A growing body of human, genetic, and experimental evidence suggests that suPAR may not only signal disease risk but also actively contribute to organ damage, raising new questions about its role as a clinical biomarker and therapeutic target.

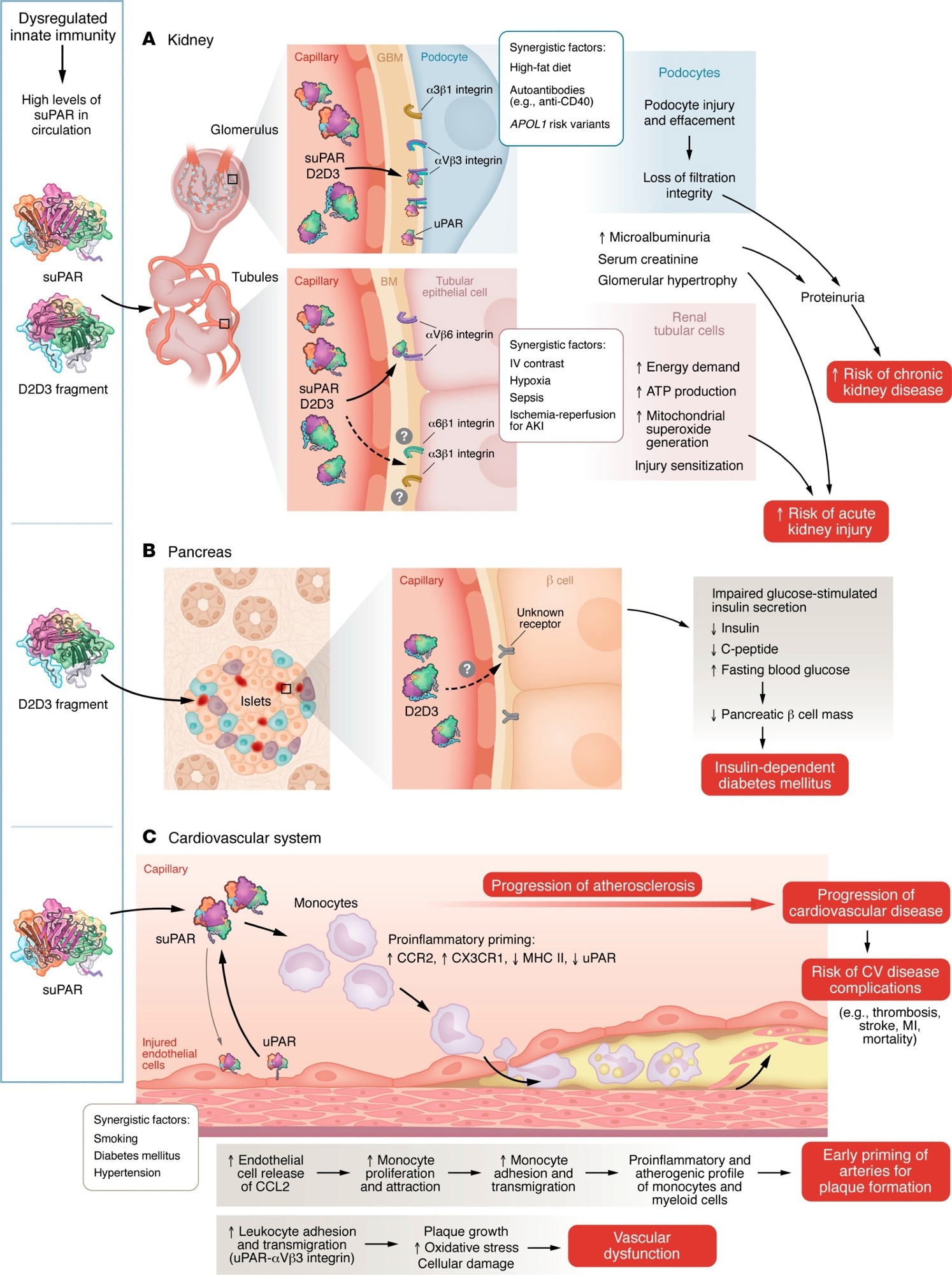

uPAR and its associated proteins induce multiorgan injury. Dysregulation of innate immunity caused by various physiological challenges, such as diabetes, hypertension, viral and bacterial infections, or smoking, leads to elevated suPAR levels and/or production of the D2D3 protein. Models illustrate the mechanisms through which these proteins cause injury to the kidney (A), pancreas (B), and cardiovascular system (C).

In a recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers reviewed the role of the soluble form (suPAR) of the uPAR and related proteins in diabetes and heart and kidney diseases.

Dysregulated or overactive innate immune responses leading to chronic inflammation are central features of disorders such as cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Interleukins, chemokines, interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, inflammasome activation, complement dysregulation, and toll-like receptor signaling are key contributors to these processes. uPAR is a multiligand, membrane-bound receptor expressed on immune and endothelial cells, where it regulates immune activation, cell adhesion, and tissue remodeling.

uPAR undergoes glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor cleavage and proteolytic processing to generate circulating proteins, including suPAR and the fragments D1 and D2D3. Unlike suPAR, D1 and D2D3 are not detectable in healthy individuals but appear in patients with kidney disease and cancer. Despite structural differences, all uPAR-derived circulating proteins participate in immune signaling and integrin-mediated cell activation. The reviewed work focused on the contribution of these proteins to kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

suPAR as a Biomarker and Mediator in Kidney Disease

Bone marrow–derived immature myeloid cells and neutrophils are considered the primary source of suPAR during acute immune activation, making circulating suPAR a marker of systemic innate immune activity rather than kidney-specific injury. Elevated suPAR concentrations have been consistently associated with increased risk of kidney disease and faster progression of renal function decline.

One study reported that individuals in the highest quartile of suPAR levels experienced an annual decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 4.2 mL/min/1.73 m2, and those with preserved baseline kidney function had more than a threefold higher risk of progressing to stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD). Across multiple cohorts, suPAR was the only biomarker independently associated with kidney function decline after adjustment for age, baseline eGFR, race, diabetes, hypertension, and proteinuria.

Genetic evidence further supports a role for suPAR in kidney disease. A genome-wide association study identified a missense variant (rs4760) in the PLAUR gene associated with increased circulating suPAR levels. Mendelian randomization analyses using this variant provided evidence consistent with a causal contribution of genetically predicted suPAR levels to CKD and atherosclerotic phenotypes, while acknowledging methodological limitations.

Despite these findings, suPAR measurement remains controversial in nephrology. Kidney dysfunction itself may contribute to elevated suPAR levels, and suPAR is not cleared primarily by the kidneys, unlike creatinine or cystatin C. Additionally, there are no FDA-approved assays for suPAR, and current enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays may detect both suPAR and D2D3, complicating interpretation. Standardized assays and composite biomarker approaches will be required before routine clinical use can be considered.

suPAR, D2D3, and Systemic Effects Beyond CKD

Experimental evidence suggests that suPAR may influence renal tubular cell metabolism. In vitro studies have shown that suPAR increases ATP production, mitochondrial superoxide generation, and energetic demand in proximal tubular epithelial cells, potentially sensitizing them to injury and helping explain clinical associations with acute kidney injury (AKI).

Clinical studies support these associations. In patients undergoing coronary angiography, those with the highest suPAR levels had increased risks of AKI and mortality. Similarly, in sepsis-associated AKI, suPAR levels above 12.7 ng/mL were linked to higher risks of renal replacement therapy and death, with experimental data suggesting immune-mediated mechanisms such as enhanced T cell infiltration.

The uPAR fragment D2D3 has been implicated in both kidney injury and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Mice overexpressing D2D3 developed progressive kidney disease and insulin-dependent diabetes without dietary manipulation. In vitro and human islet studies showed that D2D3 inhibited glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Observational data further indicate that diabetes is associated with increased risks of hematological malignancies and mortality, suggesting broader systemic consequences of uPAR-related signaling.

suPAR in Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Progression

Multiple cohort studies have demonstrated associations between elevated suPAR concentrations, subclinical atherosclerosis, and future cardiovascular events. Unlike acute-phase reactants such as interleukin-6 or C-reactive protein, suPAR levels remain stable during acute illness and show minimal circadian variation. suPAR has consistently outperformed traditional inflammatory markers in predicting heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atherosclerosis across diverse populations.

Genetic studies reinforce these observations. Two missense variants in PLAUR (rs2302524 and rs4760) have been associated with circulating suPAR levels, and Mendelian randomization analyses using rs4760 suggest that higher suPAR levels increase the risk of myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, and coronary artery disease. Replication of these findings across trans-ancestry datasets supports, but does not definitively establish, a causal role.

Therapeutic Implications and Knowledge Gaps

Overall, the review highlights the interconnected mechanisms by which uPAR, suPAR, and D2D3 contribute to inflammation-driven organ damage across kidney, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases. Whether therapeutic strategies aimed at lowering suPAR, inhibiting uPAR signaling, or removing pathogenic fragments such as D2D3 will translate into clinical benefit remains uncertain, given the lack of interventional human data.

Currently, no approved therapies specifically target suPAR, but an anti-suPAR monoclonal antibody (WAL0921) is being evaluated in phase II clinical trials, reflecting growing translational interest. As understanding of uPAR-related signaling expands, these proteins may emerge as targets not only in kidney disease but across a broader spectrum of inflammatory and cardiometabolic conditions.

Journal reference:

- Reiser J, Hayek SS, Sever S (2026). The role of suPAR and related proteins in kidney, heart diseases, and diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 136(1), e197141. DOI: 10.1172/JCI197141, https://www.jci.org/articles/view/197141