Men often face higher disease and death rates, but women show better outcomes in care. This global review uncovers where health systems succeed and fail across the gender divide.

Study: Sex-disaggregated data along the gendered health pathways: A review and analysis of global data on hypertension, diabetes, HIV, and AIDS. Image Credit: Shutterstock

Study: Sex-disaggregated data along the gendered health pathways: A review and analysis of global data on hypertension, diabetes, HIV, and AIDS. Image Credit: Shutterstock

In a recent article published in the journal PLOS Medicine, researchers found that sex differences in burden, access, and outcomes are complex and vary by country, condition, and stage of the health pathway. In many contexts, males face an excess burden of increased prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and lower access to diagnosis and treatment.

Gender and sex shape health outcomes through various factors, including patterns of health service use, bodily responses to risk exposure, and rates of exposure to environments and risk factors. Understanding differences in health outcomes, risk exposure, and health service use by gender identity and sex could help identify effective interventions to reduce health inequities. However, gender identity and sex are often conflated and confused in health surveys.

Consequently, analyzing survey data becomes challenging. Moreover, only a few surveys report on gender identity beyond the simple binary (male/female). Disaggregating data along a health pathway (from risk exposure to death, including disease prevalence and care cascade) could provide a systematic and holistic view of gender- and sex-based health inequities and identify opportunities for tailored interventions.

About the Study

The researchers analyzed sex-disaggregated data from global surveys and datasets, interpreting observed differences through a gender-informed lens. While the datasets themselves were disaggregated by sex (male/female), the authors acknowledged that the data could not fully distinguish between biological and gendered social influences. The study examined eight health conditions but had sufficient care cascade data for only three: HIV/AIDS, hypertension, and diabetes. Disease prevalence, risk factors, and mortality data came from the Global Burden of Disease dataset.

Risk factors for HIV/AIDS and diabetes were selected based on their global mortality burden, with age- and sex-disaggregated data. For hypertension, the leading cardiovascular risk factors were used. The care cascade included diagnosis, treatment, and disease control. Data sources included the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (hypertension), STEPwise Approach to NCD Risk Factor Surveillance (diabetes), and UNAIDS (HIV/AIDS). Some data were collected as "country-years," where countries contributed multiple years of observations.

Findings

Sex-disaggregated data on risk factors, disease prevalence, and mortality were available for all three conditions across 204 countries. However, care cascade data varied: hypertension (200 country-years), diabetes (39), and HIV/AIDS (76).

Hypertension risk factors included high sodium intake, high fasting plasma glucose (FPG), smoking, obesity, and overweight. Males had significantly higher smoking rates in 176 countries (except Bhutan), while obesity rates were higher in females in 130 countries. Overweight prevalence was largely similar across sexes.

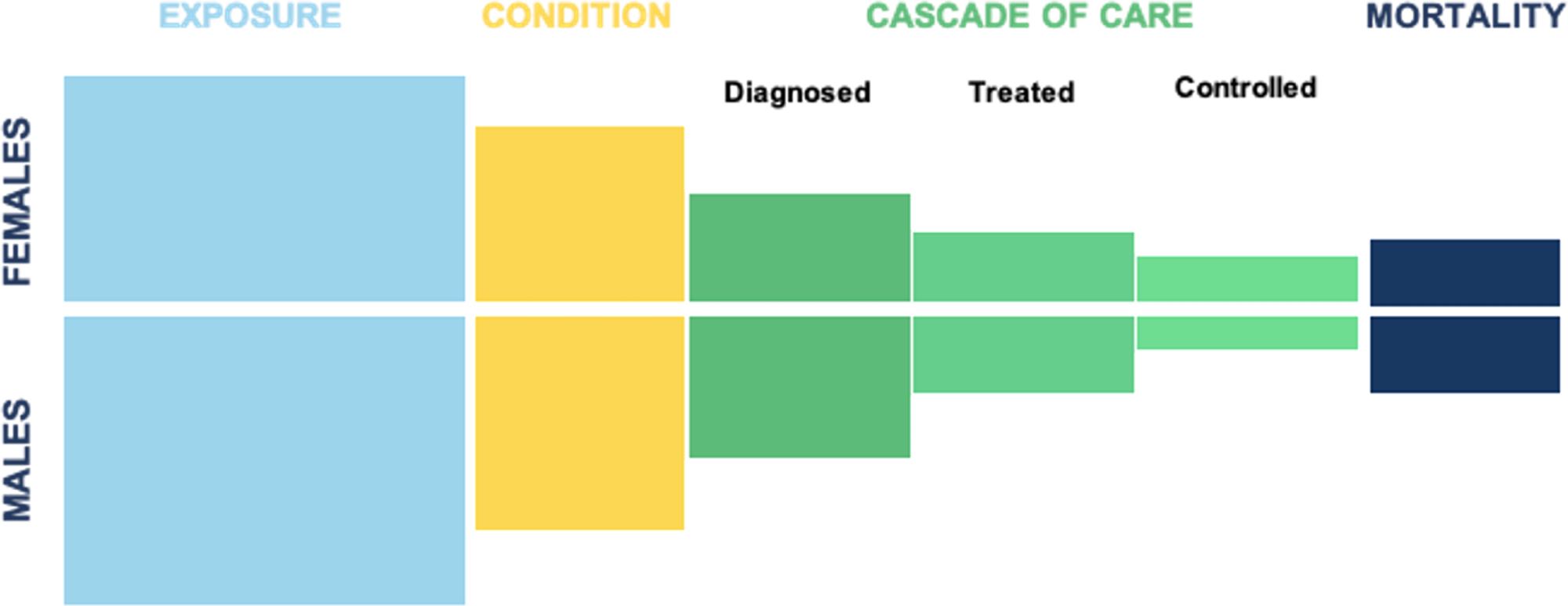

Illustration of the health pathway.

Illustration of the health pathway.

Global hypertension prevalence was comparable, with exceptions in eight countries where males had higher prevalence. India showed higher hypertension in females aged 70–79. No significant global sex differences were found in the hypertension care cascade, though some countries had higher diagnosis or treatment rates among females in specific age groups.

In Uzbekistan, Iran, and Peru, women aged 30–39 had higher hypertension control rates. Male hypertension mortality rates were higher in 107 countries, especially in high- and upper-middle-income countries. Regional differences emerged across diseases—for example, male HIV/AIDS and diabetes deaths were more common in Europe, Central Asia, and Latin America, while higher female deaths occurred in the Middle East and North Africa.

Diabetes risk factors included FPG, insulin/drug use, overweight, obesity, smoking, and low physical activity. Physical inactivity was similar across sexes, though some countries showed differences. Diabetes prevalence varied: higher in males in 61 countries and females in 10. Care cascade differences were limited, except in Cape Verde, where females had better outcomes in some age groups. Mortality from diabetes was higher in males in 100 countries and in females in 9, with 95 countries showing no difference.

For HIV/AIDS, risk factors included drug use, unsafe sex, and intimate partner violence. Drug use was higher in males in 139 countries and in females in a few (e.g., Syria, China, Iceland). Unsafe sex was more common among females in 113 countries. HIV prevalence was higher in males in 114 countries and in females in 28. HIV care cascade data (not age-disaggregated) showed better outcomes for females in 9, 20, and 21 countries (diagnosis, treatment, and control, respectively). Lebanon was an exception, with males performing better in treatment and control. HIV/AIDS deaths were higher in males in 131 countries and in females in 25.

Conclusions

The findings reveal significant sex differences along the health pathway. In many countries, males have higher disease prevalence and mortality and lower rates of care-seeking and treatment adherence. However, differences in care cascade performance were less consistent and more limited than those in disease burden and risk factors.

The study cautions that biological sex is not the sole driver of these differences—social norms, health system structures, geography, and policies also play a substantial role. Limitations include incomplete datasets for many conditions and countries, underrepresentation of non-binary individuals and marginalized populations, and inconsistent definitions across surveys.

Researchers call for more comprehensive and standardized global data, disaggregated by age, sex, and other intersectional factors such as income, location, ethnicity, and disability. Without such data, the ability to design gender-responsive interventions is limited.

Ultimately, the study underscores the need for inclusive, intersectional data to develop more equitable health policies and interventions worldwide.