunity phenotypes comparable to those observed with microbial ligands such as β-glucan or BCG remains incompletely established.2,3

What are β-glucans?

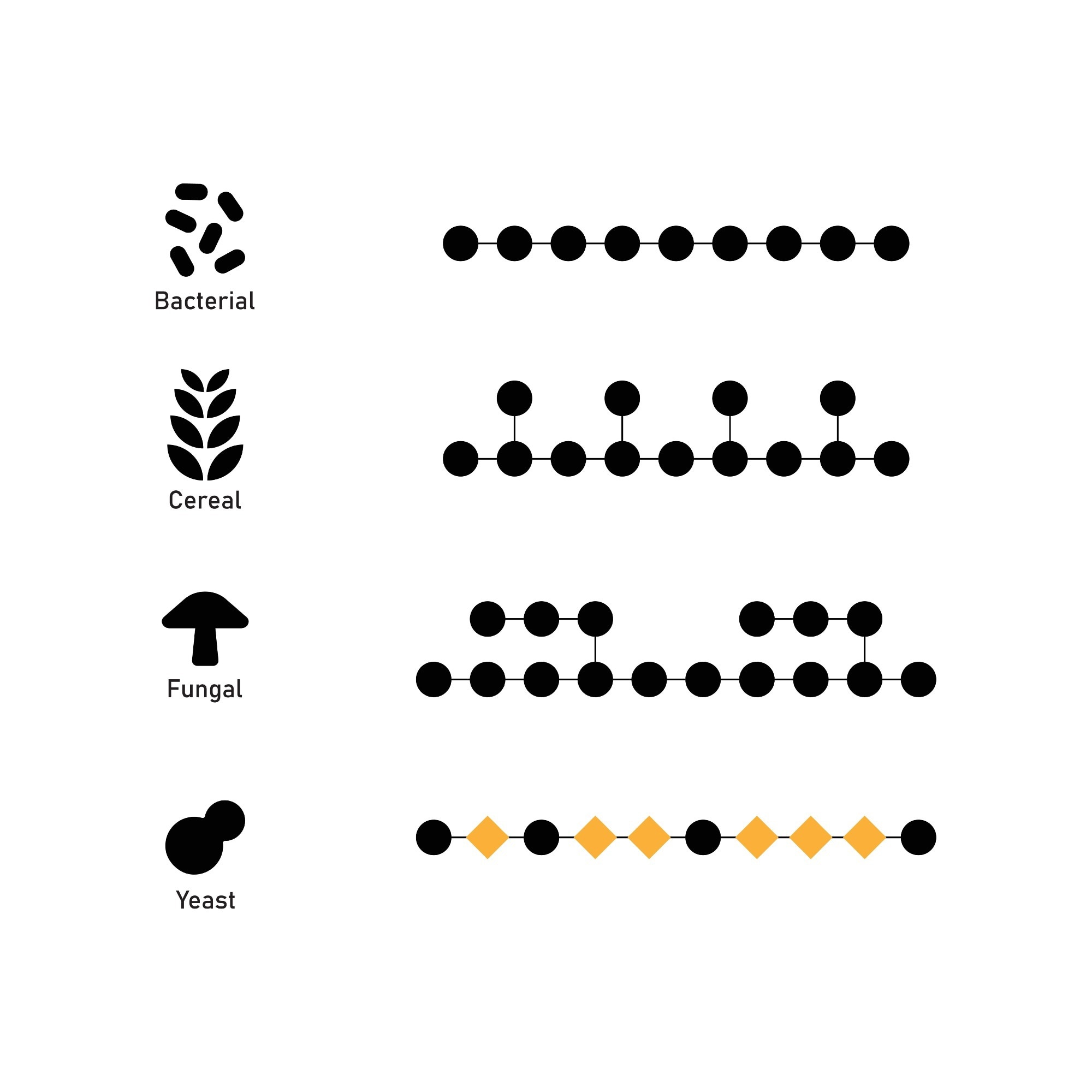

Beta-glucans are glucose polymers found in cereal grains and fungal cell walls. Cereal β-glucans contain β-1,3 and β-1,4 linkages, while fungal β-glucans typically consist of a β-1,3 backbone with β-1,6 branching structures.4,5

Recognition of fungal β-glucans occurs primarily via Dectin-1, with particulate, higher-molecular-weight yeast β-glucans inducing stronger receptor clustering and signaling compared to more soluble mushroom-derived preparations. Differences in branching density, solubility, and molecular weight influence Dectin-1 isoform engagement and downstream NF-κB activation.5

Image Credit: Kooto / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Kooto / Shutterstock.com

Cereal β-glucans and immune training

Oat-derived β-glucans enhance TNF-α and IL-6 production upon secondary TLR stimulation in monocytes and macrophages. These effects are associated with upregulation of glycolytic enzymes and TCA cycle intermediates, and are attenuated by pharmacologic inhibition of glycolysis or TCA activity.4

These findings derive predominantly from murine bone marrow–derived cells and THP-1 models and therefore represent mechanistic evidence rather than direct population-level clinical outcomes.4

Mushroom β-glucans and innate immune reprogramming

β-Glucans from Agaricus bisporus induce trained immunity, although generally less potently than purified yeast-derived whole glucan particles5. Enhanced cytokine responses are particularly notable following TLR2 stimulation.5

The magnitude of cytokine enhancement is modest (approximately 1.5–2-fold relative to untrained controls) and more variable than purified yeast β-glucan preparations.5

In vivo administration in mice shifts bone marrow hematopoiesis toward myeloid-committed progenitors and generates macrophages with enhanced secondary responsiveness. These findings support central (HSPC-level) as well as peripheral innate immune training, though translation to long-term human dietary intake remains to be demonstrated.5

Dietary patterns and immune regulation

Western-style diets and maladaptive immune training

High-fat Western diets induce NLRP3-dependent innate immune reprogramming and persistent inflammatory imprinting. Some metabolic-diet–induced states may differ mechanistically from canonical β-glucan–induced trained immunity, highlighting heterogeneity within innate immune memory programs.2

Plant-forward and fiber-rich diets

Short-chain fatty acids influence histone acetylation and inflammatory gene expression. However, robust evidence linking whole-diet patterns to durable trained immunity phenotypes in humans remains limited2,3.

Image Credit: Marcus Z-pics / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Marcus Z-pics / Shutterstock.com

Practical, evidence-aligned takeaways

Experimental studies demonstrate that β-glucans induce epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming in innate immune cells.1,2,4,5 At present, dietary modulation of trained immunity should be regarded as a biologically plausible mechanistic framework rather than a clinically validated immune-enhancing intervention.2–5

Beta Glucan and the Immune System

Important considerations

Most evidence derives from in vitro systems or animal models.2–5 Well-controlled, long-term human intervention studies are required to clarify causality, dose–response relationships, safety parameters, and clinical relevance.2,3

References

- Netea, M.G., Joosten, L. A., Latz, E., et al. (2016). Trained immunity: a program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 352(6284). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf1098. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaf1098

- Netea, M. G., Domínguez-Andrés, J., Barreiro, L. B., et al. (2020). Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 20(6); 375-388. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-020-0285-6. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41577-020-0285-6

- Cortes-Perez, N. G., de Moreno de LeBlanc, A., Gomez-Gutierrez, J. G., et al. (2021). Probiotics and Trained Immunity. Biomolecules 11(10). DOI: 10.3390/biom11101402. https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/11/10/1402

- Pan, W., Hao, S., Zheng, M., et al. (2020). Oat-derived β-glucans induced trained immunity through metabolic reprogramming. Inflammation 43(4); 1323-1336. DOI: 10.1007/s10753-020-01211-2. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10753-020-01211-2

- Case, S., O’Brien, T., Ledwith, A. E., et al. (2024). β-glucans from Agaricus bisporus mushroom products drive Trained Immunity. Frontiers in Nutrition 11. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1346706. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1346706/full

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 15, 2026