Fermented foods are produced using microbes to enzymatically alter various food components, and the process not only preserves the food but also improves its nutritional value and taste. Fermented foods have been consumed worldwide and are also often linked to geographical regions and cultures. The recent popularization of fermented foods because of their health benefits has led to a wide range of readily available traditional and commercially produced fermented foods.

Advancements in sequencing technologies have made it possible to easily identify and characterize bacterial communities. Bacterial communities can vary in size, complexity, abundance, and function. Fermented foods are largely classified by the presence of lactic acid bacteria. Fermented foods from Asia, Africa, and Europe, including dairy products, kimchi, various types of kefirs, kombucha, and meat products, have been widely studied. However, fermented foods' microbial composition depends on the starting ingredients and microbial community, and the same foods might vary based on manufacturer, geographic location, and environmental factors.

Study Design and Methodology

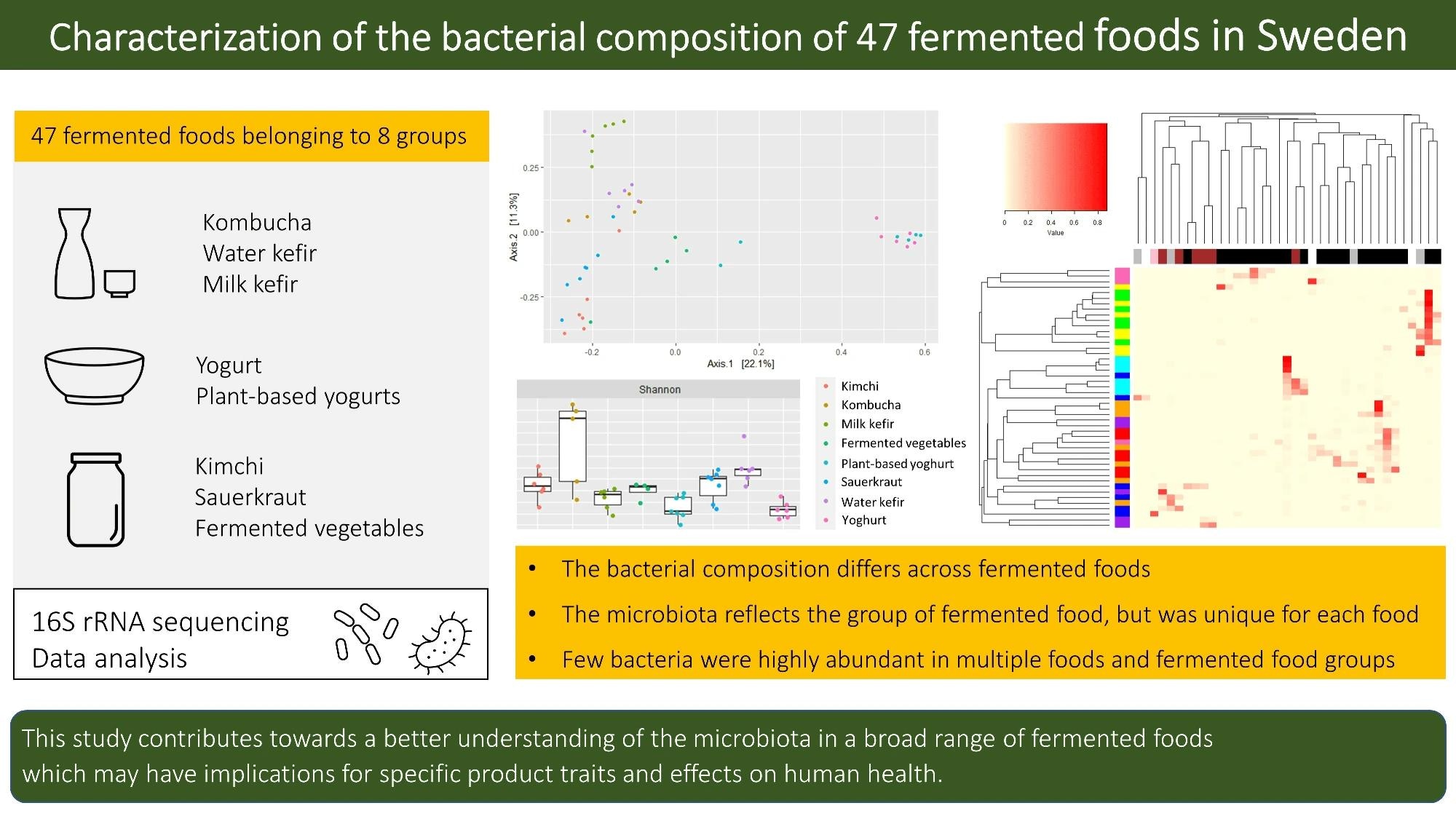

In the present study, the researchers investigated a wide range of commercial and homemade fermented foods locally available in Sweden. They covered eight major fermented group types, namely, tibicos or water kefir, kombucha, milk kefir, sauerkraut, plant-based yogurt, fermented vegetables, and kimchi.

Data Collection and Microbial Analysis

A total of 47 homemade and commercially available fermented foods were collected or prepared, and for foods for which the information was available, data on starter cultures and bacterial composition was obtained. The homemade fermented foods prepared by the authors included sauerkraut, kimchi, yogurt, kombucha, water kefirs, plant-based yogurt alternatives, and milk kefirs.

Statistical Approaches

For the microbial analysis, total deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to amplify the V3 and V4 regions of the 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (RNA) gene. Amplicon sequence variants were identified, and those classified as mitochondrial or chloroplast sequences were removed from the analysis.

National Center for Biotechnology's Nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used for the taxonomic assignment of the amplicon sequence variants, with reliable identification till the genus level. Additionally, the Inverted Simpson and Shannon diversity indices were calculated to determine the alpha diversity, and the richness was calculated after normalizing the amplicon sequence variant data.

The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was used to evaluate differences in richness and alpha diversity across the various fermented food groups, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for pairwise comparisons to determine if the differences in richness and alpha diversity were statistically significant. Furthermore, a principal coordinate analysis was conducted to assess the dissimilarities in bacterial composition. Relative abundances were used to estimate the proportion of lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria in each fermented and fermented food group.

Key Findings and Results

The results showed that a total of 2,497 amplicon sequence variants were retrieved and identified as belonging to 386 genera and 33 phyla. The richness and alpha diversity was found to vary significantly across various fermented foods and fermented food groups, indicating that the community structure of the bacteria present in these foods and those responsible for fermentation varied widely.

Diversity in Commercial and Homemade Products

Two homemade and one commercial kombucha and one commercially available water kefir were found to have the highest richness and Shannon diversity, while plant-based yogurt alternatives and fermented vegetables were found to have the lowest richness and diversity values. The kombucha and kefirs use a symbiotic bacterial and yeast culture, while the yogurts and fermented vegetables use a small and defined starter culture, which could explain the differences in richness and diversity.

Dominant Bacteria Across Fermented Foods

The bacterial composition was primarily dominated by lactic acid or acetic acid bacteria, and some bacteria were abundant across fermented food groups. Regular yogurt and plant-based yogurt alternatives had an abundance of Streptococcus thermophilus, while Lactiplantibacillus plantarum was found in large numbers in fermented cucumber, sauerkraut, and kimchi. Lactococcus lactis was found in one water kefir sample and most milk kefirs.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Conclusions and Future Research

Overall, the findings reported that fermented foods varied significantly in bacterial composition, richness, and abundance, with some foods such as kombucha and kefirs having very high richness and diversity values and plant-based yogurt alternatives and fermented vegetables having lower bacterial richness and diversity. The study highlights the need for further research to understand the differences in product traits based on microbial communities and the impact of these foods on human health.