A major Swedish study finds that what you eat now could shape how many chronic illnesses you face later, highlighting the power of a healthy diet to slow the march of multiple diseases in older age.

Study: Dietary patterns and accelerated multimorbidity in older adults. Image Credit: luigi giordano / Shutterstock

Study: Dietary patterns and accelerated multimorbidity in older adults. Image Credit: luigi giordano / Shutterstock

In a recent article published in the journal Nature Aging, researchers investigated the association between adhering to four different dietary patterns and multimorbidity. They found that following certain eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, was associated with a slower increase in chronic disease burden. In contrast, higher scores on the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Index (EDII), indicating diets high in pro-inflammatory foods, were linked to a faster accumulation of diseases.

Notably, in some secondary analyses, higher adherence to the Alternate Mediterranean Diet (AMED) was unexpectedly associated with a faster rate of musculoskeletal disease accumulation. However, this was not a primary outcome, and the clinical significance remains uncertain.

Background

Aging is a significant risk factor for developing chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions. In high-income countries, individuals over 70 years old experience a much greater burden of disease than younger adults. As a result, promoting healthy aging, enabling older adults to live longer and healthier lives even with chronic illnesses, has become a public health priority.

Multimorbidity, defined as having two or more chronic conditions, is an increasingly important focus in health research. Instead of emphasizing individual diseases, it highlights the overall burden experienced by the person. Researchers often categorize multimorbidity by organ systems, such as cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, and musculoskeletal.

Among lifestyle factors, diet plays a crucial role in the development and prevention of chronic diseases. Rather than looking at single foods or nutrients, examining overall dietary patterns provides a better understanding of long-term health effects due to the complex interactions between dietary components.

Some studies have shown that healthy diets like the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) are linked to lower multimorbidity, while unhealthy diets like the Western diet are linked to a higher risk. However, prior research has been limited by narrow focus, short follow-up periods, or cross-sectional designs.

This study aimed to assess how long-term adherence to several dietary patterns influences the rate of chronic disease accumulation in older adults.

About the Study

This longitudinal study used data from a Swedish cohort that included community-dwelling adults aged 60 and older. Participants were assessed at regular intervals over 15 years, with dietary data collected during the first three waves and multimorbidity tracked across all six waves.

From an initial sample of 3,363, researchers analyzed data from 2,473 individuals after excluding those with missing dietary or key demographic information.

Dietary intake was measured via food frequency questionnaires, and adherence to four dietary patterns, the Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Index (EDII), AHEI, the Alternate Mediterranean Diet (AMED), and the MIND (Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay), was calculated. Multimorbidity was defined as the number of chronic diseases and grouped by organ system (musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric).

Chronic conditions were diagnosed using clinical assessments and national registry data. Statistical analyses used linear mixed models to examine how dietary adherence affected the rate of disease accumulation over time, adjusting for potential confounders. Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the findings. Associations were also analyzed using trajectory modeling to explore differences in disease accumulation speed among subgroups.

Key Findings

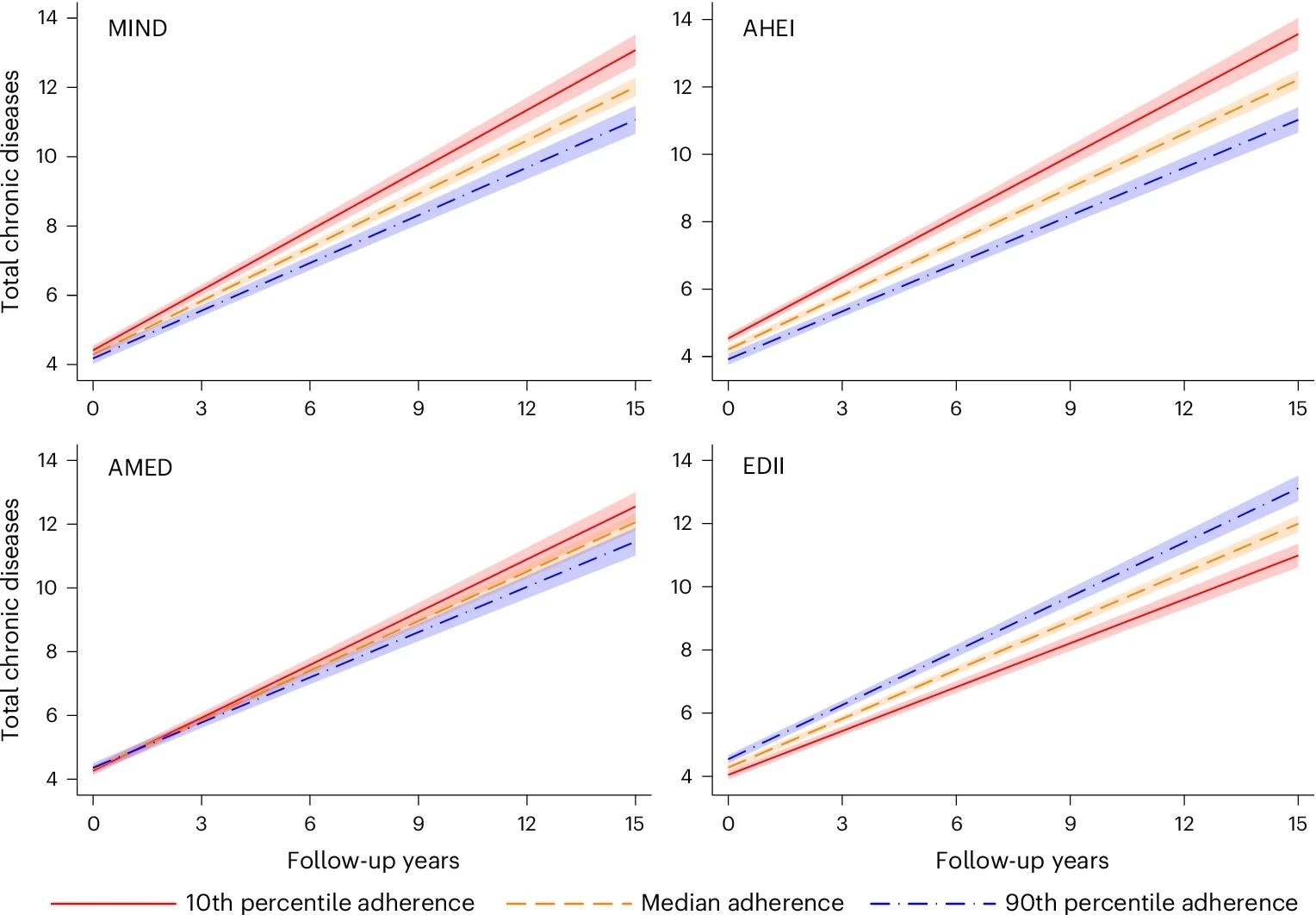

The study followed 2,473 Swedish older adults with an average age of 71.5 years over 15 years. Most participants had multimorbidity at baseline, and healthier dietary patterns such as AMED, AHEI, and MIND were linked to a slower increase in total chronic disease count, while a pro-inflammatory diet (EDII) was associated with faster accumulation.

For instance, those with the highest adherence to MIND and AHEI diets accumulated about two fewer chronic conditions over 15 years compared to those with the lowest adherence. These patterns were particularly evident for cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric conditions, but no significant associations were observed for musculoskeletal diseases across any of the dietary patterns.

Sex and age differences emerged: the benefits of healthy diets for cardiovascular health were more pronounced in females, but these sex differences were not statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. In participants over age 78, the MIND and AHEI diets showed stronger associations with reduced neuropsychiatric disease accumulation.

Sensitivity analyses supported these findings. However, when participants with multimorbidity at baseline were excluded, the associations for some dietary patterns, including MIND and AMED, were weakened and sometimes lost statistical significance.

Dietary adherence also influenced the likelihood of following faster or slower disease trajectories. For example, higher EDII adherence increased the odds of being in faster disease accumulation groups. Associations for AMED with cardiometabolic multimorbidity were weaker than for AHEI or MIND and were not statistically significant in some analyses.

Overall, AHEI generally showed the strongest protective association among the dietary patterns.

MIND: baseline range: 2–12; 1 s.d. = 1.74. AHEI: baseline range: 29.9–91.7; 1 s.d. = 9.82. AMED: baseline range: 0–9; 1 s.d. = 1.76. EDII: baseline range: −1.36 to 2.70; 1 s.d. = 0.30. Model: linear mixed model with random intercept and slope, adjusted by age (years), sex (male or female), living arrangements (alone or not), previous occupation (manual or non-manual worker), education (elementary, high school or university), tobacco smoking (never, former smoker, current smoker or unknown), physical activity (inadequate, health-enhancing, fitness-enhancing or unknown) and energy intake (kcal d−1). Data are presented as the average predicted number of chronic diseases ± 95% CIs (shaded area).

MIND: baseline range: 2–12; 1 s.d. = 1.74. AHEI: baseline range: 29.9–91.7; 1 s.d. = 9.82. AMED: baseline range: 0–9; 1 s.d. = 1.76. EDII: baseline range: −1.36 to 2.70; 1 s.d. = 0.30. Model: linear mixed model with random intercept and slope, adjusted by age (years), sex (male or female), living arrangements (alone or not), previous occupation (manual or non-manual worker), education (elementary, high school or university), tobacco smoking (never, former smoker, current smoker or unknown), physical activity (inadequate, health-enhancing, fitness-enhancing or unknown) and energy intake (kcal d−1). Data are presented as the average predicted number of chronic diseases ± 95% CIs (shaded area).

Conclusions

This study found that long-term adherence to healthy dietary patterns, particularly the AMED, AHEI, and MIND, was linked to a slower accumulation of chronic diseases, especially cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric conditions, in older adults. In contrast, a pro-inflammatory diet was associated with faster disease accumulation.

Some associations were stronger in women and the oldest participants, although none of these interactions remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

The protective effects of diet may be explained by reduced inflammation, a key factor in aging-related diseases. Strengths of the study include the 15-year follow-up, repeated dietary assessments, and robust sensitivity analyses.

Limitations involve reliance on self-reported dietary data, lack of pre-baseline diet information, potential for reverse causality, and the study’s urban, highly educated sample, which limits generalizability. Importantly, the findings highlight the organ-system specificity of diet effects, with no evidence of benefit for musculoskeletal multimorbidity.