What are functional peptides?

How spices contain functional peptides

Antioxidant activities

Anti-inflammatory potential

Enzyme inhibition and metabolic actions

Spices of interest

Food processing and peptide availability

Limitations and research gaps

References

Further reading

This article examines how culinary spices contain protein-derived bioactive peptides that emerge through processing and digestion, expanding functional food science beyond phytochemicals. Drawing on proteomic, biochemical, and extract-based evidence, it critically evaluates antioxidant, enzyme-inhibitory, and signaling-related activities while highlighting current limitations and research gaps.

Image Credit: cazawi / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: cazawi / Shutterstock.com

What are functional peptides?

Conventional pharmacological studies on spices have traditionally focused on secondary metabolites like polyphenols, alkaloids, and terpenes. More recently, food science research has also examined spice proteins and their enzymatic hydrolysates, using proteomic methods such as liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to identify short bioactive peptide sequences released from larger precursor proteins.6

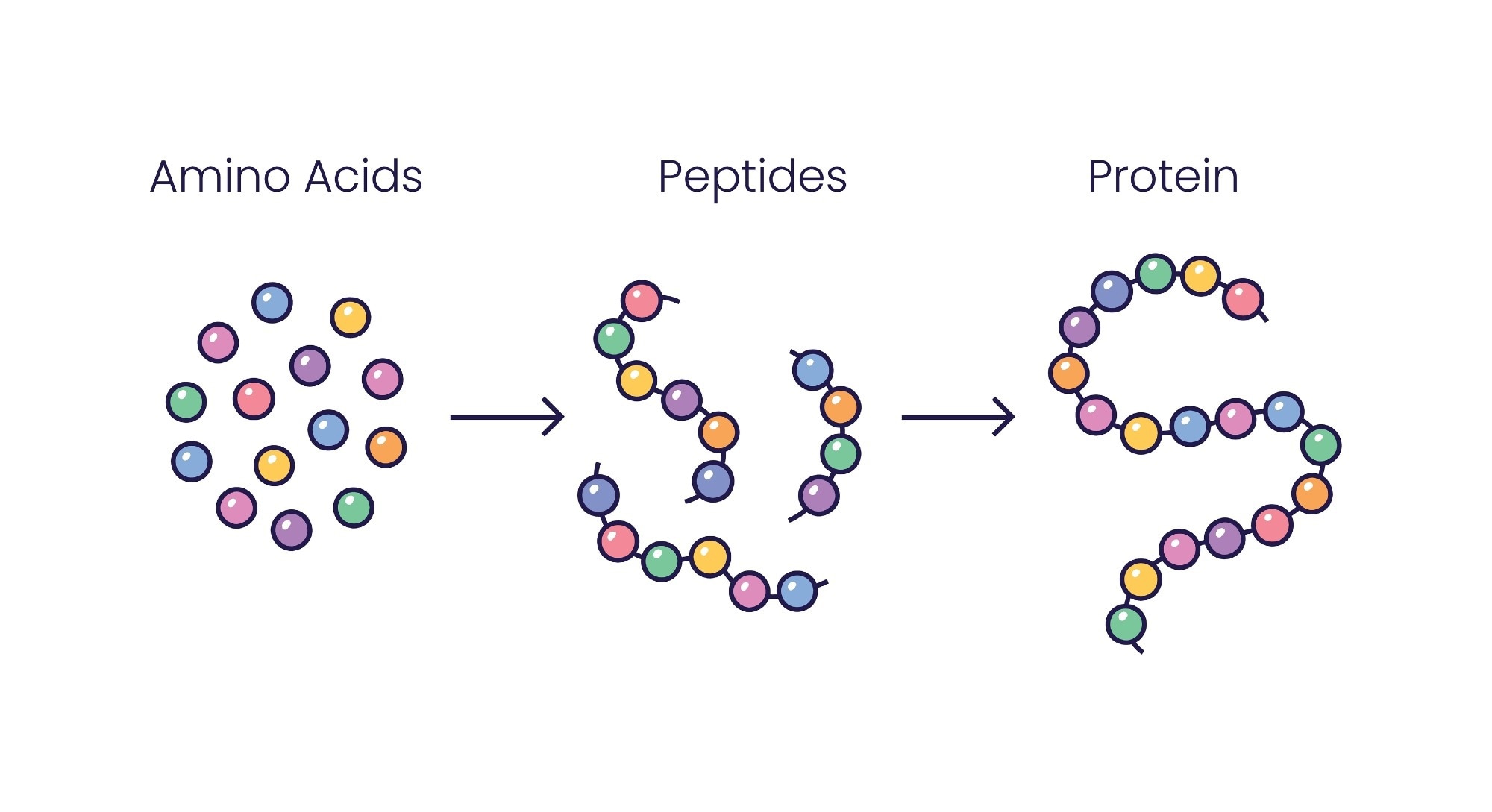

Once released during food processing, fermentation, or gastrointestinal digestion, these functional peptides can act as metabolic regulators, antimicrobials, or antioxidants.1 Functional peptides refer to specific protein fragments that, once released from their parent proteins, exert biological activities.1,2 In the context of foods, these activities are most often demonstrated using in vitro biochemical or cell-based assays, and their physiological relevance depends on bioavailability and dose.2

Unlike intact proteins, which can have the potential to be allergenic or difficult to absorb due to their complex tertiary structures, functional peptides may exhibit improved bioaccessibility, and some small peptides can cross the intestinal epithelial barrier via peptide transport systems. However, absorption efficiency varies substantially by peptide sequence and digestive conditions.6

Nutriomics and mechanistic investigations have established that the bioactivity of a peptide is dictated by its physicochemical properties, particularly its amino acid composition, molecular weight, and net charge. For example, the presence of hydrophobic amino acids like proline, leucine, and valine often correlates with high antioxidant and enzyme-inhibitory activity.2,3

Smaller peptides, typically those less than three kilodaltons (kDa) in size, exhibit greater stability against proteolytic degradation in the gastrointestinal tract.3 Moreover, cationic peptides are particularly effective as antimicrobial agents through their electrostatic interactions with bacterial membranes.3

Image Credit: LDarin / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: LDarin / Shutterstock.com

How spices contain functional peptides

Legumes and dairy have served as traditional sources of bioactive peptides. However, growing evidence suggests that many culinary spices also contain protein precursors capable of yielding functional peptides following enzymatic hydrolysis.1,2

For example, pepper seeds (Capsicum spp.), which are often discarded during processing, contain approximately 28.33% protein by dry weight, while saffron petals contain approximately 21.7% protein.1 In their raw form, these proteins are biologically inactive, with bioactivity arising after hydrolysis by enzymes such as pepsin, trypsin, or alcalase.1

The release of these peptides is strongly influenced by processing method. For instance, fermentation, aging (e.g., black garlic production), and enzymatic treatments can promote protein breakdown, while high-temperature boiling may denature proteins and reduce peptide yield. Cooking methodologies therefore significantly alter the protein and peptide profile of spices.2

Antioxidant activities

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between free radical production and antioxidant defenses, is an established risk factor for chronic disease.1,3 Although many spice extracts are recognized antioxidants, specific peptide fractions derived from edible rhizomes have also demonstrated antioxidant activity in controlled laboratory assays.6

Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

Proteolytic digestion of turmeric rhizome proteins has been shown to yield short peptides with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity, and some identified sequences also display antioxidant properties in radical-scavenging assays.6

Separate comparative studies have demonstrated that solvent-derived protein-containing fractions from clove and ginger can protect DNA from oxidative damage in cell-free experimental systems.5

At present, the majority of evidence supporting antioxidant peptide activity in spices is derived from in vitro experiments, and further work is required to establish relevance in human dietary contexts.2

Anti-inflammatory potential

In parallel with food-focused research, certain spice-related peptides are being explored in biomedical studies for their effects on cell signaling pathways, including apoptosis and angiogenesis. This work is largely pharmacological in nature and distinct from dietary intake studies.3

For example, the CRT2 peptide has been evaluated in colorectal cancer (HCT-116) cell models, where it inhibited VEGFR1-associated signaling and induced apoptosis in vitro.3

Recent functional characterization has demonstrated that peptides and other spice-derived constituents can influence enzymes involved in metabolic syndrome, particularly hypertension and type 2 diabetes (T2D).2,6

In vitro screening studies of culinary spice extracts (rather than purified peptides) have shown inhibition of α-amylase, an enzyme responsible for starch digestion, for preparations derived from cinnamon, clove, cumin, fenugreek, and nutmeg.7

Image Credit: ioancepoai / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: ioancepoai / Shutterstock.com

Spices of interest

Black pepper

Black pepper is widely studied for antimicrobial and antioxidant effects primarily attributed to phytochemicals, and it is also considered a potential source of proteins that could yield bioactive peptides following hydrolysis.2

Cloves

Comparative in vitro studies consistently rank clove among the most potent spices for antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, likely reflecting its high phytochemical and protein-associated bioactivity.5

Cinnamon

Cinnamon extracts are among those shown to inhibit carbohydrate-digesting enzymes in vitro, supporting interest in their role in postprandial glucose modulation.7

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Garlic is extensively reviewed as a functional food ingredient, with emphasis on antioxidant, antimicrobial, and processing-dependent bioactivity, including ongoing efforts to optimize extraction and preserve functional compounds in food systems.2

Food processing and peptide availability

The processing method is a critical determinant of peptide release and bioavailability.

Because many bioactive peptides are “encrypted” within precursor proteins, their release depends on hydrolysis conditions such as enzyme specificity, temperature, pH, and duration. Consequently, studies frequently combine simulated digestion, LC-MS/MS identification, and functional assays to assess peptide activity.6

More broadly, both conventional and nonconventional processing technologies can alter protein solubility and structure, influencing whether peptide-yielding substrates are preserved or denatured during food manufacturing.4

Limitations and research gaps

Despite growing interest in functional peptides from spices, several limitations remain. Most available evidence is derived from in vitro assays, with limited data on human bioavailability, metabolism, and clinical efficacy. Additionally, only a small subset of spices has been examined using peptide-level proteomic identification.2,6

Future research should integrate standardized digestion models, quantitative proteomics, and well-designed human studies to clarify the nutritional relevance of spice-derived peptides and their contribution to functional food development.

References

- Zhang, D., Ahlivia, E. B., Bruce, B. B., et al. (2025). The Road to Re-Use of Spice By-Products: Exploring Their Bioactive Compounds and Significance in Active Packaging. Foods 14(14); 2445. DOI: 10.3390/foods14142445. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/14/14/2445

- Al-Habsi, N., Al-Khalili, M., Haque, S. A., et al. (2025). Herbs and spices as functional food ingredients: A comprehensive review of their therapeutic properties, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, and applications in food preservation. Journal of Functional Foods 129; 106882. DOI: 10.1016/j.jff.2025.106882. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464625002245

- Chidike Ezeorba, T. P., Ezugwu, A. L., Chukwuma, I. F., et al. (2024). Health-promoting properties of bioactive proteins and peptides of garlic (Allium sativum). Food Chemistry 435; 137632. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137632. http://www.bdpsjournal.org/index.php/bjp/article/view/1041

- da Sailva Carvalho, C., Ojoli, G. X., Paco, M. G., et al. (2025). The Role of Nonconventional Technologies in the Extraction Enhancement and Technofunctionality of Alternative Proteins from Sustainable Sources. Foods 14(21) 3612. DOI: 10.3390/foods14213612. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/14/21/3612

- Bhattacharya, E., Pal, U., Dutta, R., et al. (2021). Antioxidant, antimicrobial and DNA damage protecting potential of hot taste spices: a comparative approach to validate their utilization as functional foods. Journal of Food Science and Technology 59(3); 1173-1184. DOI: 10.1007/s13197-021-05122-4. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13197-021-05122-4

- Sompinit, K., Lersiripong, S., Reamtong, O., et al. (2020). In vitro study on novel bioactive peptides with antioxidant and antihypertensive properties from edible rhizomes. LWT 134; 110227. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110227. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0023643820312160

- Bhosale H, Pornima G., Tukaram K., & Baisthakur P. (2019). In vitro anti-amylase activity of some Indian dietary spices. Journal of Applied Biology & Biotechnology 7(4); 70-74. DOI: 10.7324/jabb.2019.704011. https://jabonline.in/abstract.php?article_id=388&sts=2

- Naeem, B., Shams, S., Ma, L., et al. (2025). An optimized regeneration protocol for chili peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) through genotype-specific explant and growth regulator combinations. Seed Biology 4(1). DOI: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0012. https://www.maxapress.com/article/id/68994097fa6c583d6d508aa2

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 5, 2026