A landmark study reveals that nearly a third of global antibiotic use ends up in rivers, threatening aquatic ecosystems and accelerating the rise of drug-resistant bacteria. This highlights the urgent need for global monitoring and mitigation strategies.

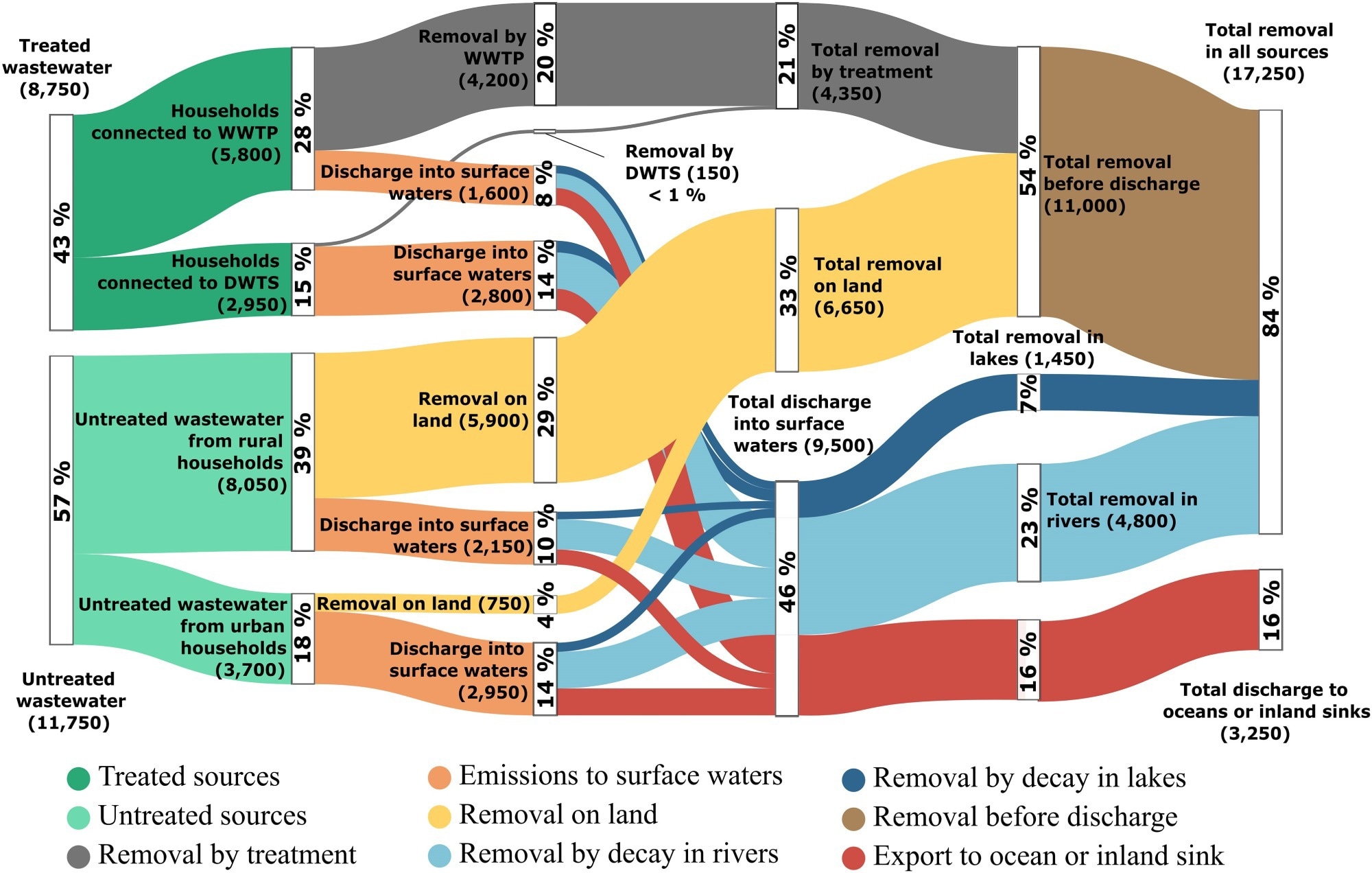

Contaminant pathways of antibiotics in the global aquatic environment. Modeled contaminant pathways and mass balances of antibiotics by path. Values in parentheses indicate total amounts of the top 40 antibiotics consumed worldwide in tonnes year−1; percentage values are relative to the total excretion amount (20,500 tonnes year−1).

Contaminant pathways of antibiotics in the global aquatic environment. Modeled contaminant pathways and mass balances of antibiotics by path. Values in parentheses indicate total amounts of the top 40 antibiotics consumed worldwide in tonnes year−1; percentage values are relative to the total excretion amount (20,500 tonnes year−1).

A McGill University-led study warns that millions of kilometres of rivers around the world are carrying antibiotic pollution at levels high enough to promote drug resistance and harm aquatic life.

Published in the journal PNAS Nexus, the study is the first to estimate the scale of global river contamination from human antibiotic use. Researchers calculated that about 8,500 tonnes of antibiotics—nearly one-third of what people consume annually—end up in river systems around the world each year, even after passing through wastewater systems in many cases.

"While the amounts of residues from individual antibiotics translate into only very small concentrations in most rivers, which makes them very difficult to detect, the chronic and cumulative environmental exposure to these substances can still pose a risk to human health and aquatic ecosystems," said Heloisa Ehalt Macedo, a postdoctoral fellow in geography at McGill and lead author of the study.

The research team used a global model validated by field data from nearly 900 river locations. They found that amoxicillin, the world's most-used antibiotic, is the most likely present at risky levels, especially in Southeast Asia, where rising use and limited wastewater treatment amplify the problem.

"This study is not intended to warn about the use of antibiotics – we need antibiotics for global health treatments – but our results indicate that there may be unintended effects on aquatic environments and antibiotic resistance, which calls for mitigation and management strategies to avoid or reduce their implications," said Bernhard Lehner, a professor in global hydrology in McGill's Department of Geography and co-author of the study.

The findings are especially notable because the study did not consider antibiotics from livestock or pharmaceutical factories, which are major contributors to environmental contamination.

"Our results show that antibiotic pollution in rivers arising from human consumption alone is a critical issue, which would likely be exacerbated by veterinarian or industry sources of related compounds," said Jim Nicell, an environmental engineering professor at McGill and co-author of the study. "Monitoring programs to detect antibiotic or other chemical contamination of waterways are therefore needed, especially in areas that our model predicts to be at risk."

Antibiotics in the global river system arising from human consumption, by Heloisa Ehalt Macedo, Bernhard Lehner, Jim Nicell, Usman Khan, and Eili Klein, was published in PNAS Nexus. This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, a James McGill Professorship, and a Fessenden Professorship in Science and Innovation award from McGill University.

Source:

Journal reference:

- Ehalt Macedo, H., Lehner, B., Nicell, J. A., Khan, U., & Klein, E. Y. (2025). Antibiotics in the global river system arising from human consumption. PNAS Nexus, 4(4). DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf096, https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/4/4/pgaf096/8113371