Once driven by dramatic drops in early-life mortality, life expectancy gains are now losing momentum, signaling that today’s generations may never match the near-linear longevity climb of the past.

Study: Cohort mortality forecasts indicate signs of deceleration in life expectancy gains. Image Credit: Hyejin Kang / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, INED, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison estimated cohort life expectancy for birth cohorts from 1939 to 2000 across 23 high-income countries, using multiple forecasting methods, and assessed whether gains are decelerating.

Background

Every year of extra life shapes budgets, pensions, and family plans, yet recent headlines warn that progress may be slowing. For a century, high-income countries saw near-linear gains as vaccines, sanitation, and cardiac care reduced early and midlife deaths.

Period life expectancy summarizes mortality in a calendar year, but cohort life expectancy tracks real birth cohorts and better reflects lived longevity. Longevity also depends on economic stability, behavior, inequality, and emerging risks, including pandemics and public health crises.

Policy and planning hinge on knowing whether longevity gains are compounding, flattening, or shifting by age; further research is essential.

About the study

The analysis used age-specific death rates from the Human Mortality Database (HMD) for 23 high-income, low-mortality countries. Birth cohorts from 1939 to 2000 were included at age 20 and above, to ensure substantial observation.

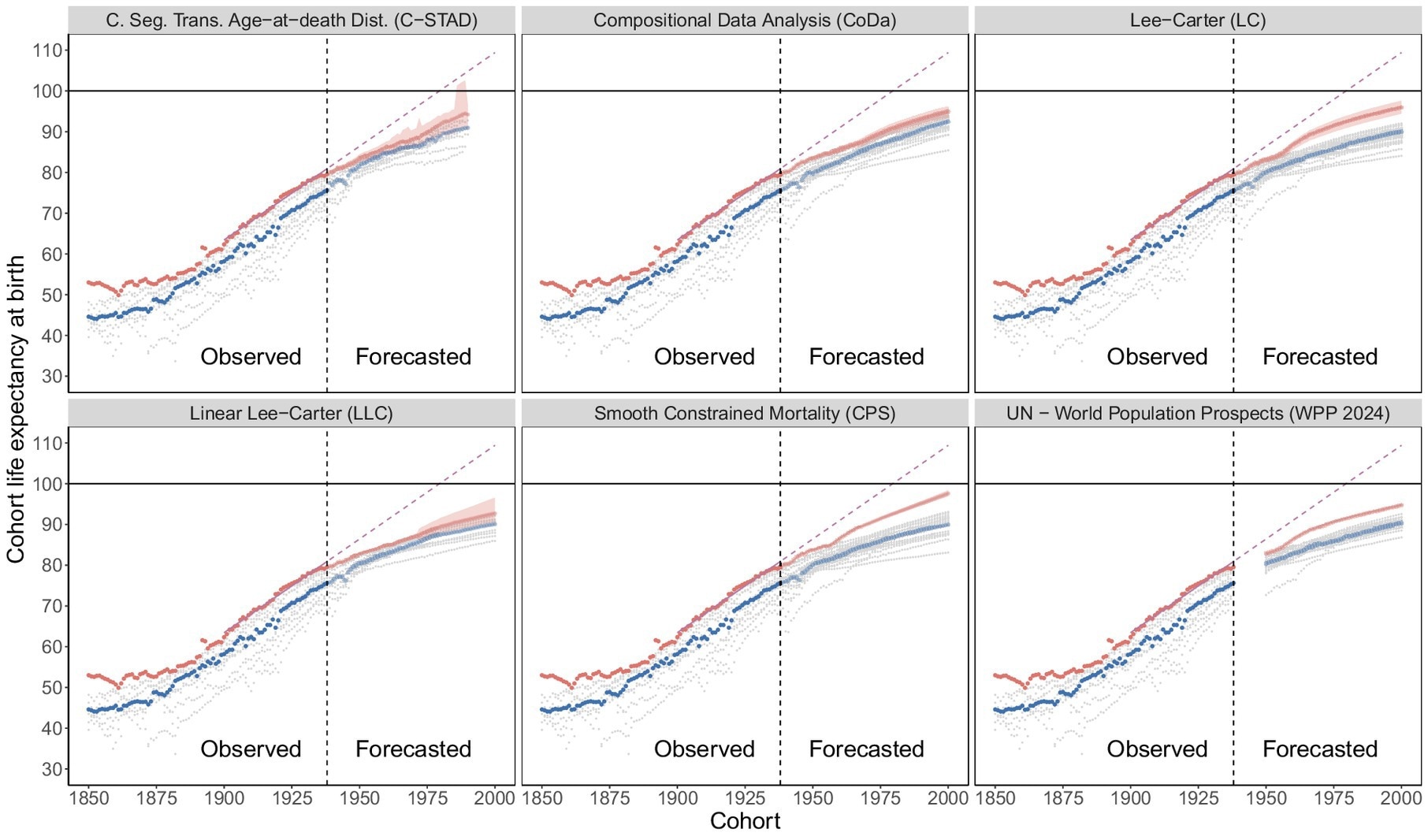

Cohort mortality was forecasted to age 100+ for accuracy, and life tables were then closed at 85+. Two modeling strategies were applied. Period-based forecasts approximated cohort mortality by extracting the Lexis diagonal and included Lee-Carter (LC), Smooth Constrained Mortality Forecasting CP-Splines (CPS), Compositional Data Analysis (CoDa), and the United Nations World Population Prospects 2024 (UN WPP 2024) medium scenario. Cohort-specific models directly captured cohort trends using the Linear Lee-Carter (LLC) and Cohort Segmented Transformation Age-at-death Distributions (C-STAD) methods.

Uncertainty was quantified with 95% bootstrapped Prediction Intervals (PIs). For interpretation, a “best-practice” series (representing the highest cohort life expectancy) and a median were summarized. An age-decomposition using Arriaga’s method apportioned cohort life expectancy changes into contributions from ages 0–5, 5–20, 20–40, 40–60, and 60–85+, with Switzerland used as a reference to limit cross-country variation. Accuracy checks compared forecast bias by predicting outcomes for cohorts born between 1919 and 1938 and contrasting those forecasts with observed values.

Study results

Across all six forecasting methods, gains in cohort life expectancy decelerated relative to the near-linear pace observed for cohorts born between 1900 and 1938. Under a linear extrapolation of those earlier gains, best-practice life expectancy would increase by about 0.46 years per cohort and reach 100 years by the 1980 birth cohort.

In contrast, forecasted best-practice gains ranged from 0.22 years per cohort with LLC to 0.29 years per cohort with CPS, with the UN WPP 2024 at 0.23. For the median across countries, gains ranged from about 0.20 to 0.27 years per cohort. This corresponds to percentage reductions compared to the optimistic trend of approximately 37%–52% for best-practice and 44%–58% for the median.

None of the cohorts born from 1939 to 2000 is projected to achieve a cohort life expectancy of 100 years.

Cohort life expectancy, observed and forecasted. Observed values and forecasted values are separated by the vertical dashed line (black) in 1938. Best-practice (red), median (blue), country-specific (gray), linear extrapolation of best-practice 1900–1938 (pink).

Across methods, the optimistic linear projection exceeded the upper bound of the 95% PI, reinforcing the slowdown signal, findings held in sensitivity analyses. Accuracy analyses indicated that any downward bias for earlier cohorts cannot fully explain these results.

Forecasts produced for cohorts born between 1919 and 1938 were compared with observed cohort outcomes. For CPS, the absolute mean deviation averaged approximately 0.36 years, compared to a later gap of roughly 2.75 years; for LC, 2.37 years versus 3.01 years.

Across methods, the observed forecast bias accounted for only a fraction of the divergence from the optimistic scenario, supporting a real deceleration rather than an artifact of underestimation.

Age decomposition pinpointed where momentum was lost. More than half of the reduction in the pace of improvement stemmed from slower gains among children aged 0–5, and over two-thirds from those under 20. These ages are fully observed for the cohorts under study, indicating that the slowdown reflects mortality trends that have already occurred rather than speculative forecasts.

Gains at older ages persisted but were not large enough to offset early-life deceleration. In a stress test that doubled future mortality improvements relative to CPS forecasts, the average improvement for currently living cohorts rose from roughly 0.20 to 0.32 years per cohort, still well below the 0.46 years per cohort observed for earlier cohorts.

Country patterns, examined through best-practice and median series, suggested that the results were not driven by a single outlier. Forecast trajectories largely continued smooth historical trends without structural breaks, and conclusions were consistent across period-based (LC, CPS, CoDa, UN WPP 2024) and cohort-specific (LLC, C-STAD) approaches.

Conclusions

Currently living cohorts in high-income countries are projected to experience a slower increase in longevity compared to earlier cohorts. The deceleration stems chiefly from diminished improvements at very young ages, with later-life progress too small to restore the previous pace.

These findings do not establish a hard biological limit, but instead underscore the combined effects of social, economic, behavioral, and medical determinants. Importantly, the authors note that these forecasts apply specifically to the 1939–2000 birth cohorts studied, and conclusions should not be generalized beyond this range.

Policies that reduce midlife risks and accelerate the prevention and treatment of age-related diseases may raise cohort life expectancy, yet are unlikely to recreate the historical, near-linear climb for these cohorts. Planning for pensions, health systems, and inequality must reflect this slower trajectory.

Journal reference:

- J. Andrade, C.G. Camarda, & H. Pifarré i Arolas. (2025). Cohort mortality forecasts indicate signs of deceleration in life expectancy gains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122 (35). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2519179122, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2519179122