Children who consume the most low-calorie sweeteners aren’t cutting as much sugar as hoped, raising concerns that these “healthier” products may reinforce poorer dietary habits.

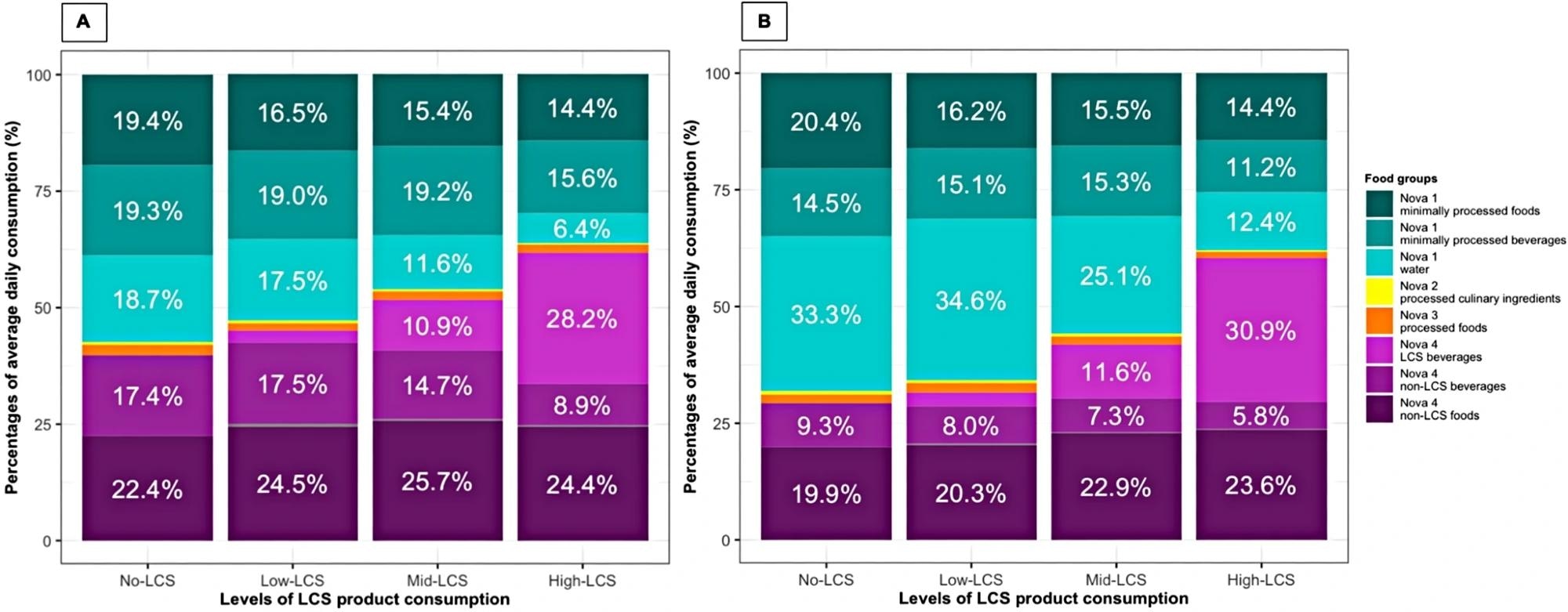

Grams of dietary intake by Nova subgroup in 2008–2009 (A) and 2018–2019 (B). A (N = 646). Percentages of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.4%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.3%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.6%; Nova 4 LCS beverages, 2.6; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.5%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.4%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.8%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.4%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.3%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.3%. B (N = 424). Percentages of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.6%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.0%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.1%; Nova 4 LCS beverages, 3.0; Nova 4 LCS food, 0.2%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.1%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.3%; Nova 3 processed foods, 1.3%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.1%

Grams of dietary intake by Nova subgroup in 2008–2009 (A) and 2018–2019 (B). A (N = 646). Percentages of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.4%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.3%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.6%; Nova 4 LCS beverages, 2.6; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.5%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.4%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.8%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.4%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.3%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.3%. B (N = 424). Percentages of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.6%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.0%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and beverages, 2.1%; Nova 4 LCS beverages, 3.0; Nova 4 LCS food, 0.2%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.1%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary ingredients, 0.3%; Nova 3 processed foods, 1.3%; Nova 4 LCS foods, 0.1%

A recent European Journal of Nutrition study examines the association between LCS product consumption and intakes of total energy, water, ultra-processed food and beverages (UPFB), and free sugars among UK children aged 4 to 18 years.

Excessive free sugar intake and health risks

Excessive free sugar intake is associated with an increased risk of cardiometabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular events. A previous study estimated that UK children consume approximately 12% of their total dietary energy intake from free sugars, which is almost twice the UK Government and World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of 5%.

In the UK, one in three children aged 10 to 11 years is of an unhealthy weight. To address this, increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has been a key point of intervention. To reduce obesity among children, several policies, including the Soft Drinks Industry Levy and the sugar reduction program, have been implemented to reduce the sugar content in foods and beverages. However, these strategies promoted LCS products that contain saccharin, sucralose, aspartame, acesulfame potassium, and steviol glycosides as lower-sugar alternatives.

Although randomized controlled trials have indicated short-term advantages of substituting sugar-sweetened beverages with LCS alternatives in obese adults regarding weight reduction, longitudinal observational studies have presented contradictory results. Longitudinal studies have associated LCS consumption with increased risk of cancer, obesity, adverse cardiometabolic outcomes, and mortality.

The underlying mechanism by which LCS consumption increases the risk of cardiometabolic disorders is poorly understood. Scientists have proposed that early-life exposure to LCS may have influenced the physiological processes of sweet-taste response, eating patterns, and appetite during growth and development. LCS could cause gut microbial dysbiosis and induce low-grade inflammation, leading to impaired glucose metabolism and an increased risk of obesity.

It is essential to understand how LCS product consumption affects overall dietary patterns, which include both ultra-processed and minimally processed foods. This information will help policymakers to focus on strategies to improve dietary quality and healthy weight in children.

About the study

The current study hypothesized that higher levels of LCS product consumption lead to the formation of less favorable dietary patterns, characterized by the inclusion of higher levels of ultra-processed foods and lower levels of minimally processed foods. To test the hypothesis, data were collected from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) between 2008 and 2019, a nationally representative dietary survey.

The current study categorized 140 items as LCS products, which were consumed by NDNS participants. For each participant, the daily concentration of LCS products consumed was estimated relative to the total amount of food and beverages consumed.

Participants were assigned to four groups based on their concentration of LCS product consumption, including No-LCS, Low-LCS (less than 6.8% g/d), Mid-LCS (between 6.9% and 17.4% g/d), and High-LCS groups (above 17.4% g/d).

Study findings

A total of 5,922 children were included in this study, with a median age of 10 years. Approximately 49.2% of the study cohort consisted of boys, 89.0% were of White ethnicity, and 64.9% had a normal body mass index (BMI). More than 36% of the participants belonged to the lowest household income tertile.

In comparison to other groups, children in the High-LCS group were younger and more likely to be of White ethnicity. Across survey years, the proportional distribution of children in each group, the LCS consumption characteristics, and the mean LCS intake have remained relatively unchanged in all study groups.

Between 2008 and 2009, 70.4% of participants had consumed LCS products, with a mean daily intake of 256.5 g. No significant change in prevalence and mean intake of LCS products was observed across the study period. Interestingly, between 2008 and 2009, a gradient of lower water intake was observed with increasing levels of LCS consumption.

In comparison to non-LCS product consumers, higher LCS product users tended to have lower intake of water, non-LCS ultra-processed beverages, and minimally processed beverages. While high LCS consumers initially had lower free sugar intake, this difference was no longer statistically significant by the end of the study period, showing a trend convergence over time.

The total energy intake for the Low-LCS and High-LCS groups showed a decline, with incremental yearly reductions of 14.8 kcal/day and 12.3 kcal/day, respectively, compared with the No-LCS group. Therefore, compared to non-LCS product users, a decline in total energy intake was observed among the highest consumers of LCS products.

Interestingly, all LCS consumption groups exhibited a declining trend in UPFB consumption over the study period. However, this positive trend was less pronounced in the High-LCS group. Similarly, the increase in minimally processed food and water intake over the 11 years was slowest in the High-LCS group, indicating a persistent and widening relative gap in dietary quality.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated that higher LCS product consumption was not consistently associated with lower free sugar intake in children, as the initial benefit disappeared over time. Furthermore, the findings showed that while all children’s diets improved in some ways, the improvements were slowest for children consuming the most LCS products. This indicates that these products may be part of a broader, less healthy dietary pattern and that their promotion represents a potential missed opportunity to encourage greater water consumption. In the future, more comprehensive research is needed to understand current dietary patterns and their impact on children.

The authors note several limitations, including the use of cross-sectional data, which prevents tracking individual dietary changes over time. They also point to the potential for residual confounding from unmeasured lifestyle factors and a possible underestimation of LCS intake due to the survey's data collection methods.

Journal reference:

- Seesen, M. et al. (2025) Association of low-calorie sweetened product consumption and intakes of free sugar and ultra-processed foods in UK children: a national study from 2008 to 2019. European Journal of Nutrition. 64, 230. DOI: 10.1007/s00394-025-03740-8, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-025-03740-8