New ultra–high-field brain scans reveal hidden body maps inside the visual system, showing how the brain weaves sight and touch together to build a unified sense of perception.

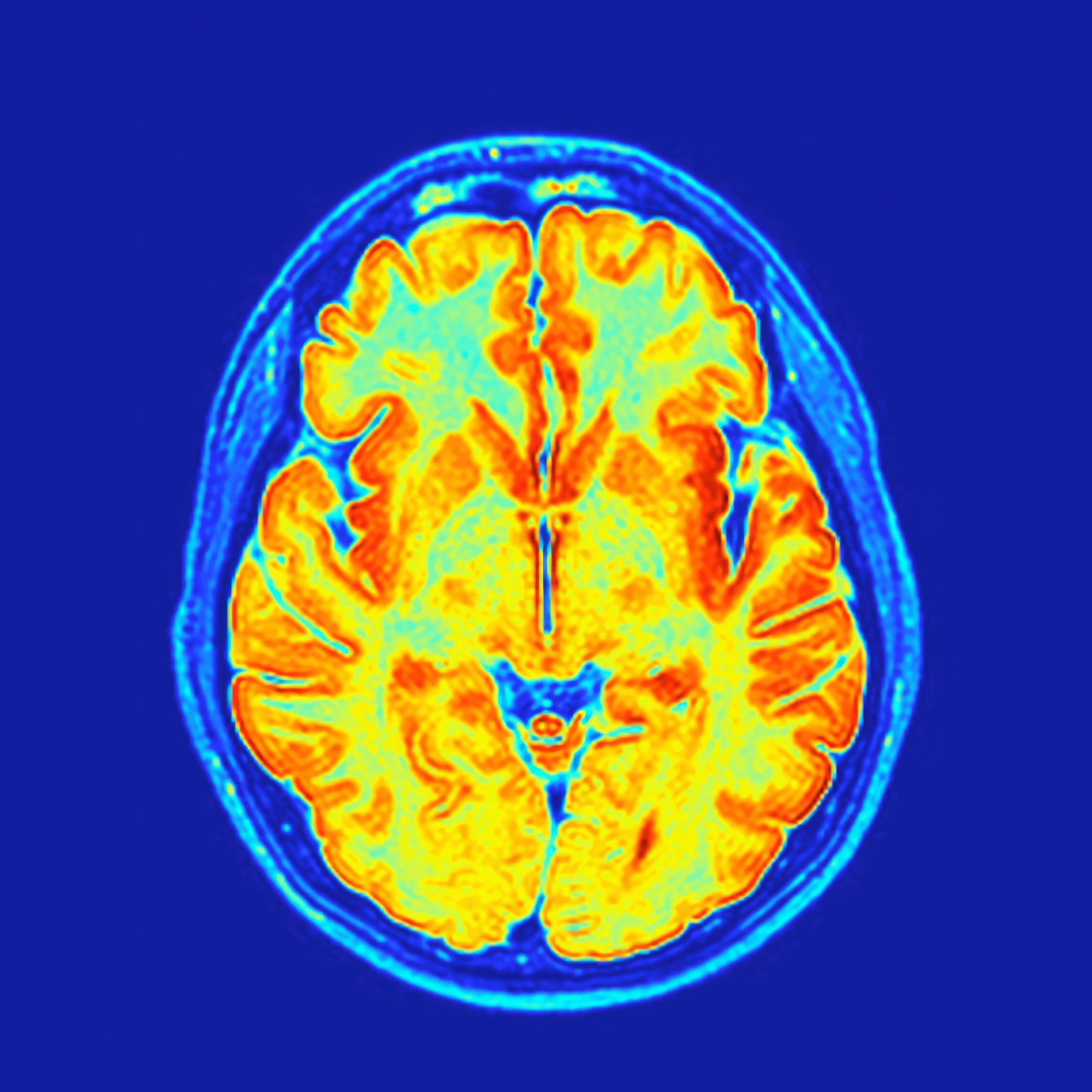

Study: Vicarious body maps bridge vision and touch in the human brain. Image credit: FocalFinder/Shutterstock.com

Study: Vicarious body maps bridge vision and touch in the human brain. Image credit: FocalFinder/Shutterstock.com

In a recent Nature study, researchers investigated how the brain integrates information from the eyes and the sense of touch to form complex maps of its environment.

Their findings revealed that the brain contains coordinated and extensive maps linking vision and touch, supporting an embodied, integrated system.

Visual and touch systems naturally interact in humans

Human perception is shaped by interactions between sensory systems, particularly the close relationship between vision and touch. When someone sees another person being touched or in pain, their somatosensory system often responds as if they themselves were touched.

Previous neuroimaging studies have shown that observing actions or touch activates body-part-specific regions in somatosensory and motor cortices, and similar cross-modal effects are also observed in higher-level visual areas. These interactions support vicarious experiences, empathy, and embodied cognition. Yet it remains unclear how the brain links the computational structures of vision and somatosensation.

Even without external stimulation, somatosensory areas may be active during self-referential, introspective, or body-focused processes. Conversely, when visual input suggests bodily interaction, the brain must translate visual information into somatosensory formats. This predicts the existence of neural regions that are tuned jointly to both visual and somatosensory reference frames.

High-resolution scans trace functional links across cortex

The researchers developed a new computational model to examine the connections between each part of the brain and the visual and somatosensory systems. They focused on two main “source” areas: the primary visual cortex, which contains a map of the visual field, and the primary somatosensory cortex, which includes a map of the body's sensory receptors.

They used high-resolution data from 174 participants in the Human Connectome Project, each of whom completed one hour of resting scans and one hour of video-watching scans.

For every tiny brain unit (voxel), the model estimated the strength of its functional connections to different locations within the primary visual cortex and the primary somatosensory cortex.

These connectivity patterns allowed the researchers to infer whether a voxel responded more like a visually tuned area, a body-part-tuned area, or a mix of both. They tested how well different models fit the data using cross-validation to ensure the findings were reliable, using an approach that automatically partitions the variance explained by visual versus somatosensory sources.

The team also performed several supporting analyses, including statistical tests of somatotopic strength, clustering to identify patterns, and checks to ensure results were consistent across different groups of participants. They also identified known visual body-selective regions to compare with the model’s predictions of multimodal (visual combined with touch) tuning.

Video viewing increases touch-linked activity in visual cortex

At rest, the model revealed widespread body-part-related organization across many brain regions, including parietal, frontal, medial, and insular areas. These maps showed the expected ordering of different body parts, such as the typical toe-to-tongue gradient.

Patterns for lower-limb, trunk, and upper-limb representations match what is known from previous somatosensory research. Notably, these orderly maps appeared even without any touching or movement, although the authors note that spontaneous resting-state activity cannot be tied to specific mental content.

During video watching, body-related connectivity became significantly stronger and spread to approximately half of the cortex. Primary sensory areas remained largely unchanged, but higher-level somatosensory and parietal regions exhibited significant increases, which aligns with how people process observed actions and touch in others.

Most strikingly, clear somatotopic tuning was observed in many visual areas, particularly in the dorsal and lateral regions, where only visual signals were expected. These visual regions contained alternating patches: some behaved more like retinotopic visual areas, while others behaved more like body-part-tuned somatosensory areas.

In visual body-selective regions, specific parts of the cortex exhibited stronger somatosensory tuning, aligning with their known roles in processing the body and actions. These effects were stronger when participants viewed video segments featuring human agents compared to scenes without people, indicating that somatotopic tuning in the visual cortex was content-dependent.

Overall, the results show that the brain contains coordinated maps linking vision and touch, supporting an integrated, embodied system.

Hybrid maps linking sight and touch

This analysis reveals that vision and touch are more closely integrated in the brain than previously assumed. The authors demonstrate that the dorsolateral visual cortex contains somatotopic structure aligned with retinotopic maps, suggesting that visual regions also house body-referenced computations.

The study directly tested two alignment hypotheses: a visuospatial alignment (linking body-part tuning to visual field location) and a categorical alignment (linking body-part tuning to visual body-part selectivity). Evidence supported both: dorsal regions showed visuospatial alignment, while ventral regions showed categorical alignment.

This alignment likely supports embodied perception, cross-modal modulation, flexible visuotactile interaction, and semantic processes linked to body representations. The findings echo mouse studies where somatosensory responses dominate the visual cortex, suggesting a possible human homologue.

Major strengths include the use of large and high-resolution datasets and naturalistic stimuli, which reveal fine-grained cross-modal architecture often missed by conventional tasks. The modelling approach also captures connectivity patterns across vision and touch with high precision.

However, uncertainties remain about the exact organizational principles of somatosensory maps, which are less orderly than visual topography, and about how these mappings evolve developmentally or adapt with training.

Despite these limitations, the study proposes a fundamental organizational principle in which aligned visual–somatosensory maps provide a neural basis for embodied, multisensory perception.

Download your PDF copy now!