New evidence suggests that trapping iron in unusable forms may starve vulnerable neurons, challenging decades of thinking about iron toxicity in Parkinson’s disease and opening new therapeutic questions.

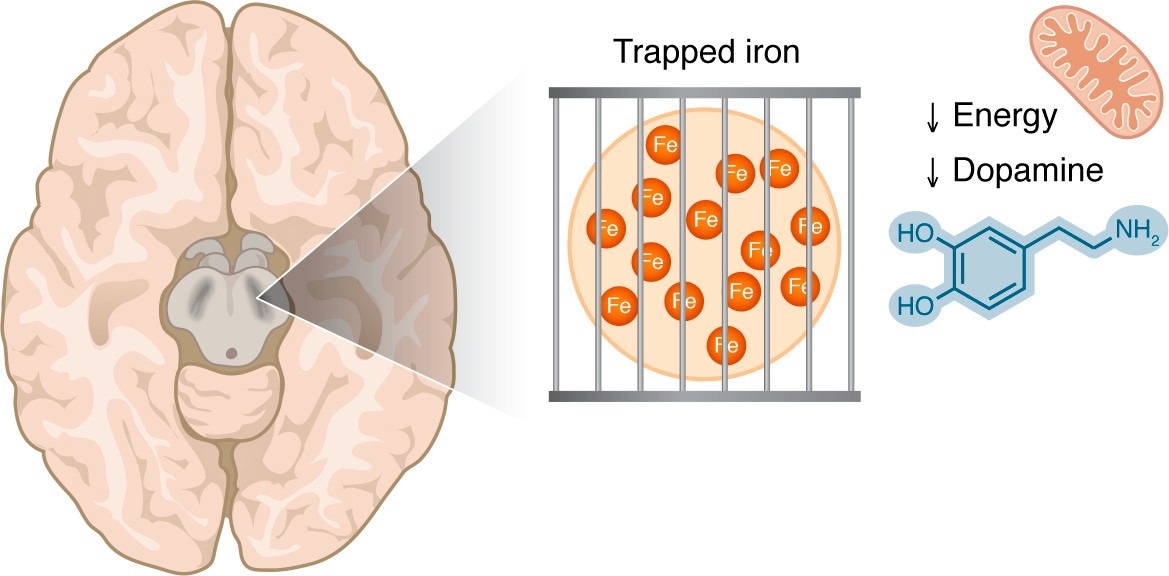

Iron accumulation in the substantia nigra is visible by MRI techniques in patients with PD. This iron may be in a trapped form, making it unavailable for the iron-dependent biological processes that are critical in dopaminergic cells, including mitochondrial respiration and dopamine synthesis.

In a recent perspective published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers discussed evidence that challenges a long-standing scientific belief that Parkinson’s disease is commonly hypothesised to be driven by toxic iron overload in the brain. They argued instead that the disease could involve a functional iron deficiency, in which biologically usable iron is low despite high total iron and may coexist with regionally elevated iron signals. Restoring iron availability, rather than removing iron, could represent a possible avenue of treatment.

For decades, abnormal iron accumulation has been linked to Parkinson’s disease, particularly in the substantia nigra, the brain region most affected in those with the condition. This association led to the dominant hypothesis that excess iron drives neurodegeneration through oxidative stress and iron-dependent cell death pathways such as ferroptosis, although the causal role of ferroptosis in Parkinson’s disease remains debated.

Recent clinical trials suggest that chelating iron with the brain-penetrant agent deferiprone can worsen symptoms, especially in patients who have not yet initiated dopaminergic therapy. These unexpected findings have forced a reconsideration of the role of iron in Parkinson’s and opened the door to an alternative explanation, functional iron deficiency. In such cases, total iron levels are normal or perhaps elevated, even as bioavailable ferrous iron (Fe2+), which is essential for cellular processes, is insufficient.

From dopamine replacement to iron biology

The modern treatment of Parkinson’s disease began with the discovery that levodopa (L-DOPA) could restore motor function by compensating for dopamine loss in the basal ganglia. This strategy was subsequently supported by evidence showing reduced activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), an iron-dependent enzyme responsible for initiating dopamine synthesis. Early biochemical studies demonstrated that iron strongly stimulates TH activity.

These insights prompted early clinical experiments with iron supplementation. Reports published during the 1980s described substantial symptom improvement in Parkinson’s patients receiving iron therapy. Some were able to reduce or discontinue dopaminergic medications. Although these studies lacked modern trial design, they raised the possibility that iron deficiency, rather than excess, could limit dopamine production in those with the disease.

The iron toxicity hypothesis

Despite early hints that iron might be beneficial, there was a marked shift toward an iron overload hypothesis as imaging and histological studies revealed increased iron signals in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. These findings, combined with growing interest in oxidative stress and ferroptosis, strengthened the belief that excess iron was toxic and should be removed.

However, the lack of benefit and potential harm observed in iron chelation trials directly challenge this model. If iron overload were truly driving Parkinson’s, removing iron should have improved outcomes. Instead, worsening symptoms suggest that iron removal may deprive already vulnerable neurons of the iron they need for survival and function, particularly at earlier disease stages.

Apparent iron overload could be misleading

A key insight of this perspective is that not all iron is biologically equivalent. Ferric iron (Fe3+), which is relatively inert, is more readily detected by MRI and histological techniques because it is stored in dense forms such as ferritin and neuromelanin. In contrast, Fe2+ is the active form required for enzymatic reactions, dopamine synthesis, and mitochondrial respiration.

MRI cannot distinguish between Fe3+ and Fe2+, nor can it identify which cell types or subcellular compartments contain iron. As a result, increased MRI iron signals may reflect sequestration of unusable Fe3+ rather than a surplus of functional iron. Similar patterns occur during chronic inflammation, where iron is sequestered into storage forms, leading to cellular iron starvation despite elevated tissue iron levels.

Additional mechanisms may worsen this problem in Parkinson’s disease, including lysosomal dysfunction that prevents iron release into the cytoplasm and sequestration of iron within glial cells rather than dopaminergic neurons. Together, these processes could create the illusion of iron overload while neurons themselves experience iron deprivation.

Support for low-iron bioavailability

Several lines of evidence strengthen the functional iron deficiency hypothesis. Disorders such as manganism resemble Parkinson’s disease and disrupt iron handling, reducing the activity of iron-dependent enzymes like TH and mitochondrial aconitase. Similarly, genetic conditions grouped under NBIA exhibit iron buildup, impaired iron utilization, and dopaminergic dysfunction.

Experimental studies provide more direct support. Deleting the transferrin receptor in mouse dopaminergic neurons causes iron deficiency, neuron loss, and Parkinson-like motor symptoms. Epidemiological data also link anemia and recent blood donation to increased Parkinson’s risk, although these associations are observational and cannot establish causality.

Implications for future therapy

Taken together, the evidence challenges the idea that iron overload is a primary driver of Parkinson’s disease. Instead, many findings are better explained by a model of functional iron deficiency, where iron is present but biologically inaccessible. This framework explains why iron chelation can worsen symptoms and why restoring iron bioavailability, rather than indiscriminately removing iron, may warrant further investigation, while accounting for disease stage and prior dopaminergic treatment.

Journal reference:

- Peikon, I., Andrews, N.C. (2026). Isn’t it ironic? Functional iron deficiency at the core of Parkinson’s disease pathobiology. Journal of Clinical Investigation. DOI: 10.1172/JCI202244, https://www.jci.org/articles/view/202244