Using primary human cortical tissue and cortical organoids derived from stem cells to test if severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can directly infect brain cells, researchers found significant infection of the astrocytes and not much in other cell types.

Some typical symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, are fever, runny or stuffy nose, and sore throat. Although the virus infects the respiratory system and impairs respiratory functions, there have been reports of the virus infecting other organs.

Many COVID-19 patients have shown neurological symptoms like headache, dizziness, short-term memory loss, seizures, and strokes. However, it is not known if these are because of direct infection of the neural tissue or a secondary consequence of the infection. Studies have shown that the virus can infect brain cells. Viral RNA and antibodies have been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients. SARS-CoV-2 can also infect the nasal epithelial cells and thus enter the central nervous system (CNS).

How the virus affects developing brains is yet unknown. Infants have a greater risk for infection and adverse complications. Some studies have reported children born to positive mothers become infected within a few days of birth. However, the transmission route to newborns is still unknown. There have been a few reports of placental infection of newborns, although the impact of the virus on long-term development needs to be determined. The effect of the virus on a developing brain and impacts on brain function and health require more studies.

SARS-CoV-2 infects astrocytes

Researchers from the University of California San Francisco and Gladstone Institutes in the USA, and The Aga Khan University in Pakistan, investigated if human neural cells can be infected by SARS-CoV-2. They published their results in a paper in the bioRxiv* preprint server.

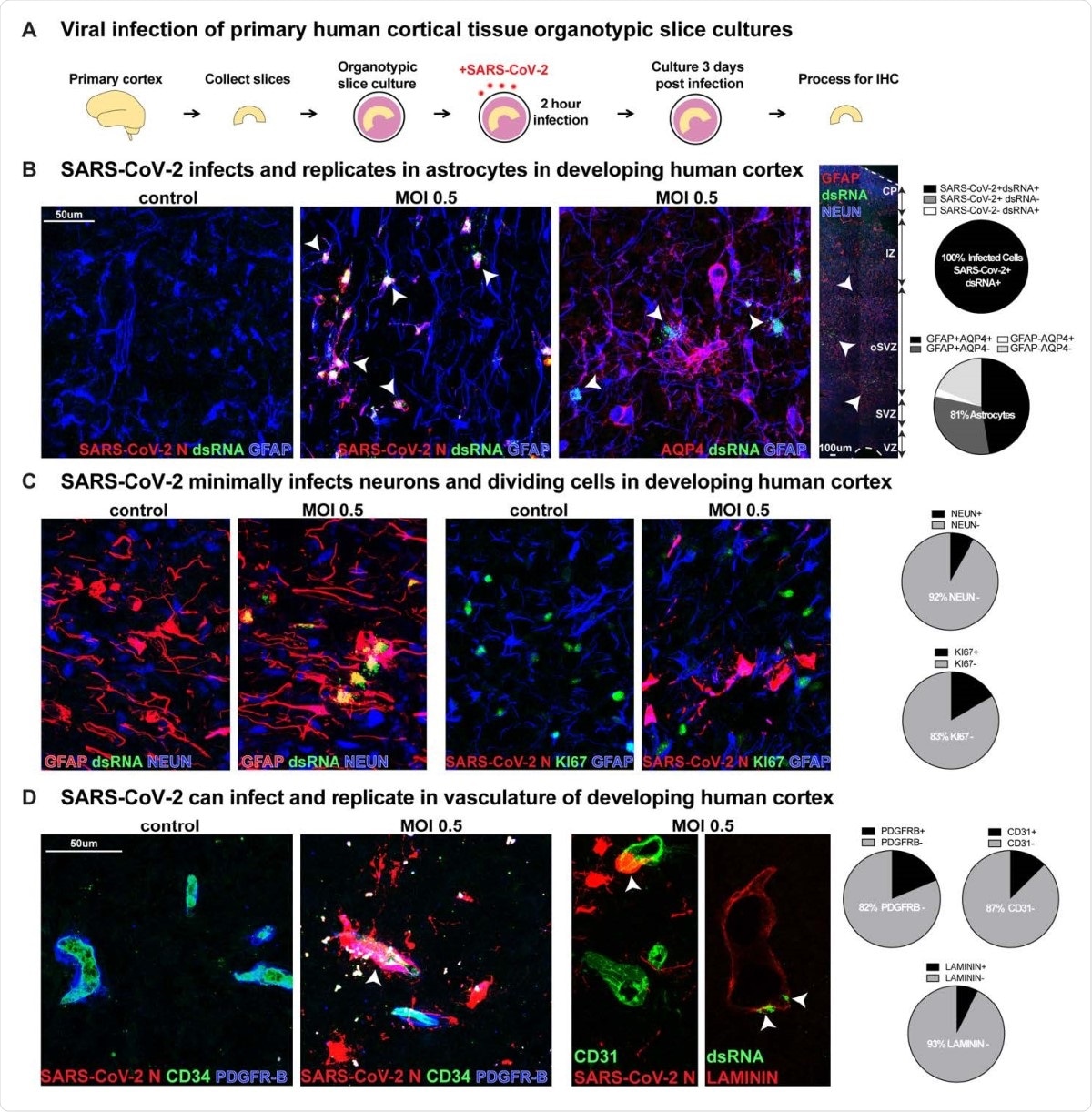

SARS-CoV-2 Infects Astrocytes in Developing Human Cortex. A) Experimental paradigm for viral infection of human cortical tissue. Primary cortical tissue was acutely sectioned and cultured at the air-liquid interface. The next day tissue was infected with SARS-CoV-2 at MOI 0.5 and cultured for 72 hours before being collected and processed. B) SARS-CoV-2 infects GFAP+AQP4+ astrocyte cells in the developing human cortex, which are predominantly located in the subventricular zone (SVZ), where >81% of cells assayed expressed markers of astrocytes. 100% of infected cells expressed both SARS-CoV-2+ nucleocapsid (N) antibody and double-stranded (ds)RNA antibody. White arrowheads indicate dsRNA+GFAP+ infected astrocytes (dsRNA+SARS-CoV-2 N+ n=31 cells, GFAP+AQP4+ n=74 cells across two biological samples and four technical replicates). C) Few other neural types were infected, as indicated by co-labeling of SARS-CoV-2 N or dsRNA, where <8% of cells assayed expressed NEUN, a marker of cortical neurons, and <17% expressed KI67, a marker of dividing cells (NEUN n=613 cells, KI67 n=186 cells across two biological samples and four technical replicates). D) Vascular cell types can also be infected where 7% of LAMININ+ blood vessels, 13% of CD31+ endothelial cells and 18% of PDGFR-ß+ mural cells have infection. White arrowheads indicate infected vascular cells (Laminin n=269 cells, CD31 n=247 cells, PDGFRB=225 cells across two biological samples and four technical replicates).

They exposed tissue slice cultures of developing human cortical samples to SARS-CoV-2 for two hours. After allowing the cells to grow for 72 hours, they tested them for the virus. They found significant infection of the astrocytes, but minimal infection on the other cell types in the neural tissue. This suggests glial cell types are more susceptible to infection compared to neuronal cell types or neuronal progenitors.

The team found that blood cells were also infected, although at a lower level than astrocytes. Blood cells are present adjacent to astrocytes, suggesting this may be a route for infection of astrocytes, which are important in blood-brain barrier formation.

They also explored which stages of cell development are more vulnerable to infection using cortical organoids infected with SARS-CoV-2 at early neurogenesis (week 5), peak neurogenesis at (week 10), early gliogenesis (week 16) and peak gliogenesis (week 22). They found significant infection of the astrocytes at week 22, but almost no infection occurred earlier, indicating the virus can infect astrocytes in the developing human cortex.

Co-factors for brain cell infection

The human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is a key entry target of SARS-CoV-2 during infection. However, ACE2 is not expressed much in the human cortex, developing or adult, nor in neural tissue. Recent studies have reported other factors, such as restriction enzymes and proteases, are also involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team found expression of extracellular glycoproteins, coronavirus restriction factors, and proteases like TMPRSS5 in different cortical cells among the various tissues, which may help with virus infection. In infected astrocytes, they found the presence of coronavirus receptors DPP4 and CD147. DPP4 is abundant in astrocytes before virus infection, suggesting it may be a key receptor in astrocyte reception.

The ability of SARS-CoV-2 to use other extracellular glycoproteins suggests the virus can infect a variety of cell types using different receptors in many organ systems, causing severe damage. In astrocytes, although the results suggest DPP4 is a key infection-mediating receptor, if not the sole receptor. DPP4 inhibition does not eliminate infection. Other proteases expressed, like TMPRSS5, FURIN, and CTSB could be alternate modes of viral entry into the brain.

Thus, the results suggest SARS-CoV-2 has the ability to infect astrocytes. Astrocytes regulate many functions in the developing and adult brain. They regulate neurotransmitter concentration and re-uptake, mediate blood-barrier function, and control neural metabolism and inflammation. Disruptions in their functioning can severely impact the brain, resulting in seizures, inability to control motor function, and even death.

Although the results of the study suggest developing astrocytes, in particular, are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, even adult astrocytes are vulnerable. Further post-mortem studies of neural tissues of patients will help understand this in more detail, including furthering our knowledge of the receptors that help viral infection.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Andrews, M. G. et al. (2021). Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for Developing Human Cortical Astrocytes. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.17.427024, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.17.427024v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Andrews, Madeline G., Tanzila Mukhtar, Ugomma C. Eze, Camille R. Simoneau, Jayden Ross, Neelroop Parikshak, Shaohui Wang, et al. 2022. “Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for Human Cortical Astrocytes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (30). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122236119. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2122236119.