A simple finger-prick dried blood test accurately tracked Alzheimer’s-related brain changes in research settings, pointing to a future role in widening access to early screening while confirmatory testing remains essential.

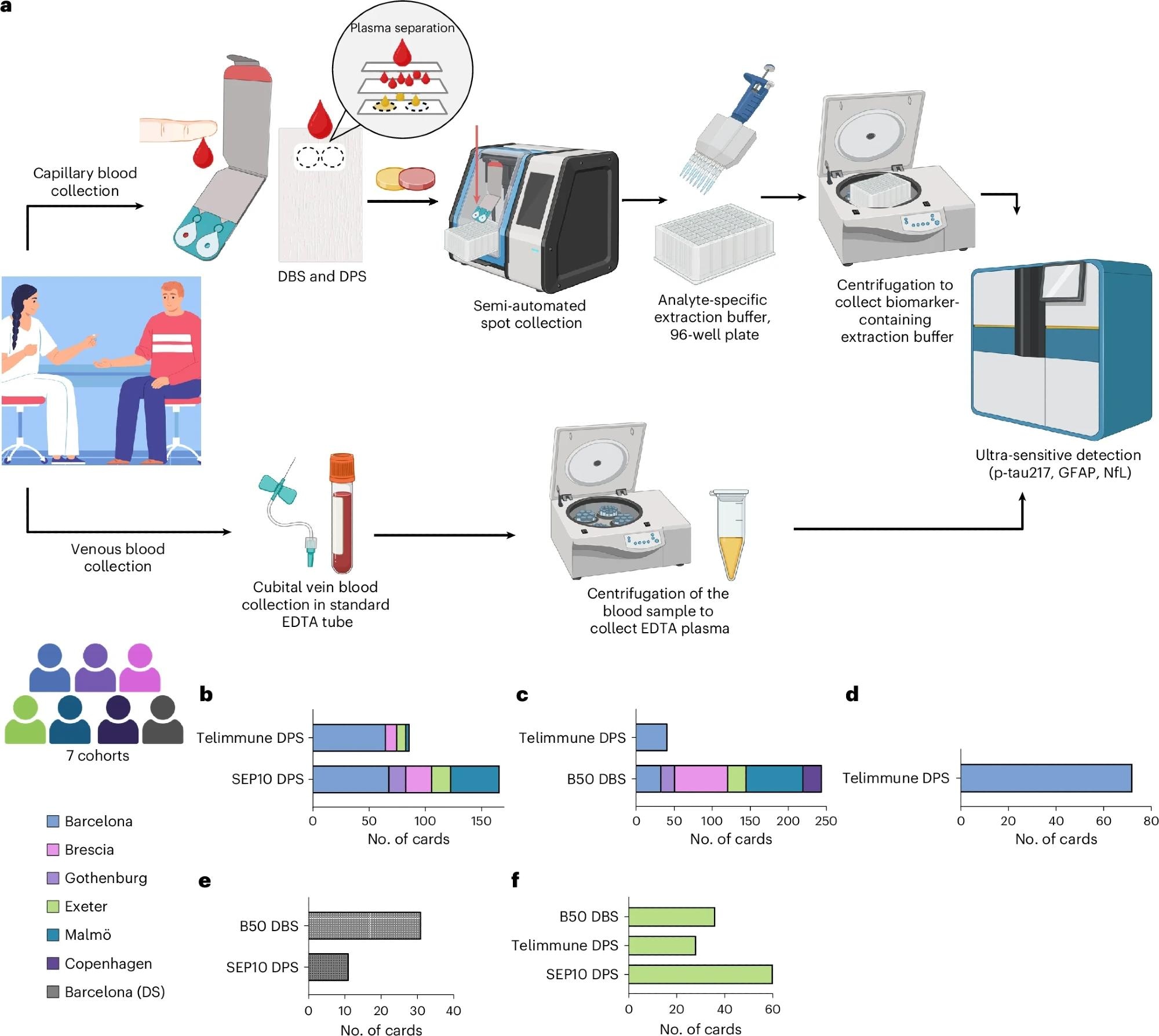

a, Collection and processing of venous plasma and capillary DPS and DBS samples. For DPS and DBS sample collection, a finger prick was carried out by trained study personnel and a few drops of capillary blood were spotted onto DPS and DBS collection devices. DPS and DBS were collected via semi-automated spot collectors and incubated with analyte-specific extraction buffer in a 96-well filter plate. After incubation and centrifugation, the eluate was immediately measured using ultrasensitive immunoassays on the single molecule array platform. b–f, Participant numbers and collection device numbers per cohort: capillary p-tau217 (b), capillary GFAP (c), capillary NfL (d), DS cohort (e) and self-sampling cohort (f). Panel a created using BioRender.com.

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Medicine, a group of researchers evaluated whether dried capillary blood, collected as dried plasma spots (DPS) and dried blood spots (DBS), can accurately quantify Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers compared with venous plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Diagnostic Challenges and Rationale for Capillary Blood Testing

Dementia affects millions of people worldwide, with Alzheimer’s disease accounting for most cases. This condition affects families, caregivers, and healthcare systems. To confirm the presence of brain amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau, tests such as CSF analysis or positron emission tomography (PET) are needed. These methods can be costly and invasive, or simply hard to access.

There is a growing number of blood tests available, such as plasma phosphorylated tau at amino acid 217 (p-tau217). However, drawing venous blood requires trained staff, rapid processing, and cold-chain storage. Testing with a simple finger prick would make biomarker testing more accessible and equitable. Nevertheless, analytical accuracy, sampling workflows, and biomarker cut-off thresholds must be rigorously validated before such approaches can be implemented in clinical practice.

Study Design and Biomarker Measurement Strategy

In the multi-center Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease using Dried Blood (DROP-AD) project, researchers enrolled 337 participants from seven European sites, including cognitively unimpaired adults, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease, non-AD dementias, and people with Down syndrome (DS), who have a high genetic risk for AD.

Fingertip capillary blood was collected on cards as DPS and DBS, with 304 participants providing paired capillary and venous samples. Venous plasma was stored at −80 °C and shipped on dry ice, while dried blood cards were transported at room temperature to a central laboratory.

Biomarkers measured using the single-molecule array (Simoa) platform included p-tau217 from DPS, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) from DBS, and neurofilament light (NfL) from DPS, all collected on a plasma-optimized card. Clinical characterization relied on standard cognitive testing, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), alongside CSF biomarkers such as CSF p-tau181/Aβ42 or CSF Aβ42/Aβ40, which served as biological reference standards. Analyses assessed correlations between capillary and venous biomarkers, group differences by clinical status, and diagnostic performance using receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (AUC), as well as exploratory positive and negative predictive values using a two-cut-off strategy.

Performance of Capillary Biomarkers Compared With Venous and CSF Measures

Across pooled cohorts, venous plasma p-tau217 correlated strongly with capillary p-tau217, with the highest correlations observed at moderate and high analyte concentrations. Performance was weaker at low concentrations, where diagnostic discrimination is inherently more difficult. Capillary p-tau217 increased with clinical severity and showed expected correlations with age and MMSE, mirroring those observed in venous plasma.

Capillary DPS p-tau217 demonstrated good accuracy for predicting CSF biomarker positivity, though performance was lower than venous plasma measurements. A two-cut-off approach enabled prioritization of sensitivity at lower thresholds and specificity at higher thresholds, allowing most individuals to be classified while reserving an intermediate range for confirmatory testing. This supports a potential triage role rather than standalone diagnostic use.

Markers of astroglial and axonal injury also translated well to capillary formats. Capillary DBS GFAP and capillary DPS NfL showed strong correlations with their venous plasma counterparts and tracked age and cognition in expected directions, indicating that card-based sampling can capture relevant neurodegenerative biology.

Utility in Down Syndrome and Practical Considerations

Capillary biomarker testing performed well in participants with Down syndrome, a group at high risk for AD who may face barriers to venous blood draws. Capillary p-tau217 and GFAP distinguished dementia from asymptomatic states and correlated well with venous measures, highlighting potential equity benefits.

Short-interval reproducibility was similar between supervised and unsupervised finger-prick collection, suggesting the feasibility of self-collection under controlled conditions. However, practical challenges remain. Collection failures occurred in 15 to 25 percent of cases, dilution effects complicated direct comparison with venous concentrations, and reliable correction factors could not be established. Measurement of Aβ42 was limited by low signal, although Aβ40 was detectable.

Implications for Clinical Use and Future Directions

Overall, finger-pricked dried blood cards provided biologically meaningful measurements of AD-related biomarkers under research conditions. Capillary p-tau217, GFAP, and NfL were tracked to assess disease severity, correlated with venous and CSF measures, and supported classification across clinical groups, including individuals with Down syndrome.

Despite these promising results, dilution effects, analytical variability, and incomplete validation of diagnostic cut-offs currently limit clinical applicability. Dried blood testing is not yet suitable for patient management but may serve as an initial screening or triage tool to identify individuals who would benefit from confirmatory PET imaging or CSF testing. At present, its strongest role lies in research, population screening, and epidemiological studies. Future work will focus on protocol optimization, broader validation, and the development of robust two-cut-off diagnostic pathways.