Infections caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant are common among individuals who have recovered from prior infection or have been vaccinated against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The Omicron has quickly overtaken the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant as the dominant circulating strain globally. Currently, the original Omicron strain is being replaced by its newer sub-lineages BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, and BA.5. Despite its high infectivity, few studies have documented serial Omicron infectivity.

Study: Serial Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Following Three-dose COVID-19 Vaccination. Image Credit: Najmi Arif / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

In a new study published on the medRxiv* preprint server, scientists studied SARS-CoV-2 humoral responses in a healthy young person who was infected by the Omicron BA.1.15 variant ten weeks after receiving a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. This individual was subsequently reinfected with the BA.2 strain thirteen weeks later. The responses of this individual were compared to those of 124 COVID-19 naive vaccine recipients.

Background

In British Columbia (BC), Canada, the COVID-19 vaccine coverage is relatively high, with high-risk individuals who are currently eligible for a fourth dose of the vaccine. Despite the impressive vaccine coverage, BC has recently experienced BA.1- and BA.2-driven fifth and sixth COVID-19 waves, respectively.

Prior research has examined post-vaccination Omicron infections and reinfections after exposure to previous variants. However, only one study analyzed the serial Omicron infection incidence through viral genomic surveillance, while vaccine- and infection-induced immune responses after serial Omicron infections are still unexplored.

About the study

In the current study, researchers longitudinally characterized humoral responses in a healthy young person who was infected by the Omicron BA.1.15 variant ten weeks after a third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine and subsequently reinfected with BA.2 thirteen weeks later. These responses were compared to 124 COVID-19-naive vaccinees over the same period.

Based on the results and a literature review, the researchers concluded that vaccination provides only limited protection against infection and/or reinfection by the Omicron variant.

Study findings

The risk of repeated infection with Omicron subvariants may be higher than currently assumed from available data on reinfection rates. The researchers noted that the study participant was a frontline healthcare worker, which may have augmented their vulnerability to exposure and reinfection as compared to the general population.

Case participant history and longitudinal humoral responses against wild-type and Omicron BA.1 SARS-CoV-2. Panel A: Case participant timeline. Immunizations and SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection history are shown at the top. Longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 anti-N serology results are shown in small green (anti-N negative) or orange (anti-N positive) circles. Large black circles denote time points where additional humoral functions, shown in panels below, were measured. Panel B: Longitudinal anti-S-RBD IgG log10 concentrations in case participant (large circles) versus the comparison group of SARS-CoV-2-naive individuals (small circles) at various time points following two- and three-dose COVID-19 vaccination. Wild-type (WT) specific anti-S-RBD responses are shown in red; Omicron BA.1-specific ones are shown in blue. Matching solid lines connect the participant’s longitudinal values, while dotted lines connect the median values for the comparison group. Approximate times of BA.1 and BA.2 infections are shown with arrows. Total Ns (including the case participant) are shown at the bottom of the plot. Later time points have smaller Ns because some control participants were censored due to post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection or had not yet completed the visit. Panel C: same as previous, but for longitudinal ACE2% displacement function from wild-type (red) and BA.1 (blue) S-RBDs. Panel D: same as previous, but for longitudinal live virus neutralization function against wild-type (red) and BA.1 (blue) strains. ULOQ/LLOQ: upper/lower limit of quantification.

It should be noted that the findings from this individual should not be generalized. As a result, the researchers compared the vaccine-induced immunoglobulin G (IgG), angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor competition, and virus neutralization responses of the study participant with the median values observed in diverse controls who were vaccinated during the same time period.

The high rate of community transmission in many regions during recent Omicron-driven pandemic waves is consistent with the finding that three-dose vaccination failed to protect against Omicron BA.1 infection. The risk of infection is expected to be higher among individuals who have received fewer than three doses of the vaccine.

Thus, currently available vaccines, which are based on the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 sequence, will not provide full protection against Omicron strains, as they have evolved to evade immune responses. However, research has shown that hybrid immunity, which is immunity derived from a combination of infection and vaccination, is highly effective in protecting against infection with SARS CoV-2 variants.

In this regard, the researchers of the current study showed that symptomatic BA.1 infection boosted vaccine-induced humoral responses against both BA.1 and BA.2 in the study participant. However, a subsequent symptomatic infection by BA.2 could not be prevented.

The participant’s ACE2 competition and virus neutralization responses against BA.1 appeared to plateau, even after vaccination and two Omicron infections. The level at which the response was observed was significantly lower than those seen against the wild-type strain. This suggested that the participant will remain at risk of new infections with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.

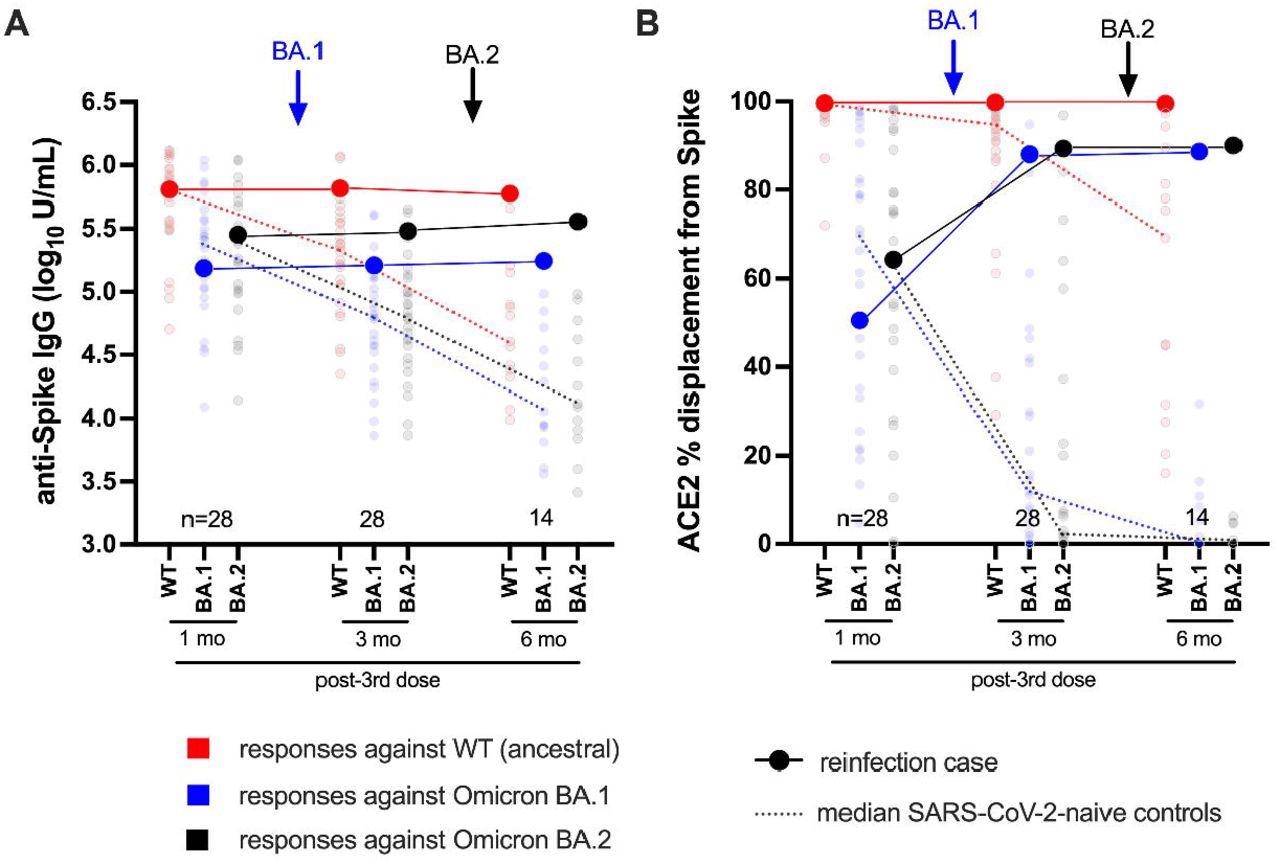

Longitudinal humoral responses against wild-type, BA.1 and BA.2 Spike antigens. Panel A: Anti-Spike IgG log10 concentrations in case participant (large circles) versus the subset of the comparison group of SARS-CoV-2-naive individuals (small circles) at one, three and six months following three-dose COVID-19 vaccination. Wild-type-specific (WT) anti-Spike responses are in red; BA.1-specific ones are in blue; BA.2-specific ones are in black. Matching solid lines connect the participant’s longitudinal values; dotted lines connect the median values for the comparison group. Approximate times of BA.1 and BA.2 infections are shown with arrows. Total Ns (including the case participant) are shown at the bottom of the plot; the final time point has a smaller N because some control participants were censored due to post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection or had not yet completed the visit. Panel B: same as previous, but for longitudinal ACE2% displacement function from wild-type (red), BA.1 (blue) and BA.2 (black) Spike protein.

Conclusions

A key limitation of the study is that T-cell responses were not analyzed. T-cell responses could reduce disease severity but may have a limited effect on viral transmission.

The researchers of the current study also indicated that they may be underestimating the protection that is conferred from infection and reinfection. In fact, the study participant did not require hospitalization after both infections, which suggests that vaccination was effective in its primary goal of preventing severe disease.

Taken together, the findings from the current study demonstrate the possibly limited ability of current COVID-19 vaccines to prevent serial infections and symptomatic disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Lapointe, R. H., Mwimanzi, F., Cheung, P. K., et al. (2022) Serial Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Following Three-dose COVID-19 Vaccination. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.05.19.22275026. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.19.22275026v1.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Lapointe, Hope R., Francis Mwimanzi, Peter K. Cheung, Yurou Sang, Fatima Yaseen, Rebecca Kalikawe, Sneha Datwani, et al. 2022. “Serial Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Following Three-Dose COVID-19 Vaccination.” Frontiers in Immunology 13 (September). https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.947021. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.947021.