Introduction

Heat as a stress signal

The heat shock response

Heat stress and cellular damage beyond HSPs

Heat stress effects on gene expression and stress networks

Acute vs. chronic heat exposure

Clinical and public health relevance

Emerging questions and research frontiers

References

Further reading

Rising temperatures disrupt human cellular stability by impairing proteostasis, altering mitochondrial function, reprogramming gene expression, and reshaping immune responses, ultimately shifting cells from adaptive survival toward inflammation and programmed death under sustained stress.

Image Credit: Duangdaw / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Duangdaw / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Rising temperatures, whether from extreme heat waves or prolonged exposure in workplaces, strain human health. Prolonged heat stress adversely affects cellular function, increasing the risk of acute illnesses and worsening pre-existing cardiac or respiratory disorders. Higher temperatures destabilize protein structures, damage cell membranes, and disrupt energy metabolism, leading to the accumulation of damaged proteins.

Heat-induced molecular stress underlies many heat-related health outcomes observed in exposed populations.3 This article explains how continuous exposure to rising temperatures disturbs cellular functions ranging from protein damage and mitochondrial stress to gene expression changes, immune effects, and long-term health risks.

Heat as a stress signal

Maintaining optimal cellular temperature ensures the stability of proteins and other molecules. Conversely, increased exposure to heat renders noncovalent interactions that stabilize biomolecules (e.g., hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions) less favorable, alters the redox balance, and reduces protein stability by promoting unfolding or forming unstable structures.13

As molecular motion within cells increases following heat exposure, cellular membranes become more fluid, which reduces membrane barrier function and the organization of signaling complexes. Intracellular signaling processes are also affected, as proteins involved in these reactions can misfold or dissociate from binding partners, potentially interfering with pathways governing growth, stress, and survival.23

Cells also detect heat through thermosensitive ion channels (thermo-TRPs), including TRPV1 (activated by noxious heat, typically >43°C), which can shape downstream inflammatory and pain-related signaling.3

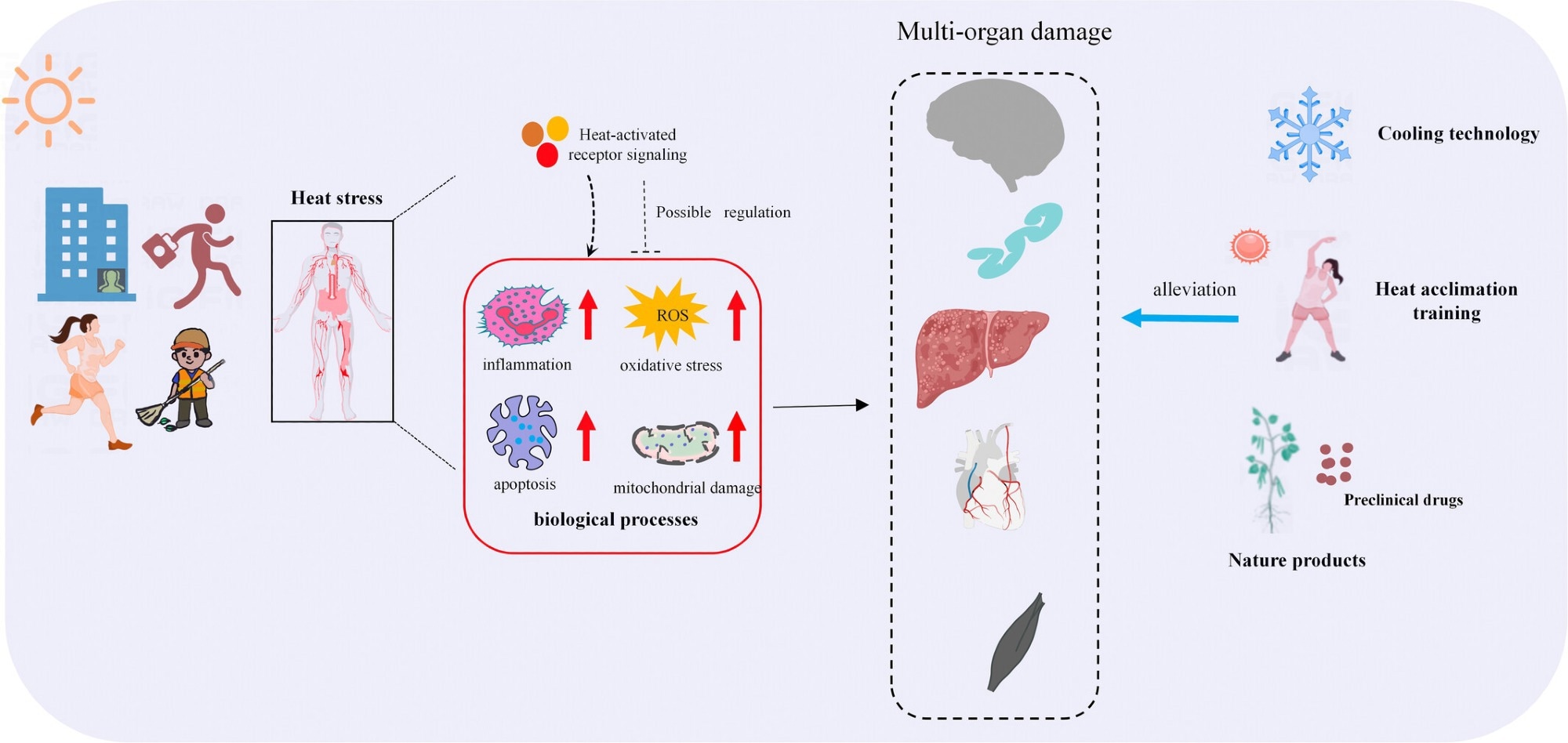

Thermal environment-mediated pathophysiologic processes in the body and their coping strategies. Working or exercising in extreme heat environments can lead to heat stress in the organism. Heat stress can induce inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and mitochondrial damage in the body by activating heat-sensitive signaling pathways, leading to multi-organ injuries such as central nervous system injury, intestinal dysfunction, liver injury, cardiovascular system injury, and skeletal muscle injury. Current coping strategies for heat stress injury include cooling techniques, heat acclimatization training, and the use of preclinical medications and natural products, and these coping strategies can mitigate a range of pathological processes induced by heat stress, thereby reducing multi-organ damage.3

The heat shock response

Introduction to heat shock proteins (HSPs)

HSPs are proteins produced by the cell during stress that act as a ‘chaperone’ for other proteins. HSPs temporarily bind to unfolded or altered protein structures, thereby allowing damaged proteins to regain their form or transition to degradation. This protective system is activated within a short period after a rise in temperature and is found in microbes and humans, underscoring its essential role in cell survival.1

Major HSP families induced during heat shock include HSP100/110, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and small HSPs, which collectively support proteostasis by refolding proteins or routing irreversibly damaged proteins toward degradation.1

Regulation of the heat shock response

The heat shock response is tightly regulated by heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), a transcription factor that monitors protein quality within the cell. HSF1 remains inactive until stress exposure activates it, promoting HSF1 trimerization and nuclear translocation.

After entering the nucleus, HSF1 trimers bind with specific deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences to activate genes that produce HSPs. Increased HSP concentration is essential for restoring protein structure and protecting cellular function from heat shock.1

HSF1 activity is also controlled by feedback: chaperones such as HSP70 and HSP90 can restrain HSF1 under non-stress conditions and contribute to attenuation of the response as proteostasis is restored.1 In addition, HSF1 function is fine-tuned by post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and SUMOylation, while deacetylation by NAD+-dependent SIRT1 can attenuate transcriptional activity, thereby linking metabolic state to heat shock gene regulation.1

Image Credit: Julien Tromeaur / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Julien Tromeaur / Shutterstock.com

Heat stress and cellular damage beyond HSPs

Proteostasis disruption

When cells are exposed to continuous or intense heat, proteins undergo structural alterations faster than the cells can recover, thereby exceeding the capacity of chaperones and degradation pathways. The subsequent accumulation of damaged proteins exhausts the cell’s recovery process.

To overcome these effects, cells activate stress responses that reduce protein synthesis rates and reorient metabolic functions toward repair and recovery. Consistent with this reprioritization, heat stress can suppress growth- and proliferation-related programs while increasing investment in protein quality control and damage mitigation. Importantly, if the imbalance persists, stress signals initiate cellular dysfunction and, ultimately, programmed cell death.2,4

Mitochondrial stress and cell fate

Heat exposure negatively affects mitochondria by interfering with temperature-sensitive energy-producing and chemical-balancing processes within this organelle. Higher temperature can impair mitochondrial function, which increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can damage important mitochondrial components like proteins, fats, and DNA.3

Heat stress can also activate NADPH oxidase (including NOX1 via ERK signaling), increasing the NADP+/NADPH ratio and further amplifying ROS production beyond mitochondrial sources.3

Heat also causes cells to use less efficient energy methods in an effort to preserve adenosine triphosphate (ATP) reserves. When mitochondrial damage persists, calcium imbalance and oxidative stress increase the cell death signals like cytochrome c, which causes cells to shift from adapting stress responses to activating programmed cell death pathways.2,3

In this context, cytochrome c release promotes apoptosome formation and caspase-9 activation, which, in turn, activate executioner caspases such as caspase-3, thereby illustrating the caspase-dependent nature of many heat-associated apoptotic responses.2

Autophagy (including mitophagy) is often induced alongside these mitochondrial stresses and can be protective by removing damaged organelles, although its relationship to cell death depends on context and stress severity.2,3

Heat stress effects on gene expression and stress networks

When cells are exposed to extreme heat, numerous genes involved in cellular protection, protein quality control, and metabolism become activated, whereas the genes that control cell growth are suppressed. This coordinated genetic reprogramming allows cells to redirect stored energy from supporting growth to activating survival mechanisms.4

In a controlled human model of passive exposure to extreme environmental heat (sauna), peripheral blood mononuclear cells showed rapid transcriptome changes even without a large rise in core temperature, and these changes continued to amplify one hour into recovery; the overall response was predominantly inhibitory, with more than two-thirds of differentially expressed genes being downregulated.4

Notably, exposure time and modest changes in core temperature did not significantly influence the transcriptomic pattern, suggesting that cellular heat sensing and stress signaling can occur even before overt hyperthermia develops.4

In that same model, differentially expressed genes mapped to stress-associated pathways, including proteostasis, altered protein synthesis, energy metabolism, cell growth/proliferation, and cell death/survival, with signatures consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction.4

Several studies in humans exposed to heat stress have reported reduced gene expression of genes involved in antigen presentation and adaptive immune signaling, along with altered activity in inflammation-related pathways. In the sauna exposure study, immune-related gene expression was reduced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, supporting the idea that heat can transiently reprogram immune functions during and after exposure.4 Simultaneously, stress-responsive signaling cascades interact with immune regulators like nuclear factor kappa B and cytokine-associated networks to reshape immune functions and modify inflammatory signaling.2,3

Acute vs. chronic heat exposure

Short-term heat exposure can lead to heat stroke when the body's temperature regulation fails, resulting in cell damage and inflammation within hours. During this period, homeostasis is disrupted by endothelial injury, increased cell membrane permeability, as well as ion imbalance.3 Severe heat illness can also involve systemic inflammatory responses and downstream organ dysfunction.3

In severe cases, endothelial dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities, and systemic inflammatory activation can converge to promote multi-organ injury.3

Comparatively, chronic exposure to high temperatures leads to continuous intracellular stress that shifts energy consumption towards repair, rather than for growth and development. This repeated process triggers stress responses and reduces cellular efficiency, thereby limiting tissues' capacity to overcome exposure to other forms of stress.2,3

How does extreme heat affect your body? - Carolyn Beans

Clinical and public health relevance

Heat stroke, which results from excessive body overheating, can damage the liver, heart, and brain and can also cause inflammation and abnormal coagulation. The most vulnerable population for heat stroke includes older people, people with existing heart issues, and laborers working in extreme temperatures.3

Beyond the immediate effects of heat, regular exposure to heat stress can accelerate cell aging, damage organs, and increase the risk of chronic diseases. As a result, heat stress is considered a public health issue, rather than just an environmental challenge.3

Emerging questions and research frontiers

The capacity of cells to withstand heat is determined by variations in basic protein maintenance, mitochondrial function, and their genetic responses. Human in vivo data also indicate that heat can trigger broad suppression as well as activation of stress programs, with substantial inter-individual variability in transcriptional responses under a standardized exposure.4

Age and metabolic health often determine cellular resistance to heat, as older or weaker cells have continuous suppression of energy production and immunity. Mechanistically, the balance between adaptive stress programs (e.g., HSP induction and autophagy) and cell-death programs (apoptosis, necrosis, and other regulated death pathways) is strongly shaped by stress intensity and duration.2,3 Recent research shows that certain genes that contribute to protein stability, mitochondrial production, and stress signaling can be associated with the heat-coping capacity of cells. Thus, identifying these molecular fingerprints may clarify why some individuals recover quickly from heat exposure, whereas others sustain severe injury.4

References

- Singh, M. K., Shin, Y., Ju, S., et al. (2024). Heat Shock Response and Heat Shock Proteins: Current Understanding and Future Opportunities in Human Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25(8). DOI: 10.3390/ijms25084209. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/8/4209

- Fulda, S., Gorman, A. M., Hori, O., & Samali, A. (2010). Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. International Journal of Cell Biology. DOI: 10.1155/2010/214074. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2010/214074

- Ding, X., & Gao, B. (2025). Heat Stress‐Mediated Multi‐Organ Injury: Pathophysiology and Treatment Strategies. Comprehensive Physiology 15(3). DOI: 10.1002/cph4.70012. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cph4.70012

- Bouchama, A., Aziz, M. A., Mahri, S. A., et al. (2017). A model of exposure to extreme environmental heat uncovers the human transcriptome to heat stress. Scientific reports. 7(1). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-09819-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-09819-5

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 16, 2026