New research reveals how aquaculture’s nutritional promise is shaped by global trade patterns and why rethinking fishmeal use and exports could help deliver essential nutrients to populations that need them most.

Study: Global nutritional equity of fishmeal and aquaculture trade flows. Image Credit: OTABR / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers evaluated how global aquaculture production and trade affect the equitable distribution of essential nutrients across nutritionally vulnerable countries.

Aquaculture Growth and Global Micronutrient Needs

Can the world’s fastest-growing food sector help end global malnutrition, or is it quietly deepening inequality? Aquaculture accounts for approximately 42% of global aquatic animal food production by edible weight, averaged over 2015–2019, and global seafood consumption has increased twofold over the last 50 years. By providing essential nutrients such as iron, zinc, vitamin B12, and iodine, fish and other aquatic foods are vital for supporting billions of people who continue to lack these nutrients. Food insecurity does not only relate to the supply of food; it also concerns accessibility. As global trade expands, fish and fishmeal increasingly cross borders. Understanding whether this trade supports or undermines nutrition equity is critical. Further research is needed to assess how trade policies can better prioritize human health.

Data Sources, Nutrient Metrics, and Modeling Approach

The researchers examined global aquaculture production and trade flows between 2015 and 2019 by combining two large datasets: the Aquatic Resource Trade in Species database and the Aquatic Food Composition Database. These databases provided information on more than 2,800 aquatic species and over two million trade transactions.

The study analyzed essential vitamins and minerals, including calcium, folate, iodine, iron, magnesium, niacin, selenium, thiamin, vitamin A, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin E, and zinc. Nutrient supply was converted into annual Recommended Dietary Allowances for women of reproductive age, a group particularly vulnerable to micronutrient deficiencies.

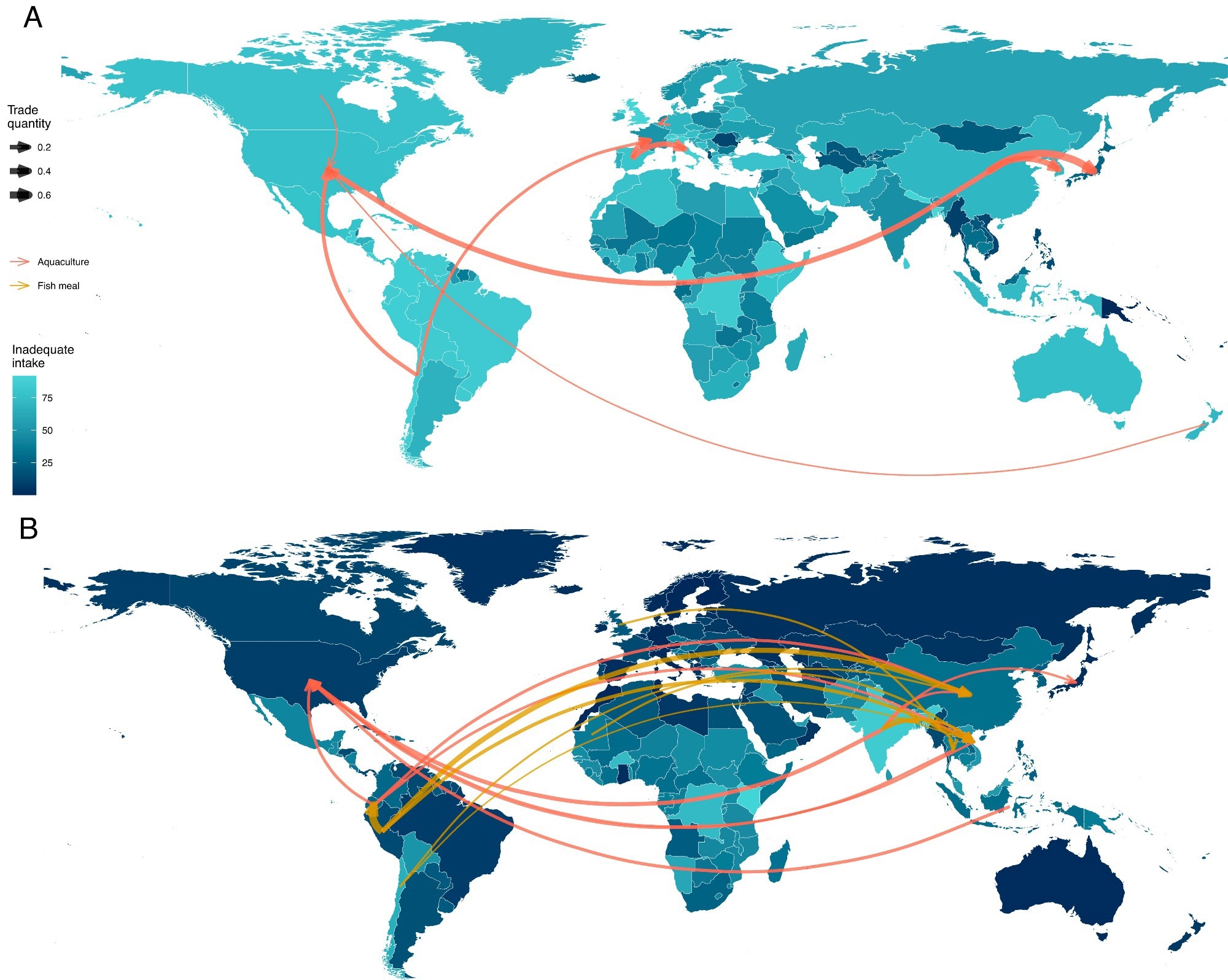

Countries’ nutritional vulnerability was defined using the prevalence of inadequate nutrient intake. Nations were classified as very low, low, medium, high, or very high vulnerability based on population nutrient deficiencies.

The study estimated domestic nutrient retention, international trade flows of fishmeal and farmed fish, and net nutrient gains and losses. It also modeled hypothetical scenarios in which wild fish used for fishmeal or exported farmed fish were retained domestically for direct human consumption. These scenarios allowed the researchers to compare actual trade patterns with alternative nutrition-focused strategies.

Top 10 trade flows by edible weight of selected taxa–nutrient pairs. Vitamin E in traded bivalve network (A) and vitamin B12 in traded shrimp network (B) represent lower and upper ends of inequitable trade, respectively. Country colors represent the proportion of the population with inadequate nutrient intake from low (green) to high (blue). The trade flows represented by arrows in the figures account for nearly half of total traded weight in taxa (48.2% in bivalves; 44.1% in shrimp). The color of arrows represent fishmeal (yellow) and farmed fish trade (red). Increasing arrow width represents higher amounts of total traded nutrients. No fishmeal trade flows are represented in bivalves which belong to non-fed aquaculture taxa.

Nutrient Production, Trade Flows, and Equity Patterns

Across the 14 nutrients studied, global aquaculture production provided, on average, sufficient nutrients annually to meet the needs of approximately 347 million people, rather than simultaneously across all nutrients. For specific nutrients such as vitamin B12, production could theoretically meet the needs of up to 2.7 billion individuals. These findings highlight aquaculture’s enormous nutritional potential.

Importantly, most aquaculture-produced nutrients (about 76.8%) were retained within producer countries. Freshwater farmed fish showed especially high domestic retention, exceeding 90%. This suggests that aquaculture can significantly strengthen local nutrition in producing nations.

However, trade patterns revealed important inequities. Between 2015 and 2019, 62.9% of fishmeal production was traded internationally, compared with only 14.9% of farmed fish. The fishmeal trade was highly globalized, linking wild-capture fisheries to aquaculture industries abroad.

Countries that experienced net nutrient gains from trade tended to have lower nutritional vulnerability than those that experienced net nutrient losses. Nations such as the United States, Japan, and France gained the equivalent of millions of individuals' annual nutrient needs, whereas Peru, Chile, and Norway experienced significant net nutrient losses.

A large proportion of countries involved in nutrient trade are nutritionally vulnerable. Approximately 57.7% of traded fishmeal nutrients and 66.3% of traded farmed fish nutrients were exported from countries with high or very high inadequate nutrient intake. In many cases, nutrients flowed from more vulnerable to less vulnerable nations, raising concerns about equity.

Vitamin B12 in farmed fish was frequently exported from highly vulnerable countries to nutritionally secure nations. Vitamin B12 deficiency has been shown to adversely affect child development and to have significant public health implications.

In contrast, the iron trade via fishmeal appeared more balanced because both exporting and importing countries often had high iron-deficiency rates. Still, final farmed fish products often ended up in relatively more secure countries, potentially diverting iron from vulnerable populations.

The study also examined hypothetical scenarios. If fish used for fishmeal were repurposed for direct human consumption, they could meet the annual nutrient needs of 31 million people globally. Retaining exported farmed fish domestically could meet nutrient needs for about 36 million people under modeling assumptions rather than observed policy outcomes, indicating somewhat greater total potential than repurposing fishmeal, although repurposing fishmeal could produce larger proportional benefits in certain countries. These findings reveal a fundamental trade-off: using fish for animal feed supports aquaculture growth but may limit direct human nutritional benefits in vulnerable regions.

The authors emphasize that these estimates are conservative and subject to uncertainty because calculations focused only on edible muscle tissue; Recommended Dietary Allowances may exceed average physiological requirements; nutrient bioavailability varies; dietary substitution effects were not modeled; and aquatic foods represent only one component of overall diets.

In some small-island and specific national contexts, including Tuvalu, Seychelles, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, Kiribati, Peru, Iceland, and Denmark, repurposing fishmeal inputs could nearly eliminate inadequate nutrient intake. More broadly, small-island, South American, and West African regions were highlighted as potentially benefiting from alternative trade strategies rather than guaranteed elimination of deficiencies.

Policy Implications for Nutrition-Sensitive Trade

Aquaculture holds tremendous potential to combat global micronutrient deficiencies, yet current trade patterns often shift nutrients away from nutritionally vulnerable populations. While domestic retention of farmed fish supports producer-country nutrition, international trade frequently benefits more nutritionally secure nations. Repurposing a portion of wild fish used in fishmeal and rethinking export policies could substantially reduce inadequate nutrient intake in vulnerable countries. To accomplish Sustainable Development Goal 2, “Zero Hunger,” policymakers may need to develop nutrition-sensitive trade policies. Anchoring aquaculture growth to public health objectives could help ensure that aquatic foods benefit those who require them most, while acknowledging the economic, environmental, and food-system trade-offs highlighted by the researchers.

Journal reference:

- L.G. Elsler, J.A. Gephart, J. Zamborain-Mason, T. Cashion, M. Troell, R.L. Naylor, R.A. Bejarano, & C.D. Golden. (2026). Global nutritional equity of fishmeal and aquaculture trade flows. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 123(7). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2506699123 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2506699123