Introduction

Enzyme activation: The key to better nutrient absorption

Gut health, glucose response, and inflammation

Common sprouted foods

Safety and preparation

Cooked vs. raw sprouts

Conclusions

References

Further reading

How a simple germination step transforms grains into enzyme-powered foods that nourish the gut, steady blood sugar, and unlock hidden nutrition.

Image Credit: Daniel_Dash / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Daniel_Dash / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

This article discusses the biological mechanisms by which sprouting grains prior to their consumption improves the nutritional quality of these foods while simultaneously conferring digestive and metabolic health benefits through enzyme-mediated remodeling of macronutrients and antinutrients during early germination.1

Enzyme activation: The key to better nutrient absorption

During early germination, water uptake activates metabolic pathways that stimulate the production of hydrolytic enzymes like α- and β-amylase, proteases, lipase, and phytase. These endogenous enzymes progressively degrade antinutrients such as tannins, phytic acid, lectins, α-galactosides, and protease inhibitors, thereby improving the bioavailability of crucial macromolecules in a species- and time-dependent manner.2

Sprouting increases the availability of amino acids like lysine, leucine, valine, and threonine, as proteases solubilize storage proteins in sprouts. Reduced phytate and tannins also limit mineral chelation, thereby increasing the bioaccessibility (rather than absolute concentration) of calcium, iron, and zinc across legumes and cereals after approximately 24–72 hours of germination.2

B-vitamins such as thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxine, and folate also become more nutritionally accessible as germination enhances enzymatic release from bound forms and improves utilization efficiency. Cell-wall-modifying enzymes such as esterases and β-glucanases act on non-starch polysaccharides and β-glucans to alter the fiber matrix and increase the extractable, fermentable fractions, thereby improving fiber solubility and functionality in sprouted grains, depending on grain type and germination duration.2

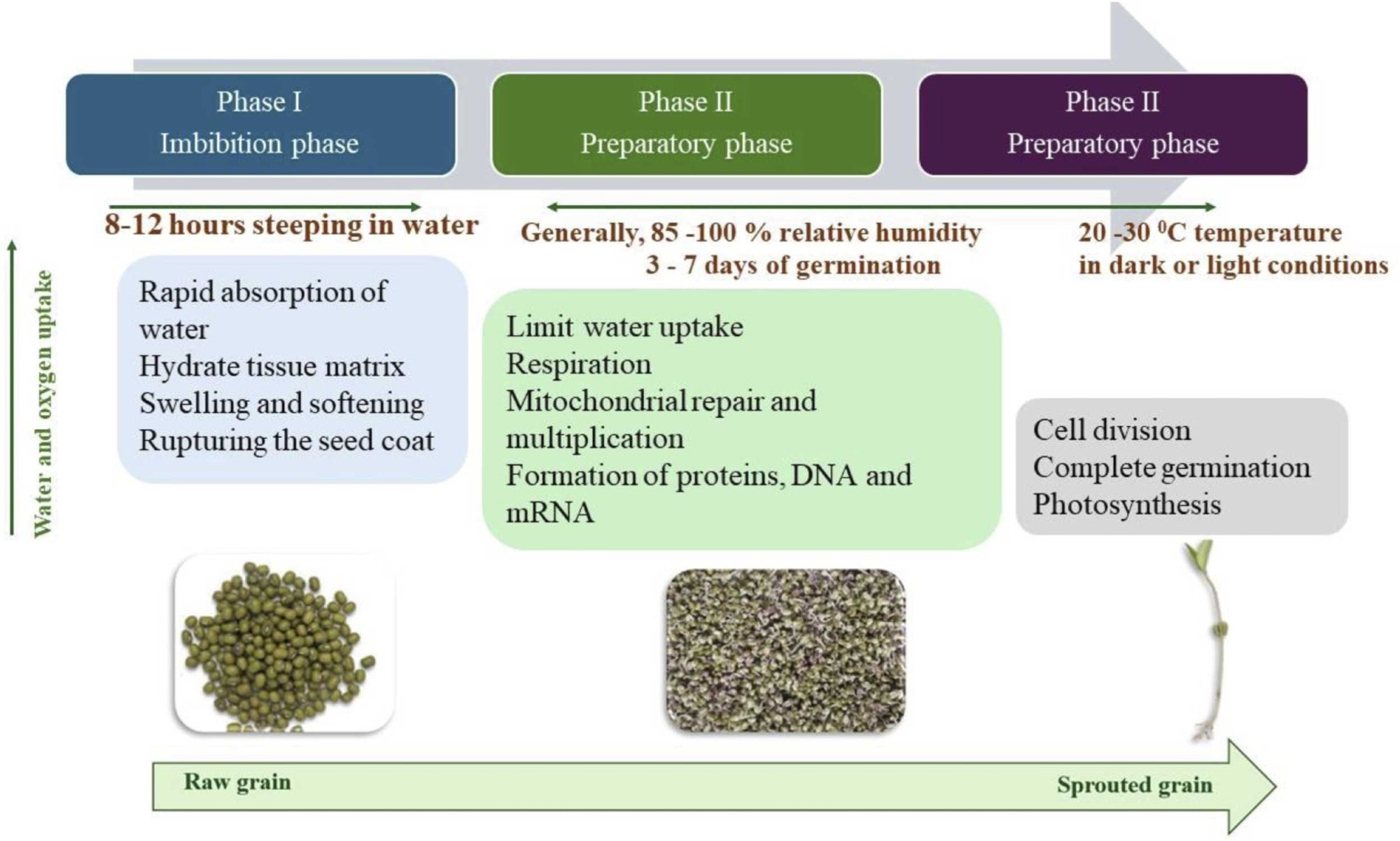

Typical germination process.

Gut health, glucose response, and inflammation

Enzyme-rich germination increases polyphenols and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels while enhancing the activity of naturally occurring α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors. By reducing the rate of carbohydrate digestion and post-meal glucose excursions, sprouting supports insulin signaling and overall glycemic control. For example, germinated brown rice intake improves fasting glucose levels and enhances short-chain fatty acid signaling in both animal models and human interventions.1,3

Consuming sprouted grains reduces antinutrients such as phytic acid and lectins and degrades indigestible oligosaccharides that often contribute to digestive distress. Together, these changes can reduce bloating and improve nutrient absorption. The breakdown of macronutrients and antinutritional factors during germination enhances bioavailability and palatability, further supporting smoother digestion in everyday foods.1,3

Germinated grains also modulate gut microbial composition, strengthen intestinal barrier integrity, and increase short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, which promotes metabolic homeostasis and insulin sensitivity along the gut–liver axis. In particular, germinated brown rice has been associated with probiotic shifts and reduced low-grade inflammation.1,3

Image Credit: Jiri Hara / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Jiri Hara / Shutterstock.com

Common sprouted foods

In cereals like sprouted wheat and millet, germination activates amylases and proteases that convert starch to simple sugars, as well as proteins to peptides and free amino acids, thereby improving digestibility and flavor. Phytase activity during sprouting also reduces phytic acid, further enhancing mineral bioavailability without compromising whole-grain integrity.

Protein digestibility is significantly enriched after three to five days of sprouting at moderate temperatures, while overall protein quality improves through increased essential amino acid availability. Quinoa sprouts are particularly rich in total phenolics and flavonoids that contribute to elevated antioxidant capacity.1,4

Sprouted lentils, chickpeas, and mung beans provide more vitamin C and free amino acids, alongside reduced oligosaccharides and enzyme inhibitors, with mung bean sprouts widely valued for their biological functions across Asian cuisines. Sprouted alfalfa and sunflower seeds are other convenient sources of proteins, vitamins, and polyphenols.

Together, these sprouted grains, pulses, and seeds provide versatile, nutrient-dense options that are easily integrated into breads, beverages, salads, and cooked dishes, while contributing antioxidants, improved macronutrient bioavailability, and better sensory properties.1,4

Safety and preparation

Importantly, sprouts are at a greater risk of contamination that can begin at the seed and persist through soaking, germination, handling, and storage. Therefore, consumers are advised to use untreated seeds specifically meant for sprouting, rather than pesticide-treated seeds. An aerobic, well-ventilated location during germination is also crucial for limiting microbial growth.

Various sanitation interventions are available, including chemical methods such as 50–200 parts per million (ppm) chlorine washes or chlorine dioxide gas, which penetrates biofilms more effectively than aqueous chlorine. Organic acid treatment, such as 2.5% lactic acid with mild heat, has been shown to reduce the proliferation of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Electrolyzed water, ozone, and ultraviolet-C (UV-C) have also been reported as effective supplementary interventions.1,5

Low temperatures of 4–5 °C, when combined with modified-atmosphere packaging, limit spoilage; however, these temperatures vary based on the specific grain species. Optimizing wash chemistry and thorough drying before packing further suppresses microorganism growth during storage.1,5

Image Credit: AnaMarques / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: AnaMarques / Shutterstock.com

Cooked vs. raw sprouts

Germination increases polyphenols, flavonoids, and overall antioxidant capacity, which are best preserved in minimally processed and fresh applications like salads or toppings. However, cooked formats are preferred when texture, shelf life, and product performance are prioritized.

Sprouted flours enhance sensory qualities in breads and cookies while improving spread and moisture retention in baked goods. Heat-moisture and hydrothermal treatments modify the structure and functional properties of starch in sprouted grains, thereby improving texture, firmness, and stability, which are often desired when preparing noodles and other stable grain foods.1,2

Conclusions

Early germination activates amylases, proteases, lipases, and phytases that convert starch into simple sugars, proteins into amino acids, and phytate into absorbable mineral forms. In addition to reducing the activity of antinutrients, consuming sprouted grains increases the levels of polyphenols and GABA, while enhancing the bioavailability of calcium, iron, zinc, and various vitamins through enzyme-driven matrix modification.1–3

References

- Ikram, A., Saeed, F., Afzaal, M., et al. (2021). Nutritional and end‐use perspectives of sprouted grains: A comprehensive review. Food Science & Nutrition 9(8); 4617-4628. DOI: 10.1002/fsn3.2408. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/fsn3.2408

- Gunathunga, C., Senanayake, S., Jayasinghe, M. A., et al. (2024). Germination effects on nutritional quality: A comprehensive review of selected cereals and pulses changes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 128. DOI: 10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889157524000589

- Sun, Y., Li, C., & Lee, A. (2025). Sprouted grains as a source of bioactive compounds for modulating insulin resistance. Applied Sciences 15(15). DOI: 10.3390/app15158574. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/15/15/8574.

- Waliat, S., Arshad, M. S., Hanif, H., et al. (2023). A review on bioactive compounds in sprouts: extraction techniques, food application and health functionality. International Journal of Food Properties 26(1); 647-665. DOI: 10.1080/10942912.2023.2176001. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10942912.2023.2176001#abstract

- Benincasa, P., Falcinelli, B., Lutts, S., et al. (2019). Sprouted Grains: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 11(2). DOI: 10.3390/nu11020421. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/2/421

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 5, 2026