From fast nerve signals to microbial metabolites, scientists are uncovering the biological conversations between the gut and brain that may explain chronic pain, weight gain, and neurodegenerative disease, and point to a new generation of treatments that work by targeting communication rather than symptoms alone.

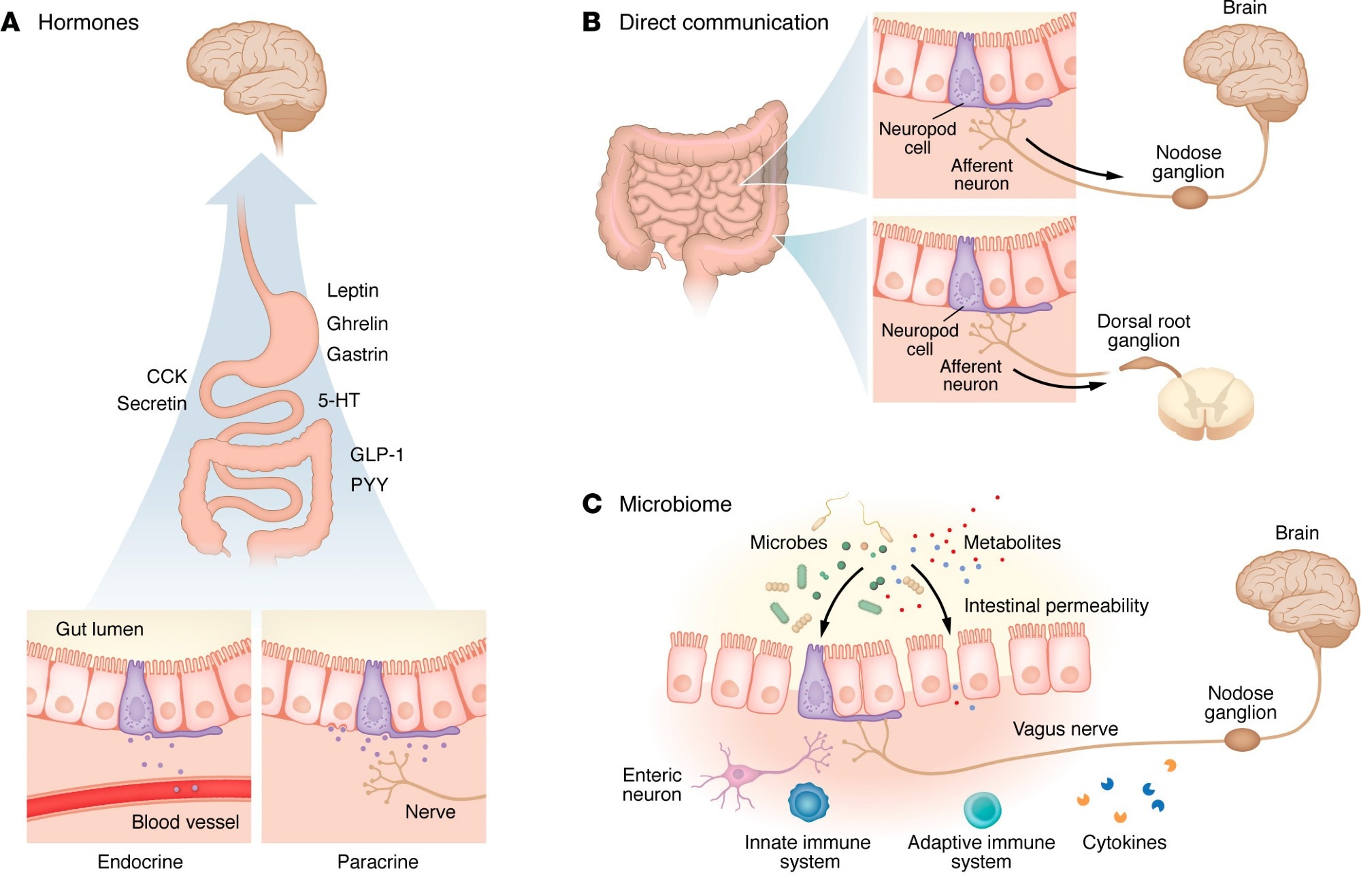

Mechanisms of signaling between the gut and the brain. Information can be transmitted from the gut lumen to the brain in a variety of ways, but recent research has highlighted four distinct categories of signaling. (A) In hormonal signaling, hormones from the gut epithelium are either released into the bloodstream (endocrine) or locally (paracrine), where they act via receptors to exert an effect. Hormones act on receptors in the ENS and CNS (particularly the hypothalamus) to receive these signals. 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin). (B) In neuropod-mediated signaling, EECs form close connections that rapidly transmit information from the gut lumen to the CNS. In more proximal regions of the gut (i.e., stomach, small intestine), signals are typically transmitted via the vagus nerve and convey nutritive information. Neuropod signaling in more distal regions (i.e., colon) conveys information related to visceral pain and stretch, which are received by the brain via the dorsal root ganglia. (C) Gut microbiota produce local effects in the gut lumen that affect epithelial permeability and allow transmission of the microbiota or associated metabolites into the bloodstream. Some of these changes induce an inflammatory response. Alternatively, microbes or metabolites (such as short-chain fatty acids) act locally on receptors to modify cell function. (D) The gastrointestinal immune system surveils the gut lumen with resident T cells and neutrophils that are activated by microbes and their metabolites and convey signals to the brain. Responses can be modified via inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract, leading to increased permeability and allowing further immune interactions. Concurrently, top-down mechanisms have been described, including glucocorticoid-dependent activation of ENS microglia leading to inflammation within the gut epithelium.

In a recent review published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers synthesized evidence from roughly 200 cited studies to elucidate the past decade of research on the “gut–brain axis.” The review delineates four distinct mechanisms of communication between these formerly thought-to-be distinct systems: hormonal signaling, direct neural connections, microbiome interactions, and immune system pathways.

Review findings highlight how dysfunction in any of these communication pathways may contribute to disorders ranging from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) to Parkinson’s disease (PD) and depression. Furthermore, it details how modern therapeutics leverage these pathways, demonstrating the clinical potential of targeting gut–brain communication.

Historical Foundations and Modern Scientific Advances

For more than 2,000 years, human academics have hypothesized a physiological link between the digestive system and the mind, a concept famously attributed to Hippocrates, who posited that “all diseases begin in the gut,” and William Beaumont, who observed that emotional states could visibly alter gastric function.

Unfortunately, despite substantial advancements in medical science and research, the specific mechanisms underlying these observations remained unknown until recently. Technological advancements in neuroimmunology, alongside a surge in interest in the microbiome, have catalysed advances in elucidating these mechanisms, particularly over the past decade.

The pace of scientific discovery, the complexity of gut–brain interactions, and widespread public misinformation have necessitated integrative reviews of the literature, revealing how, among other findings, novel classes of drugs (such as weight-loss–associated GLP-1 receptor agonists) engage these communication pathways to produce physiologically beneficial outcomes.

Scope and Methodological Approaches of the Review

The present review aims to address this need by synthesizing data from human and animal studies over the past 10 years to construct an updated mechanistic framework of gut–brain interaction, while also outlining key translational challenges.

The review included peer-reviewed publications across several interconnected research fields, including:

- Single-cell transcriptomics was used to identify 21 neuronal subtypes and three glial subtypes within the enteric nervous system (ENS).

- Retrograde tracing, a technique used to map neural pathways, reveals that specialized gut cells can connect to the brain in as few as a single synapse, although whether all such connections are true synapses remains debated.

- Chemogenetics (DREADDs), involving the use of “designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs” in mice to selectively silence or activate specific gut cells and observe changes in pain and anxiety.

- Clinical trial data, aggregating results from human studies involving GLP-1 receptor agonists and guanylyl cyclase C agonists.

Key Mechanisms of Gut–Brain Communication

The review reveals a profound, bidirectional association between gut physiology and neurobiology, highlighting the importance of the microbiome and metabolome in maintaining proper brain function, while emphasizing substantial inter-individual variability and the limits of causal inference. Key takeaways include:

Hormonal signaling: The gut has been identified as the body’s largest endocrine organ, secreting over 30 hormones, most of which exert physiological effects elsewhere. For example, while serotonin is a known neurotransmitter essential for brain health, research has found that over 90% of it is produced in the gut, where it primarily acts locally and does not cross the blood–brain barrier.

These studies have helped clarify mechanisms underlying obesity-related hormone dysregulation. While the hunger hormone ghrelin usually stimulates appetite, it is lower in individuals with obesity than in those with lower body mass indices (Body mass index">BMI), suggesting a state of hormonal resistance rather than hormonal excess.

Direct “neuropod” connections: Recent research has identified neuropod cells, specialized sensory epithelial cells that form direct synapse-like connections with the vagus nerve. These cells can distinguish between sugar (using the neurotransmitter glutamate) and artificial sweeteners (using ATP) in milliseconds, influencing food preferences and reward signaling at far faster timescales than classical endocrine pathways, although the anatomical generalizability of these connections remains under investigation.

The microbiome: The review details how specific microbial signatures correlate with neurological disease. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), misfolded alpha-synuclein proteins have been hypothesized to originate in the gut and travel to the brain via the vagus nerve. Animal studies have shown that severing the vagus nerve (vagotomy) can prevent gut-to-brain propagation of PD-like pathology; however, the directionality and universality of this pathway remain controversial, with evidence also supporting possible brain-to-gut spread.

Immune mediation: The review cites evidence that stress increases intestinal permeability through corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) signaling. In animal models, colonic inflammation has been shown to trigger immune cells, such as monocytes, to migrate to the brain, inducing anxiety-like behaviors, although the clinical implications of stress-related permeability are often overstated.

Encouragingly, the review also highlights modern clinical interventions such as linaclotide (for IBS) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (for obesity), which modulate gut–brain signaling pathways to reduce abdominal pain and promote weight loss, respectively, despite acting outside the primary symptomatic organ system.

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

The present review establishes the gut–brain axis not merely as an ancient hypothesis, but as a biologically grounded framework involving the multidirectional interplay of nerves, hormones, microbes, and immune cells. The findings suggest that neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease may, in some patients, be influenced by gastrointestinal processes, while digestive disorders such as IBS have demonstrable neural and central components.

While the review highlights ongoing challenges, particularly with reproducibility and patient-specific variability, continued research into psychobiotics and neurogastroenterological therapies may enable more targeted and effective treatments in the future.

Journal reference:

- Lorsch, Z. S., & Liddle, R. A. (2026). Mechanisms and clinical implications of gut-brain interactions. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 136(1). DOI – 10.1172/jci196346. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/196346